peter gold

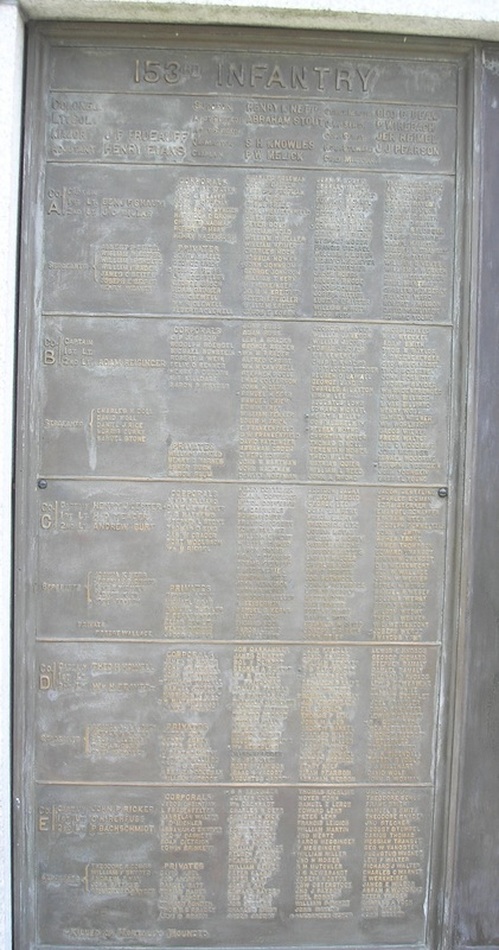

153rd pennsylvania infaNTRY

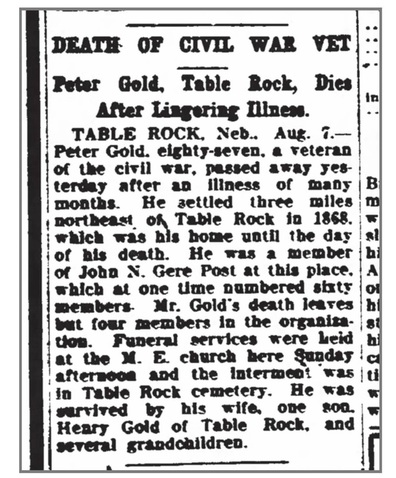

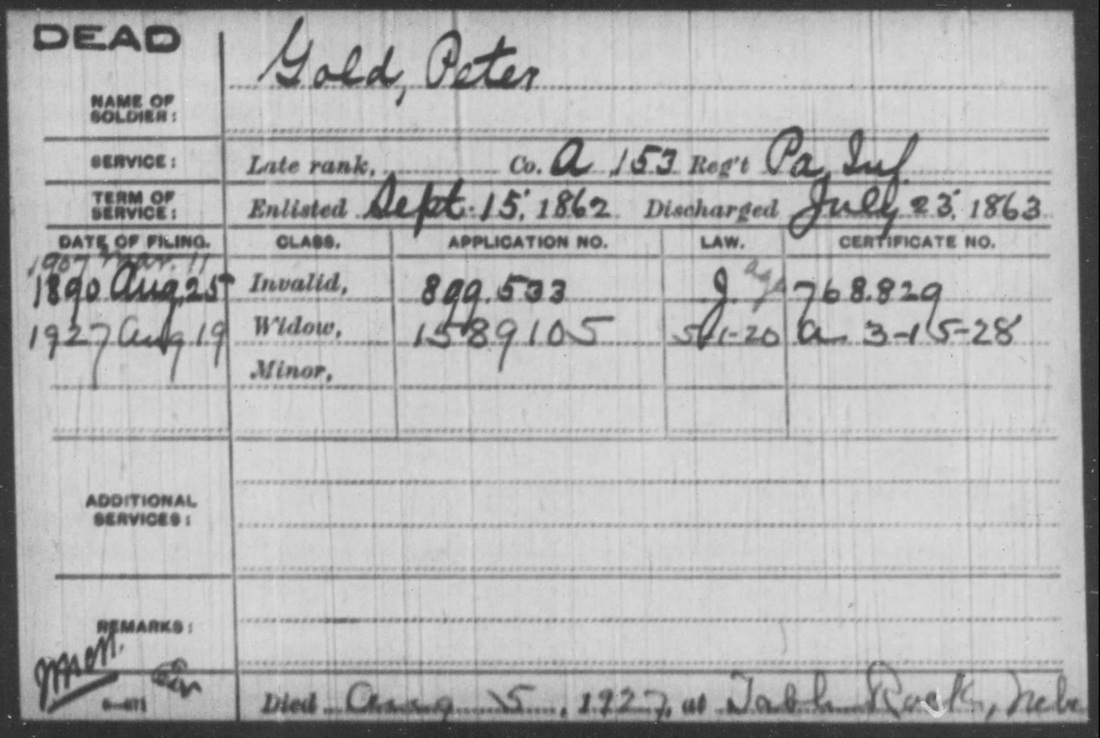

Peter's parents were Jacob and Eva Gold. They were older parents, having been on the edge of 40 when he was born. He had at least two older brothers, Hiram (who became a medical doctor) and George. He had an older sister and a younger sister, Ebesina and Emma. He was 22 when he enlisted in 1862. Between his enlistment in October 7, 1862 and his mustering out on July 23, 1863, with the rest of the regiment, he saw "just" two battles, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

CHANCELLORSVILLE

APRIL 30 - MAY 6, 1863

MAY 3, 1863 - THE SECOND BLOODIEST DAY OF THE WAR (the bloodiest was a day at antietam)

lee's greatest victory

CHANCELLORSVILLE - The very name produces powerfully evocative images known to even the most novice of Civil War buffs...Lee and Jackson at their last meeting, Confederates pushing down the Plank Road towards an overly exposed Union Eleventh Corps, the cannons exploding with death from Hazel Grove, a large mansion ablaze at the intersection of the Orange Plank and Ely's Ford Road, fire around the pulpit of the Salem Church. The list could go on and on.....The fighting that took place during the Chancellorsville Campaign was wide-spread and complicated. Peter Gold was there. He was in Company A of the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry. The 153rd found themselves on the front line of a famous battle maneuver by Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. They remain in the middle a historical controversy involving the "Eleventh Corps," which included the 153rd.

|

chancellorsville --- made famous by the "audacious" maneuvers of generals robert e. lee & stonewall jackson

