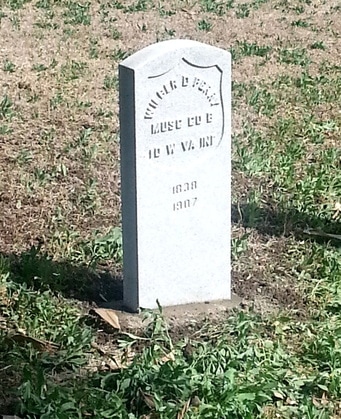

the story of

wilber d. perry

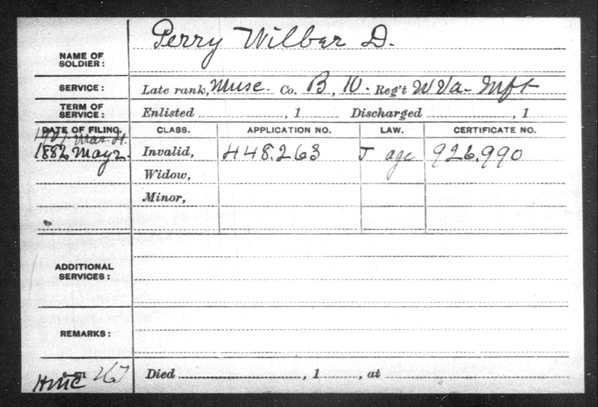

MUSICIAN, Company B, 10th West Virginia Infantry

MUSTERED IN OCTOBER 4, 1862, MUSTERED OUT MAY 22, 1865

AND THE 2016 CEREMONY

DEDICATING HIS MILITARY TOMBSTONE

AN UNMARKED GRAVE NO MORE

A little background

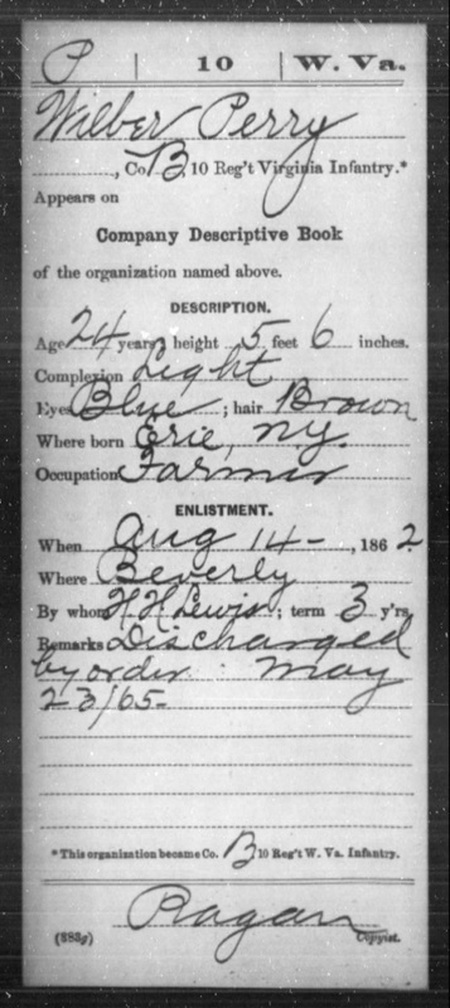

W. D. Perry. He used the initials W.D., so his first name has been little known. His name was Wilber Devello Perry.

Family genealogist Dave Etherton shared some information about W.D., and provided the information that W. D. was in the 10th West Virginia Infantry. W. D. was the great great grandfather of Dave's wife.

Dave related that W. D. was the descendant of some of the earliest English settlers. Six generations before W.D. , Edmund Perry was born in Bridford, England in 1588; he died in America in 1641 in Sandwich, Massachusetts. W. D.'s own parents, Elias and Adelia Phillips, were born in New England in the early 1800s and ended up in West Virginia. His father died years before the Civil War, his mother right after.

W. D. was probably born in New York but his family eventually moved to Upshur County, West Virginia. He was there when in 1862 he enlisted in the 10th West Virginia Infantry at about age 21.

Family genealogist Dave Etherton shared some information about W.D., and provided the information that W. D. was in the 10th West Virginia Infantry. W. D. was the great great grandfather of Dave's wife.

Dave related that W. D. was the descendant of some of the earliest English settlers. Six generations before W.D. , Edmund Perry was born in Bridford, England in 1588; he died in America in 1641 in Sandwich, Massachusetts. W. D.'s own parents, Elias and Adelia Phillips, were born in New England in the early 1800s and ended up in West Virginia. His father died years before the Civil War, his mother right after.

W. D. was probably born in New York but his family eventually moved to Upshur County, West Virginia. He was there when in 1862 he enlisted in the 10th West Virginia Infantry at about age 21.

w. d. perry and the civil war

LATE 1861 TO FALL 1864

W. D. Perry was a musician in Company B of the 10th West Virginia Infantry. According to Mara Blake, a great great granddaughter, Wilber's son Ollie reported that he was a drummer.

Company B was organized in Upshur County by a Colonel Harris and in December 1861 had only 90 men. They were armed with “45 of the old smooth bore muskets” and Colonel Harris asked for rifles to be sent “immediately.” Another company was raised for he regiment but it had only “40 guns and with almost no clothing.” They were sent out with the expectation of more guns, which did not come. It was not until June of 1863 that the poorly-armed men were issued weapons of any significance and it was then 58-caliber Enfield rifles.

The 10th was early on kept in West Virginia fighting bands of guerillas and bushwhackers and trying to hold the frontier against the confederacy with only a thin line of troops. Their attempts to protect the counties on the front lines were not always successful and they were in danger of being wiped out. Not long after they were issued Enfield rifles in June 1863, an overwhelming force of Confederates headed their way. It was the first time the entire regiment engaged the enemy as a unit.

On the day that the entire regiment was first involved in a battle as a unit, Wilber was returning from a furlough. As he and an officer approached the lines, they were captured.

The events of July 2, 1863 are narrated in a wonderful book about the 10th West Viginia The book is in the library of the University of Illinois and is called "Major General Thomas Maley Harris, a member of the military commission that tried the President Abraham Lincoln assassination conspirators, and Roster of the 10th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 1861-1865." The events of that day are described in detail, derived from sources such as the famous Dyer histories.

Company B was organized in Upshur County by a Colonel Harris and in December 1861 had only 90 men. They were armed with “45 of the old smooth bore muskets” and Colonel Harris asked for rifles to be sent “immediately.” Another company was raised for he regiment but it had only “40 guns and with almost no clothing.” They were sent out with the expectation of more guns, which did not come. It was not until June of 1863 that the poorly-armed men were issued weapons of any significance and it was then 58-caliber Enfield rifles.