The Union troops were headed by General Joseph Hooker, now famous for his indecision and lack of judgment at critical moments. He was eventually replaced but at the time of Chancellorsville his flaws had not yet been appreciated. Hooker was sent after rebel troops holding the Chancellorsville crossroads, led by Lee.

On Day One, Hooker brought his troops across the Rapahannock River in an adroit fashion. Hooker had twice as many troops as his opponent, Hooker and his officers were well pleased with the situation. Then things went, as they say.

The next day, Hooker began to move his troops out of the Wilderness to ground that was more open so that he could fully employ his strength. Before he could get his men clear of the woods, though, General Jackson’s soldiers plowed into them on the Orange Turnpike. Split up contrary to longstanding principals of war, Jackson’s troops also appeared on the Union right flank. There was a "sharp, brief" battle and Hooker ordered a general retreat.

That night, Lee and Jackson "met at a bivouac in the woods and devised one of the boldest actions of the entire Civil War. Jackson, with almost 30,000 men and 110 cannon, would march 12 miles and fall upon the Federal army’s right flank. During this maneuver, Jackson’s force would be isolated from the rest of Lee’s army. If Hooker’s army became aware of this division, Lee’s forces could face great peril. In hindsight, we know that Jackson’s secret flank march was a tremendous success for the Confederates, but at the time it was a high stakes gamble that depended upon subterfuge and bluff."

Jackson's target: the Union Eleventh Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, which was holding the far right of the Union position at Chancellorsville.