The 10th was early on kept in West Virginia fighting bands of guerillas and bushwhackers and trying to hold the frontier against the confederacy with only a thin line of troops. Their attempts to protect the counties on the front lines were not always successful and they were in danger of being wiped out. Not long after they were issued Enfield rifles in June 1863, an overwhelming force of Confederates headed their way. It was the first time the entire regiment engaged the enemy as a unit.

On the day that the entire regiment was first involved in a battle as a unit, Wilber was returning from a furlough. As he and an officer approached the lines, they were captured.

The events of July 2, 1863 are narrated in a wonderful book about the 10th West Viginia The book is in the library of the University of Illinois and is called "Major General Thomas Maley Harris, a member of the military commission that tried the President Abraham Lincoln assassination conspirators, and Roster of the 10th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 1861-1865." The events of that day are described in detail, derived from sources such as the famous Dyer histories.

There was little time for celebration or rest for Colonel Harris and the |

|

So Wilber was not alone. An officer and an entire group of 14 men on picket duty also fell into Confederate hands. It was just not a good day.

|

It was thought that he returned to the lines at some point, but Mara provides the information that Wilber was in Libby Prison in Richmond. With little doubt, then, when Wilber and the others were captured, off to Libby prison they went. While they were not in famous battles, they were almost surely fighting for their lives in relentlessly grim situations in Libby Prison and then in a prison in Georgia.

a prisoner of war

According to family history passed down from Wilber's son to his daughter to his daughter's granddaughter, Wilber was in Libbey prison. We know from the regimental history that he was taken prisoner closed to the unit's entry into the war in 1863. He probably spent the duration, being in prison for almost two years.

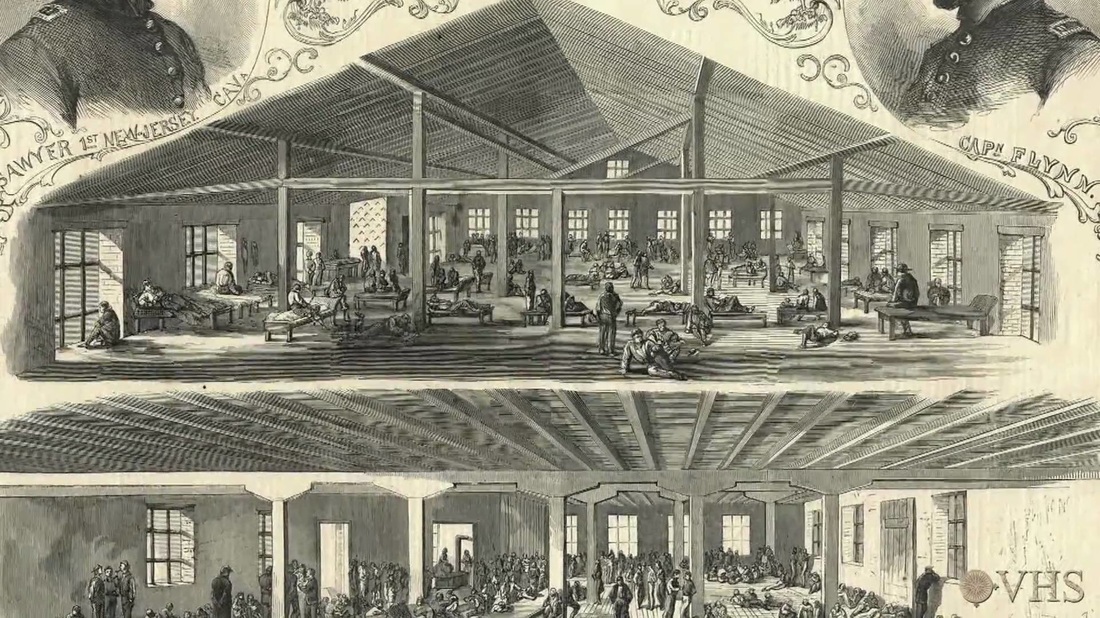

The prison is described in detail in Wikipedia (and many other places)

The prison is described in detail in Wikipedia (and many other places)

Libby Prison was a Confederate prison at Richmond, Virginia . It gained an infamous reputation for the overcrowded and harsh conditions under which officer prisoners from the Union Army were kept. Prisoners suffered from disease, malnutrition and a high mortality rate. By 1863, one thousand prisoners were crowded into large open rooms on two floors, with open, barred windows leaving them exposed to weather and temperature extremes. |

The Wikipedia article provides more details about the prison conditions:

Upon their release from Libby a group of Union surgeons published an account in 1863 of their experiences treating Libby inmates in the attached hospital:

"Thus we have over ten per cent of the whole number of prisoners held classed as sick

men, who need the most assiduous and skilful attention; yet, in the essential matter of

rations, they are receiving nothing but corn bread and sweet potatoes. Meat is no longer

furnished to any class of our prisoners except to the few officers in Libby hospital, and all

sick or well officers or privates are now furnished with a very poor article of corn

bread in place of wheat bread, unsuitable diet for hospital patients prostrated with

diarrhea, dysentery, and fever, to say nothing of the balance of startling instances of

individual suffering and horrid pictures of death from protracted sickness and semi-

starvation we have had thrust upon our observation.

They said that prisoners were always asking for more food and that many were only half clad. Newly arriving prisoners who were already ill often died quickly, even in one night. Due to the "systematic abuse, neglect and semi-starvation," the surgeons believed that thousands of men would be left "permanently broken down in their constitutions" if they survived. In one story they noted that 200 wounded prisoners brought in from the battle of Chickamauga had been given only a few hard crackers during their three days' journey, but suffered two more days in the prison without medical attention or food.

An article in the Daily Richmond Enquirer vividly described prison conditions in 1864:

"Libby takes in the captured Federals by scores, but lets none out; they are huddled up and jammed into every nook and corner; at the bathing troughs, around the cooking stoves, everywhere there is a wrangling, jostling crowd; at night the floor of every room they occupy in the building is covered, every square inch of it, by uneasy slumberers, lying side by side, and heel to head, as tightly packed as if the prison were a huge, improbable box of nocturnal sardines."

THE TRANSFER TO A PRISONER OF WAR CAMP IN MACON, GEORGIA

|

Assuming Wilber hadn't been released from Libby Prison -- an unlikely event -- he would have been included in the transfer to Macon, Georgia. The infamous Andersonville Prison, said to be the worst of the worst, was in Macon County, Georgia, but Wilber was presumably transferred to Camp Oglethorpe, which is in the town of Macon, Georgia.

|

we are indebted to the sons of confederate veterans for this unflinching descreption of camp oglethorpe: |

This POW camp had been the town's fairgrounds before the war. It, too, was, to say the least, a grim place. However, as the Sons of Confederate Veterans say, "It must be pointed out that conditions were equally as horrible at all POW camps in the north and south." It was difficult for the South to take care of even its own citizens. Macon, Georgia had no more resources than anywhere else. The Macon Daily Telegraph said, "At a time when it is difficult to feed our own population, we are to be blessed with the presence and custody of 900 prisoners of war. We have no place to hold them---no food to give them---nobody whose time can be well spared to guard them---nor, except in the mere matter of hostages for the safety of our own prisoners in Lincoln's dominions, can we conceive of any object in holding them as prisoners."

The website of Camp 1339 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans includes a description of the conditions at the camp:

The website of Camp 1339 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans includes a description of the conditions at the camp:

The following is a description of Camp Oglethorpe from "Portals to Hell."

[Speer, Lonnie R. Portals To Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Mechanicsburg. Stackpole Books, 1997.]

The facility at Macon, Georgia, officially named Camp Oglethorpe in honor of the founder of the state, James Oglethorpe, was located about a quarter mile southeast of town in the old fairgrounds. The camp consisted of fifteen to twenty acres containing a large building used as a hospital and a number of sheds and stalls, all surrounded by a highboard fence.

The enclosure, situated between a triple set of railroad tracks and Ocmulgee River, stood twelve feet high and was constructed heavy upright boards. A sentry walkway around the top was occupied heavily armed guards at twenty-pace intervals.

"The gate," reported one prisoner, "(was) spanned from post to post by a broad, towering arch, showing on its curve, in huge black letters 'Camp Oglethorpe'. We were conducted first to the office of the prison, which stood but a few feet from the gate, and there halted and detained until preparation could be made within for another examination."

The prisoners were thoroughly searched, which even included unraveling their clothing linings to locate hidden money, and were led up to gate one at a time.

"The guard pounded the boards with the butt of his gun," remembered prisoner John Hadley, "the bolt glided back, the hinges creaked, the big gate swung open and then there appeared before us a sea of ghostly, grizzly, dirty, haggard faces, staring and swaying this way and that.''

All around the inside of the enclosure, an ordinary picket fence three and a half feet high, sixteen feet out from the wall, served as the prison deadline. At the northwest corner of the stockade was a large grove of pine trees. A small stream ran through the west end. The large one-story frame building, once the floral hall for the fair, stood at the center of the enclosure and was often occupied by two hundred POWs. The remainder slept in the sheds or stalls or created their own shelter in the yard. The Macon pen held anywhere from 600 prisoners in 1862 to 1,900 in 1864.

Rations at Macon, consisting of one pint of unsifted cornmeal per day, four ounces of bacon twice a week, and enough peas for two soup dinners per week, were issued in five- or seven-day allotments and left to the POWs to manage the rations through that period. "The only fights I saw in prison," noted one Macon prisoner, "grew out of the dividing of rations, and they were not infrequent."

Roll call at Macon was conducted in a sort of herding process. "The Officer of the Day would come in each morning with twenty guards and deploy them across the north end the pen, explained one of the prisoners, "then all began whooping and hollering and swearing to drive us to the south end. This being accomplished, an interval between the guards was designated as the place for the count, which was effected by our returning, one by one, through that interval, into the body of the enclosure."

The final disposition of Camp Oglethorpe is described thusly: Camp Oglethorpe, in Macon, went on to serve as a parole site at the end of the war but was torn down sometime later.

In Folsom's book Heroes and Martyrs of Georgia he states:

"At this most laborious and disgusting service, the battalion suffered exceedingly with sickness and was not relieved until the last Federal prisoner was sent to Richmond to be exchanged."

This was apparently Wilber's life for almost two years, first at Libby Prison and then at Oglethorpe.

after the warWilber Perry was mustered out at the end of the war. He went back home and married Hester Roby. Hester’s husband had died in 1863 at age 23, probably a victim of the war. Wilber & Hester had six or seven children and also Caroline Cunningham, Hester's child from her first marriage. All were born in West Virginia.

Their oldest child, Lizzie Perry Freeman, was born in West Virginia in 1866. Lizzie's great grandson Tom Freeman lives in Table Rock. Ollie's great great granddaughter Mara Blake lives in Colorado. Hattie Perry Jones was born in 1878. Dave Sejkora and other members of the family in Burchard, Nebraska are descendants. . In 1879, Wilber & Hester brought their family to Table Rock. In 1887, a photograph of Table Rock Civil War veterans was taken. We don’t know which one is him but he is probably in there. Hester died in 1890. Her stone is in the southwest quarter of the cemetery and is moderately substantial. However, it is tilting moderately and skewed off its base. |

the search for a record of his death

Dates of birth and death are not mandatory for the military tombstone of a Civil War veteran.

We wanted those dates on the tombstone, however. The search was difficult but took a while.

We could calculate his birth year based on his reported age when he listed, but without the year he died, both dates would be eliminated.

We knew he was still in West Virginia in 1870, where he appears on the census with three children and little Caroline Cunningham; Caroline was Hester's child with her first husband, who died during the war. By the time of the 1880 census he was in Pawnee County with Hester, and six kids between the ages of 3 and 14 -- Elizabeth, Ida, Florence, Elliott, Homer, and Harriet, and Caroline Cunningham who was by then 18.