In the face of Stonewall Jackson's successful surprise attack, the men of the 153rd "left" the area. At the time, they were derided as the "Flying Dutchmen," a reference to the heavy Pennsylvania Dutch presence in the 11th Corps, men including Peter Gold. History seems to have since vindicated them, recognizing the untenable battle position in which the inattentive General Hooker had placed them.

On Day One, Hooker brought his troops across the Rapahannock River in an adroit fashion. Hooker had twice as many troops as his opponent, Hooker and his officers were well pleased with the situation. Then things went, as they say.

The next day, Hooker began to move his troops out of the Wilderness to ground that was more open so that he could fully employ his strength. Before he could get his men clear of the woods, though, General Jackson’s soldiers plowed into them on the Orange Turnpike. Split up contrary to longstanding principals of war, Jackson’s troops also appeared on the Union right flank. There was a "sharp, brief" battle and Hooker ordered a general retreat.

That night, Lee and Jackson "met at a bivouac in the woods and devised one of the boldest actions of the entire Civil War. Jackson, with almost 30,000 men and 110 cannon, would march 12 miles and fall upon the Federal army’s right flank. During this maneuver, Jackson’s force would be isolated from the rest of Lee’s army. If Hooker’s army became aware of this division, Lee’s forces could face great peril. In hindsight, we know that Jackson’s secret flank march was a tremendous success for the Confederates, but at the time it was a high stakes gamble that depended upon subterfuge and bluff."

Jackson's target: the Union Eleventh Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, which was holding the far right of the Union position at Chancellorsville.

In the face of Stonewall Jackson's successful surprise attack, the men of the 153rd "left" the area. At the time, they were derided as the "Flying Dutchmen," a reference to the heavy Pennsylvania Dutch presence in the 11th Corps, men including Peter Gold. History seems to have since vindicated them, recognizing the untenable battle position in which the inattentive General Hooker had placed them.

The 153rd -- OUTFLANKED BY STONEWALL JACKSON

COMPANY A -- PETER GOLD'S COMPANY -- IS THE FIRST TO FIND OUT

"A large body of the enemy amassing in my front. For God's sake make dispositions to receive them."

|

Will Schielhing of the Morning Call writes about the 153rd. In describing Jackson's surprise attack, he cites Company A -- Peter Gold's company, comprised of about 100 men.

|

Six months after leaving [home], the men of the 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteers finally found themselves in a line of battle on the afternoon of May 2, 1863. |

The men fell back. One historian pointed out that the brand of coward was unfair and unrealistic:

[T]he routed Eleventh Corps became a convenient scapegoat for the overall defeat at Chancellorsville. But as noted Civil War historian Bob Krick highlights, “No corps in the army—or any army—could have stood up to the might of [Jackson’s] attack, combined as it was with overwhelming surprise, and coming from the worst possible tangent relative to their positions. They did not deserve calumny for the result…”

The 153rd arrived at the Chancellorsville battle ground on the evening of April 30 and was posted along the Old Turnpike.

The night was quiet, and the weary troops slept soundly.

At mid-day of the 1st, the enemy attacked away to the left of the line, and the brigade was ordered to move to its support. This order was soon countermanded, but was again renewed, and until near midnight the brigade was kept in motion for threatened points. It then returned to its old position on the right, where, during the forenoon of the 2d, it was engaged in erecting barricades, throwing up rifle-pits, and felling the timber in front.

The First Division held the right of the corps, and the First Brigade the right of the division. The Forty-first, and Forty-fifth New York, were upon the general line of the corps, south of the Old Turnpike. Upon the right of the Forty-fifth were two pieces of artillery commanding the turnpike. The One Hundred and Fifty-third Pennsylvania, and the Fifty-fourth New York, were north of the pike, upon a line refused, and nearly at right angles with the pike, forming the extreme right of the line of the army.

The One Hundred and Fifty-third was disposed more as a close line of skirmishers, than as a regular line of battle, the men being ordered to stand three feet apart, its left resting on the turnpike, the line extending through the wood and across a road leading into the turnpike, its right supported by the Fifty-fourth New York.

When the rebel leaders came out from Fredericksburg, and found Hooker well posted about the Chancellor House, they despaired of routing him by direct attack. Lee accordingly determined to send Jackson, with all his corps, comprising two-thirds of the entire rebel army, by a circuitous route by the front of the Union army, to its extreme right and rear, and strike it unawares with this overwhelming force.

Taking byroads, and screening his movements by clouds of cavalry, that hovered upon his right flank, Lee, in the meantime, keeping up a noisy demonstration along the Union front looking towards Fredericksburg, the daring leader brought his men to the point desired, without having his purposes disclosed to the Union commanders. The movement of this heavy column with all its trains, past the front, was observed at various points, but a strange infatuation seemed to have seized the Union commanders, that their fine strategic move in crossing the river, and gaining the rear of the rebel army unopposed, had intimidated the rebel leader, and that he was now in full retreat. General Howard says, in his official report: "I should have stated that just at evening of May 1st, the enemy made a reconnoissance on our front, with a small force of artillery and infantry. General Schimmelfennig moved out with a battalion, and drove him back."

During Saturday, the 2d, the same General made frequent reconnoissances. Infantry scouts and cavalry patrols were constantly pushed out on every road." The unvarying 3 report was,'" The enemy is crossing the plank-road and moving towards Culpepper."

At one o'clock P. M., of the 2d, three shots were fired by the enemy, which were answered by a tremendous volley from the brigade line, thus disclosing its position and strength. A party of skirmishers was at once thrown out, under command of Captain Owen Rice [Company A], and precautions taken against a surprise. At a little before five o'clock, the skirmishers were driven in, and before they had reached the line of battle, the enemy's bugles sounded the charge, and in three lines, with powerful supports, supplied with artillery, he broke like a whirlwind upon the feeble and attenuated line of Von Gilsa's Brigade.

The One Hundred and Fifty-third was first struck. This was its first experience of battle; but with the steadiness of veterans, a volley was poured in with deadly effect. The two pieces of artillery immediately started to the rear, and with them went the troops in support on their left. The enemy was coming in on both flanks; to stand longer was certain destruction, and accordingly, Colonel Von Gilsa gave the order to retire. "Our backward moveihent," says an officer of the regiment, " was begun just in season. Had we remained a minute longer, all would doubtless have been captured. The enemy had not only outflanked us on our extreme right, but were also advancing in force on our immediate left." Broken and disorganized by this overwhelming blow, the fragments of the brigade retired rapidly, little opportunity being given to re-fbrm, until they reached the open ground to the west of Chancellorsville. Here the regiment was rallied, and a position assigned it for the night.

A fatigue detail of fifty men was given, who, in conjunction with similar parties, were sent to bury the dead, remove the wounded, and construct breast-works. These were kept busily employed until two o'clock on the morning of the 3d. At three o'clock the regiment was aroused, and with the division, went into breast-works on the left centre of a new and more contracted line, looking eastward, and covering the United States Ford Road.

Colonel Glanz having fallen into the enemy's hands, and Lieutenant Colonel Dachrodt having been wounded, the command devolved upon Major Frueauff, who was relieved for that purpose, at his own request, from service on the staff of General Devens.

At ten A. M., the firing in front opened. A heavy line of skirmishers was at once thrown out to meet the advancing enemy, and the main line was speedily strengthened, under the supervision of Colonel Von Gilsa. Sharp-shooting and a heavy cannonade was kept up during the entire day, but, fortunately, with little loss to the regiment. It was renewed on the following morning, but the division continued to hold its position until the night of the 5th, when, with the army, it withdrew, and returned to its camp at Potomac Creek Bridge. The loss in the entire battle was nineteen men killed, three officers, and fifty-three men wounded, and thirty-three prisoners.