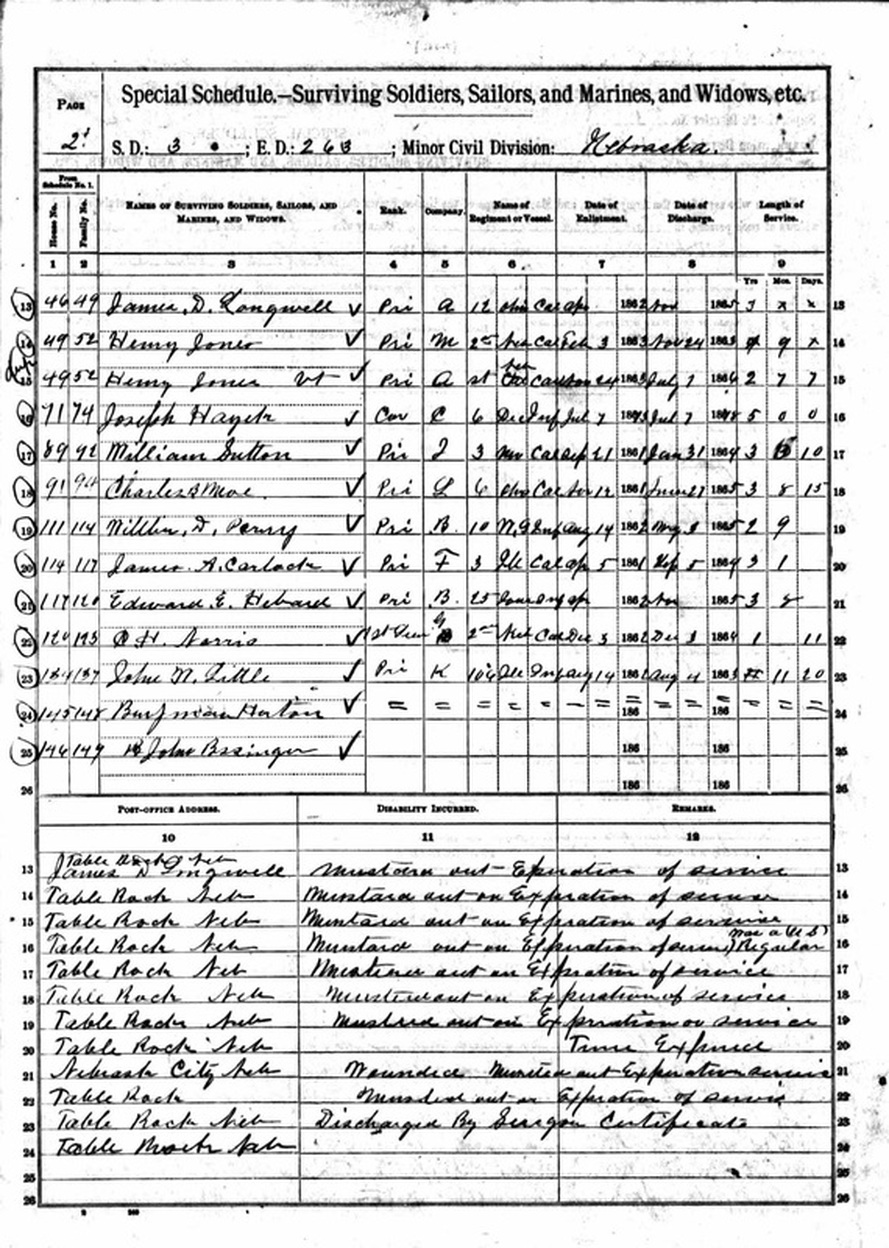

In 1880, he was also on a list of veterans living in Pawnee County. There he is, number 19, and below you can see him listed as living in Table Rock.

We wanted those dates on the tombstone, however. The search was difficult but took a while.

We could calculate his birth year based on his reported age when he listed, but without the year he died, both dates would be eliminated.

We knew he was still in West Virginia in 1870, where he appears on the census with three children and little Caroline Cunningham; Caroline was Hester's child with her first husband, who died during the war. By the time of the 1880 census he was in Pawnee County with Hester, and six kids between the ages of 3 and 14 -- Elizabeth, Ida, Florence, Elliott, Homer, and Harriet, and Caroline Cunningham who was by then 18.

In 1880, he was also on a list of veterans living in Pawnee County. There he is, number 19, and below you can see him listed as living in Table Rock.

|

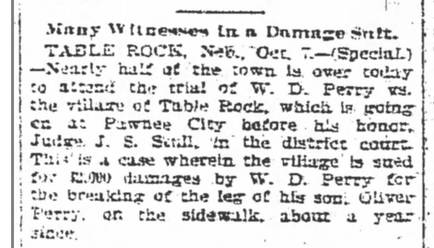

Wilber Perry was here in Table Rock 1896, when his son Oliver broke his leg on a sidewalk in Table Rock and 1897 when “half the town” attended a trial culminating a lawsuit that Perry brought against the town for his son's injuries. We don't know the result of the trial. We do note that in 1898, a vigorous program by the town to eliminate board sidewalks and require brick and similar permanent surfaces was instituted. We don't know if a board sidewalk was the cause of the fall.

|

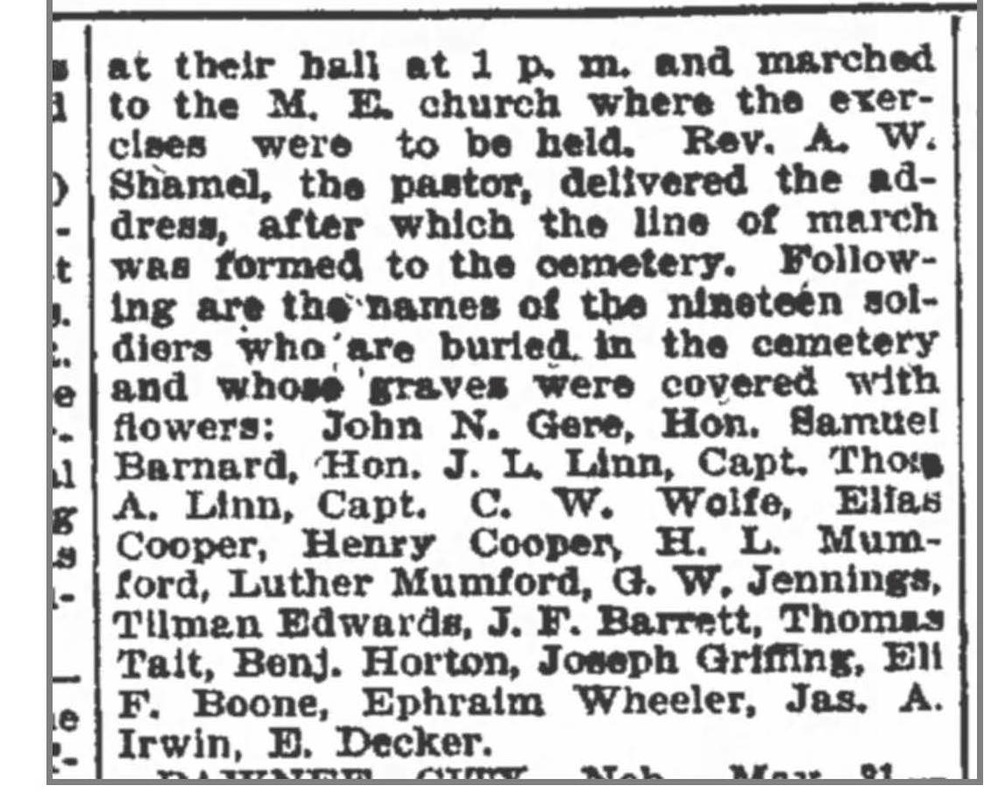

A 1901 news article about Decoration Day listed the veterans’ graves (the first few lines of which were in another column. All of the graves were covered with flowers. Wilber Perry's grave was not among those flower-heaped graves. The opening lines were in another column and have been temporarily misplaced, but here is the second portion in which the decorated graves are listed:

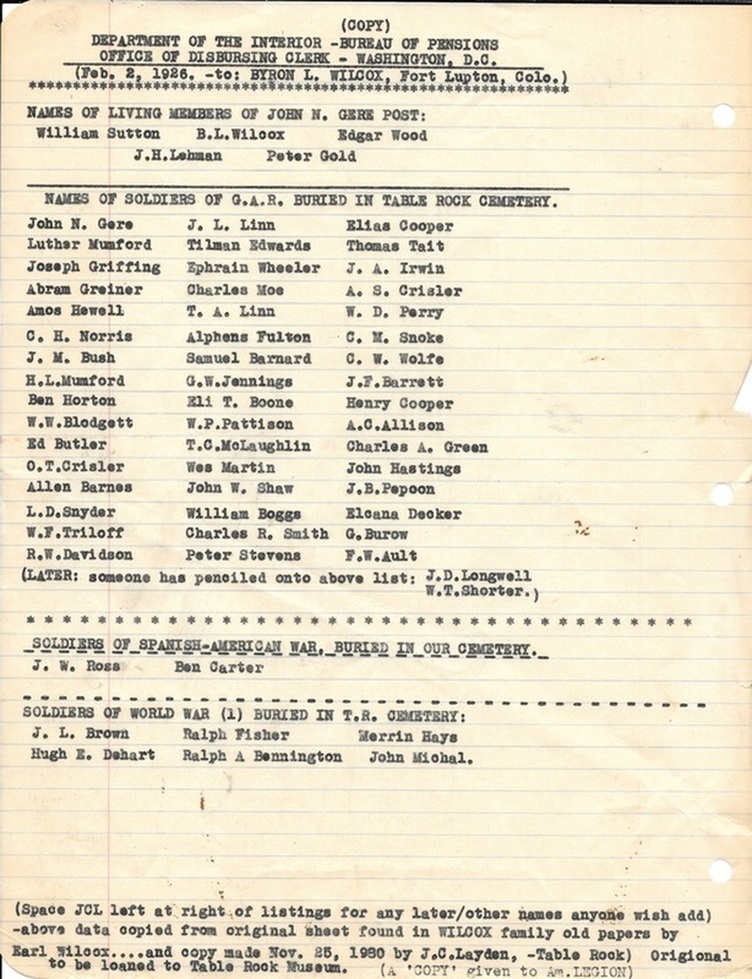

Sometime between Decoration Day 1901 and February 1926, Wilber Perry passed away. The Bureau of Pensions, Department of the Interior, prepared a list of Civil War veterans buried in the Table Rock cemetery. He was on the list.

Between 1880 and 1926 is quite a gap. We continued searching by checking the database of burials created and maintained by the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. He was not listed.

The next clue was an entry in a grave registry maintained by the Civil War Museum in Nebraska City, Nebraska. It gave a date of death, although no source was listed. March 26, 1907.