Having survived Chancellorsville -- where there were over 40,000 casualties -- Peter Gold marched with the 153rd from Virginia back to his native Pennsylvania. Within a few months, things got even worse, at Gettysburg, where almost 50,000 casualties were sustained by both sides in three days of battle.

gettysburg

July 1 - 3, 1863

The bloodiest battle of the civil war

|

Other Gettysburg survivors who ended up in Table Rock included Captain Richard P. Jennings, a Confederate with the 23rd Virginia Infantry. Two other men went to the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion, although their role seems unclear: confederate William T. Shorter, and Union soldiers John C. Smith.

|

Until the opening of the summer campaign northward, few changes occurred, and the regiment was engaged in the usual camp duties. On the afternoon of the 12th of June, with three days' rations, and sixty rounds of ammunition per man, the march towards Pennsylvania was commenced. ...The corps arrived at Emmittsburg on the 30th of June. At eight o'clock on the following morning, it was put in motion towards Gettysburg, moving at a rapid rate to the sound of the enemy's guns, and passing through the town at half-past one.

At the Poor House, north of the town, the brigade halted and deposited knapsacks, and was then ordered to advance at double-quick, and dislodge the enemy from a piece of woods to the right of the line taken up by the Eleventh Corps. Gallantly did the brigade advance, and cleared the intervening ground; but the enemy was already in heavy force, advancing on all sides, the brigades of Hayes and Hoke, in double line, in its immediate front, and infantry and artillery, most advantageously posted, away to the right and flank of its position. It was losing fearfully, and had no hope of gaining any advantage, when Colonel Von Gilsa, unwilling to sacrifice his men needlessly, ordered them back. In this brief engagement, the regiment lost one officer, and thirty two men killed, eight officers, and ninety-three men wounded, and eighty-two missing and prisoners.

The corps was soon afterwards ordered to retreat through the town, and take position on Cemetery Hill. Von Gilsa's Brigade went into position to the right of the Baltimore Pike, behind a low stone-wall, nearly opposite the Cemetery gate, and in front of batteries F, and G, of the First Pennsylvania Artillery. Content with his victory, the rebel leader neglected to follow up his advantage, and the exhausted troops slept undisturbed.

During the 2d, the artillery fire bearing upon the centre was very severe, but little loss was sustained until four in the afternoon, when a perfect storm of shot and shell was poured upon it, inflicting merciless slaughter, men on every hand writhing in the agonies of death.

Towards evening it was discovered that the enemy was moving for a demonstration upon the right flank, and a change of front to meet him was made. Scarcely had the change been effected, when a powerful column of the enemy, which had secretly formed under cover of a rising ground, consisting of the brigades of Hayes and Hoke, burst upon the view, and charged full upon the position occupied by Von Gilsa.

Shot and shell were poured into them from the artillery crowning the hill, and showers of bullets from the well poised muskets of the infantry; but unheeding the fall of comrades, they rushed on undismayed, crossed the low stone-wall, and were among the guns.

It was no longer a question of steady aim or effective missiles, but a hand-to-hand encounter, in -which clubs and stones were freely used. "

At one time," says the officer above quoted, "defeat seemed inevitable. Closely pushed by the enemy, we were compelled to retire on our first line of defenses, but even here the enemy followed us, while the more daring were already within our lines, and were now resolutely advancing towards our pieces.

The foremost one had already reached a piece, when, throwing himself over the muzzle of the cannon, he called out to the bystanding gunners: "I take command of this gun.''

"Din sollst sie haben," was the curt reply of the sturdy German, who, at that very moment, was in the act of firing. A second later, and the soul of the daring rebel had taken its flight." With a desperate persistence, the enemy struggled for the mastery; but all in vain. His bravest had fallen. The Union lines were being rapidly reinforced, and seeing no hope of holding the ground, he sullenly retired.

During the following day, the position was subjected to a fierce artillery fire, but the enemy made no more attempts with his infantry upon that part of the line.