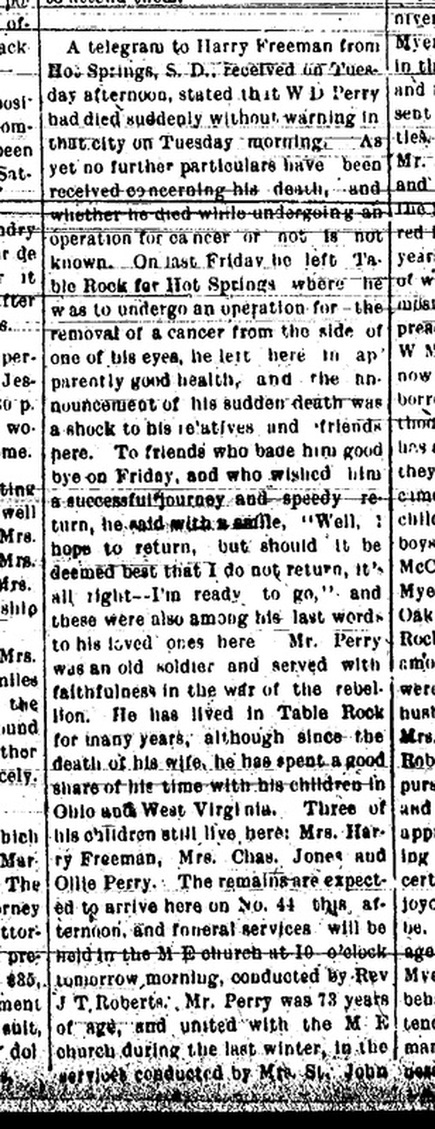

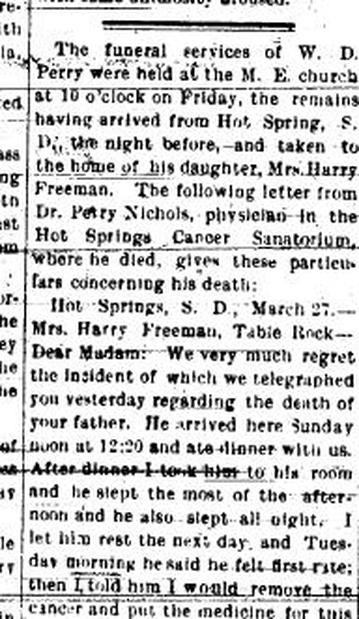

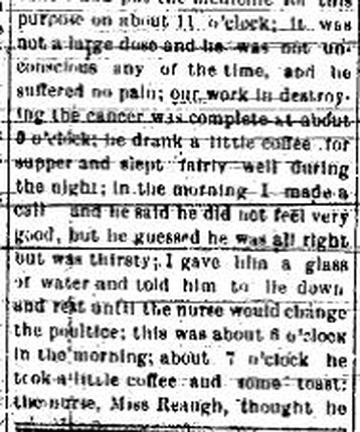

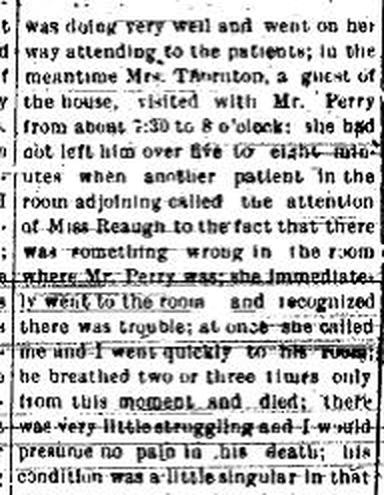

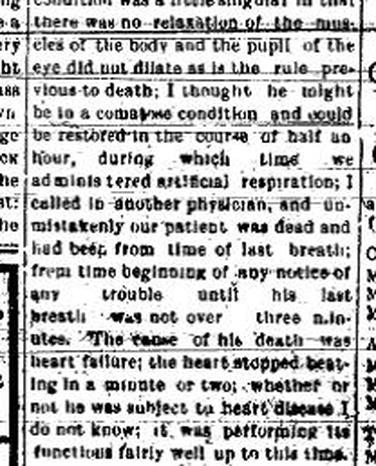

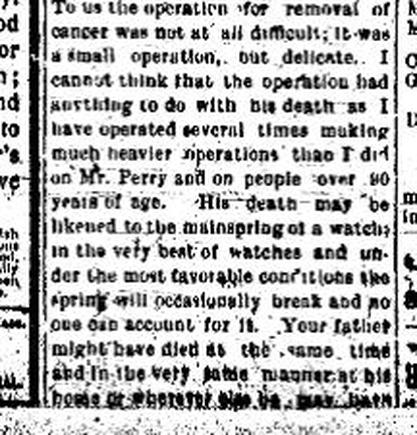

With the date of death, we went to the archives of the Table Rock Argus. Voila! Information about his death, citing death while getting medical treatment in South Dakota, telling that his body was being brought back to Table Rock on Train No. 44, and then, in the next edition, taking note of his funeral, a unique letter from the treating doctor at his bedside when he died, telling about his final hours, and finally, a "card of thanks" in the newspaper from his family thanking the town during their time of grief.

notice of his death, in the march 28, 1907 argus

an article about the funeral services, with a letter from his attending physician at the time of his death, from the april 4, 1907 argus

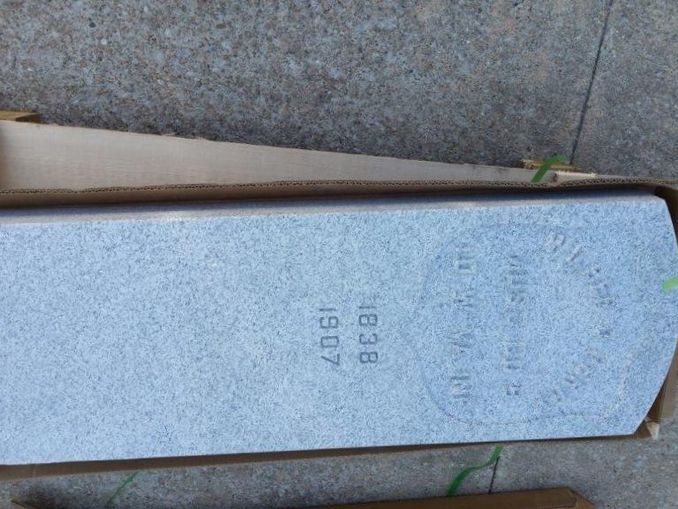

IN FEBRUARY 2016, A MILITARY TOMBSTONE was APPLIED FOR

Until the news articles about how his body was brought to Table Rock were located, it was not certain that Wilber Perry was buried here. However, we did know that he purchased three cemetery lots in the Table Rock Cemetery and they were deeded to him on May 31, 1894, according to Cemetery Board records. His wife Hester's grave, in Lot #3, is marked by a nice tombstone. Until about five years ago, a G.A.R. flag marker for Mr. Perry nestled against one side of Hester’s tombstone but it is gone now. Those flag holders are placed at the graves of Union Civil War veterans. Those who placed that marker would have known him personally, as many were still alive in those days. We can now be certain, with the cemetery data and the funeral information, that he is buried there rather than the marker merely being an honorarium, which would be extremely unusual in any event.

On February 10, 2016, the Table Rock Cemetery Association and the Table Rock Historical Society applied for a military tombstone to mark Perry's grave. The federal government provides these tombstones for free, but they must be installed with private funds. Here is the application; scroll down to see the full cover letter, the application, and the documentation submitted with it.

On February 10, 2016, the Table Rock Cemetery Association and the Table Rock Historical Society applied for a military tombstone to mark Perry's grave. The federal government provides these tombstones for free, but they must be installed with private funds. Here is the application; scroll down to see the full cover letter, the application, and the documentation submitted with it.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

The application was successful. In April 2016, Wilber Perry's military tombstone was installed.

what kind of man was he?

In the search for the evidence necessary to support an application for a military tombstone, we found three direct descendants of Wilber Perry, the wife of Dave Etherton, Mara Blake, and Tom Freeman. None had known when Wilber had died, and were grateful to have the information they had long sought.

Mara's grandmother had long sought information about Wilber's demise, Wilber being her grandfather. She is gone now, which is sad, as the rare information provided in the two Argus articles would surely have been satisfying to her.

Mara's grandmother, while she did not know how or when Wilber died, has passed on to us some snippets about Wilber. Mara has passed on her grandmother's notes about her grandmother's grandfather. These notes mention others, including the grandmother's dad, Oliver Perry. This is the full text of what Mara provided, along with her annotations about some of her grandma's writing that she could not decipher:

Mara's grandmother had long sought information about Wilber's demise, Wilber being her grandfather. She is gone now, which is sad, as the rare information provided in the two Argus articles would surely have been satisfying to her.

Mara's grandmother, while she did not know how or when Wilber died, has passed on to us some snippets about Wilber. Mara has passed on her grandmother's notes about her grandmother's grandfather. These notes mention others, including the grandmother's dad, Oliver Perry. This is the full text of what Mara provided, along with her annotations about some of her grandma's writing that she could not decipher:

Wilbur Devello Perry died in Rapid City [it was Hot Springs actually], S.D. – A cancer above an eye-qA operated on, HE died there on day he was to come home. At first IT WAS thought it was a heart attack- but later said the cancer had probably struck his brain-not all removed.

Orville said he was such a wonderful little old man.

He had taken Ollie, Uncle Allen and Aunt Hattie back to W. Va. after Grandma died, for a few years.