At six o'clock on the morning of the 4th, unusual movements of the enemy having been observed, a detachment of seventy-five men, forty-six of whom were from the One Hundred and Fifty-third, under Lieutenant Bachschmid, was sent out towards the town to discover the rebel strength. They were soon greeted by hostile shots, but pushing forward, they captured two hundred and ninety prisoners, and two hundred and fifty stands of arms, and found that the main body of the rebels had gone.

The loss in the entire battle was one officer, Lieutenant William H. Beaver, and ten men killed, eight officers, and one hundred and eight men wounded, and one hundred and eighty-eight missing; an aggregate of three hundred and eight.

With the battle of Gettysburg, ended the hard fighting of the regiment; but hard marching was still in store for it. When arrived at Emmittsburg, whither the regiment was led in pursuit of the retreating rebel column, the term of service of six of the companies had expired, and they asked for their release; but their request was not granted, and the command continued to move with the corps until it came up with the rebel column, in the of Funkstown, where skirmishing was in progress.

On the morning of the 14th, orders for the discharge of the regiment having been received from Washington, it moved by Frederick City and Baltimore, to Harrisburg, where, on the 24th, the regiment was mustered out of service. On the following day, it returned in a body to Easton, where an enthusiastic public reception was accorded it, and it was finally disbanded. On taking leave of the regiment, upon its departure from his brigade, Colonel Von Gilsa said:

" I am an old soldier, but never did I know soldiers, who, with greater alacrity and more good will, endeavored to fulfill their duties. In the battle of Chancellorsville you, like veterans, stood your ground against fearful odds, and, although surrounded on three sides, you did not retreat until by me commanded to do so. In the three days' battle at Gettysburg, your behavior put many an old soldier to the blush, and you are justly entitled to a great share of the glory which my brigade has won for itself, by repulsing the two dreaded Tiger Brigades of Jackson. In the name of your comrades of the First Brigade, and myself, I now bid you farewell."

__________________________

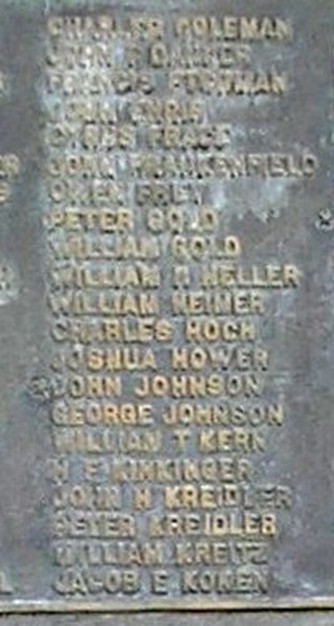

proof that peter gold was there.....

Regimental histories rarely mention the names of enlisted men, and the history of the 153rd is typical. However, the monument to the men of Pennsylvania 153rd leaves no doubt that Peter Gold was in that battle. This monument has bronze plaques bearing the names of the Pennsylvanians in the battle, regiment by regiment. There, with the men of the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry, and in the list of the men of Company A, is the name of Peter Gold.

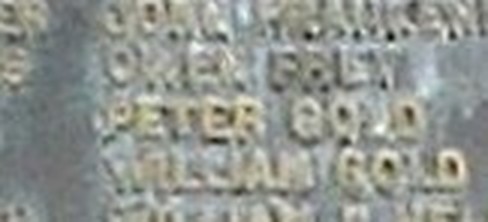

Look for Peter Gold's name:

Look more closely -- it's there...

peter was one of four gold men in the 153rd

The entire regiment of the 153rd Pennsylvania came from the same county in eastern Pennsylvania, Northampton County. There were four Golds in the regiment -- Peter, William, and Lewis were in Company A, and Richard in Company K. There were a number of Gold families in the county and it is unclear how Peter was related to the others other than that they were not brothers.

The men of the 153rd saw "just" two battles during their period of service. At Gettysburg, on the second day, William Gold was killed and Richard wounded.

The men of the 153rd saw "just" two battles during their period of service. At Gettysburg, on the second day, William Gold was killed and Richard wounded.