They came, Grandma & Grandpa, from W. Virginia, where all the children were born except dad (and maybe Uncle Allen). They lived in Pawnee County, where dad was born.

Grandpa was a laborer. He sold garden vegetables & worked in stores at different times. (Dad, as referenced here by my grandma would have been Oliver Lee Perry)

During the Civil War, he was in the Fife & Drum Corps. He was a drummer and afterward had what was called a drummer’s hand. (Dad also had talked of a hernia.)

He was in Libbey Prison in Richmond, VA. It has been moved to Chicago (bldg.) for the World’s Fair. (The Confederate Museum in Richmond, VA.-has mementos of Libbey Prison.)

'

Grandpa received a settlement from the government, then received a pension-for the rest of his life.

The hospital in South Dakota that Grandpa was in (it was not a veterans hospital) moved to Savannah, Missouri; it was called Dr. Nickle's Cancer Hospital. Aunt Hattie had cancer (?? Eyelid & nose) removed there, about 1929. Orville had a cancer in the 30’s, (??) had a breast removed in 1945 at same hospital- hospital. It closed about 1957 or 1958). (??- in the last sentence here could say “Lona” but is very difficult to read.)

Grandpa took three children back to W. Va., stayed with Grandpa’s sister for some time. Her name was Celia Gould; she had married Jay Gould’s brother (lots of money). She was good to children. “had 3 children (the “” is located directly under Celia’s name in the second sentence)

One sister of Grandma’s was very unkind to Ollie, Allen and Hattie- they didn’t talk much about it. Aunt Hattie was about 10 when Grandma Perry died.

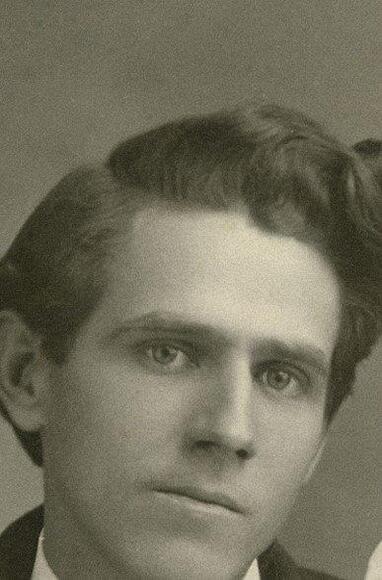

what did he look like?

When he enlisted in his early 20s, he was 5'6", had brown hair, and blue eyes. So one of his military records said:

Wilber's son Ollie reportedly described his father:

He was such a wonderful little old man. |

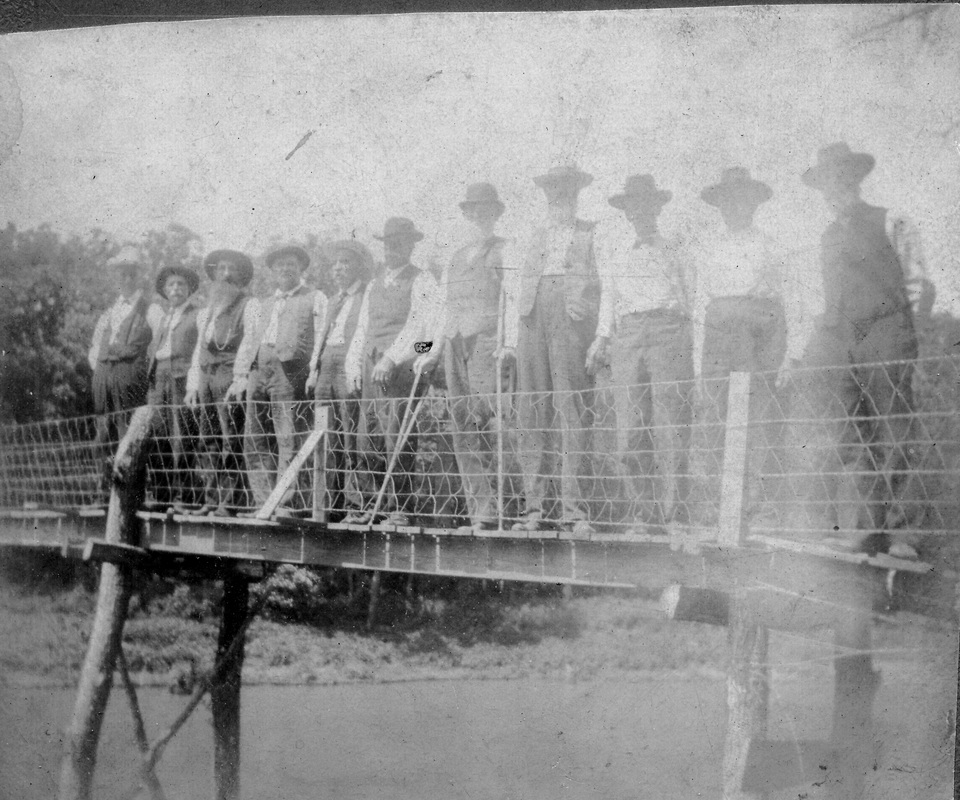

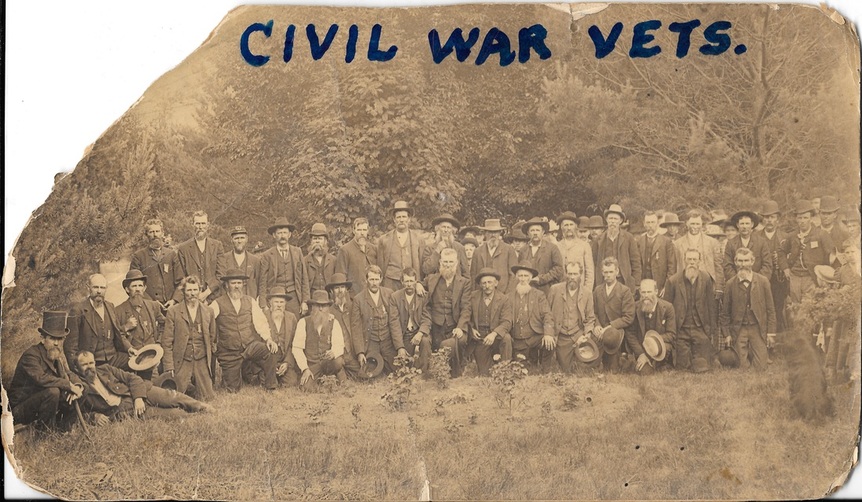

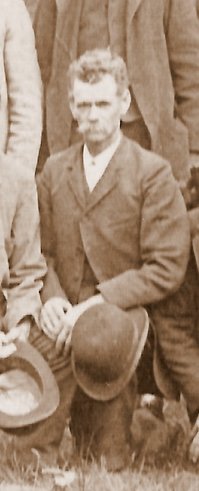

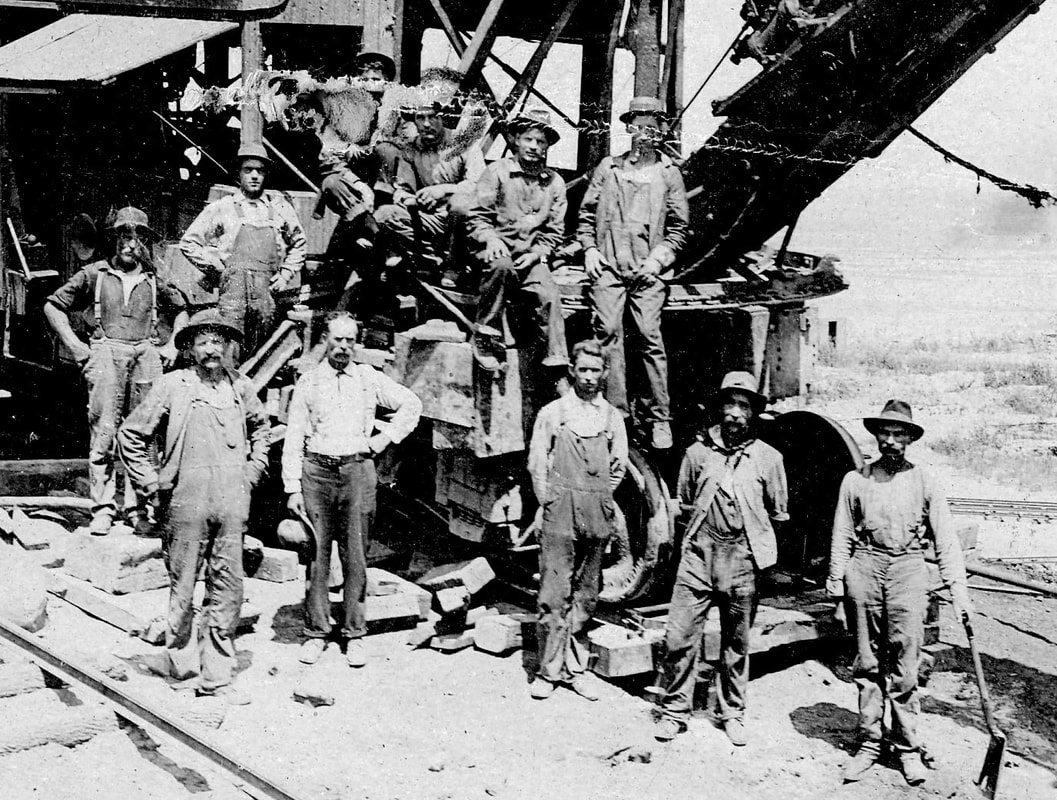

Is he in this photo?

This photo was taken in 1887. Wilber would have been only 47 at the time of this picture. He may have been a "little" man in his old age, but what did he look like at that age? He was short for our time, 5'6" but how tall were these other veterans?

At the May 2016 dedication of Perry's tombstone, descendants studied this photo. None had ever seen an image of him, but based on what their extended family members looked like, and with a variety of supporting observations, their best guess was that their great-great grandfather Wilber D. Perry is indeed in the picture, and that he is in the front row, fourth man from the right, specifically this man. This is a guess -- call it an educated guess -- that this is Wilber D. Perry:

If that is Wilber Perry, then you can probably see him in this photograph, too:

This is all we know of Wilber D. Perry. For now.

wilber d. perry

civil war veteran

a long ago citizen of table rock, nebraska

dedication of the military tombstone of wilber d. perry

In May 2016, the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War conducted a solemn dedication ceremony.

preparations - a slide show

the opening of the ceremony

the "badges of honor"

This moving portion of the day follows the burial ceremony of the Grand Army of the Republic. It begins with a declaration:

As we remember Musician Wilber D. Perry, let us cherish his example as a patriot and defender of those principles he believed to be right. Let us forget his failings, for he was human, remembering only his virtues. Let us so live that when that time shall come those we may leave behind may say above our graves, "Here lies the body of a true hearted, brave and earnest defender of the Republic!'" |

Soldiers place a musket with fixed bayonet, a canteen with a haversack, and then a knapsack leaning against the stock of the musket.

Then tributes, sometimes known as badges of honor, are placed, each with a symbolic meaning. The tributes were once laid by Brothers and Sisters -- old soldiers of the Grand Army of The Republic, or their “allied order,” the Women’s Relief Corps.

The ceremony adapted the traditional ceremony, which goes something like this:

Then tributes, sometimes known as badges of honor, are placed, each with a symbolic meaning. The tributes were once laid by Brothers and Sisters -- old soldiers of the Grand Army of The Republic, or their “allied order,” the Women’s Relief Corps.

The ceremony adapted the traditional ceremony, which goes something like this:

The tribute of a wreath of evergreen, “symbol of an undying love for the comrades of the war." |

Video slide show with music:

|

21-gun saluate and taps

closing prayer:

It seems well we should leave Comrade Wilber D. Perry to rest in honor where over him will bend the arching sky, as it did in great love when he pitched his tent, or lay down, weary and footsore, by the way or on the battlefield for an hour's sleep. As he was then so he is still - in the hands of the Heavenly |

descendants at the ceremony

Joining the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War and the Table Rock American Legion, family members of Wilber's daughters Lizzie and Hattie gathered. Lizzie's family included her great grandson Tom Freeman and the children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren of Tom's brothers Rob and Rich (mostly Pawnee County, Nebraska and Iowa), and Hattie's grandchildren, the Sejkora family of Burchard, Nebraska.

Mara Blake traveled from her home in Colorado to lay the rose at the ceremony. She shed tears after the ceremony as she thanked Bill Dean, state commander of the Sons, who had organized ceremony. "That's why we do what we do," Dean said afterward.

Mara's persistence in finding her great great great grandfather's resting place led to this ending. No one knew where Wilber D. Perry was buried until her collaboration with the Table Rock Historical Society resolved the mystery. "I wish my grandmother could have been here," she said. Her grandmother, now gone, had spent many years trying to find the information. Her grandmother's notes provided Mara with the information needed for what proved to be a successful launching point.