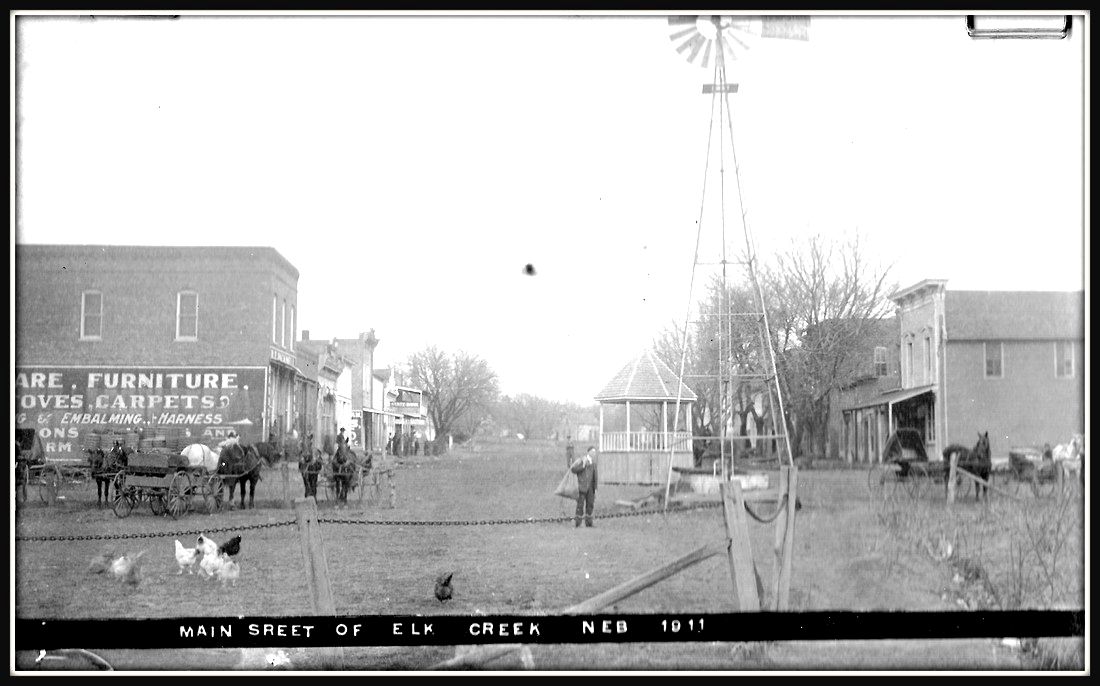

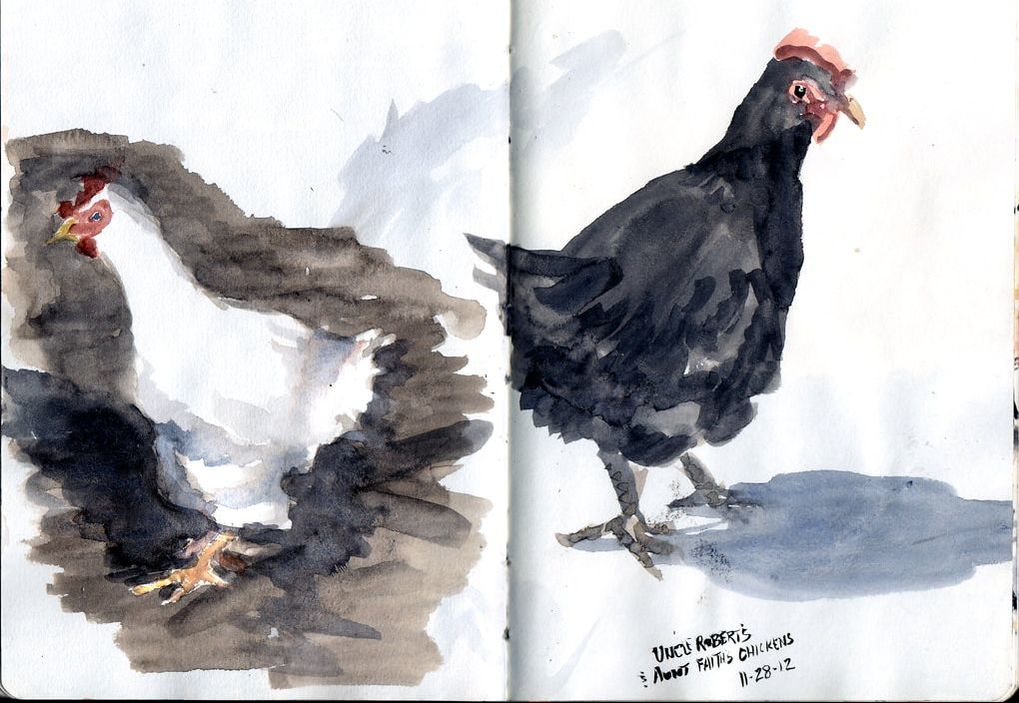

just chickens & eggs

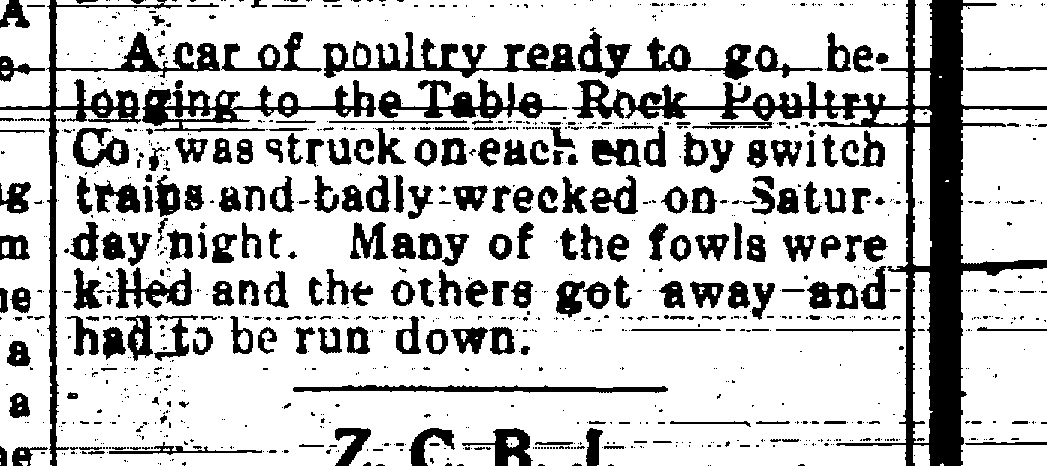

chicken thieves everywhere!

may 1920 -- buy your little chicken feed, cracked corn, and oyster shells from mr. fencl!

Oyster shells were fed to chickens as a supplement, worked a little better than gravel, etc.

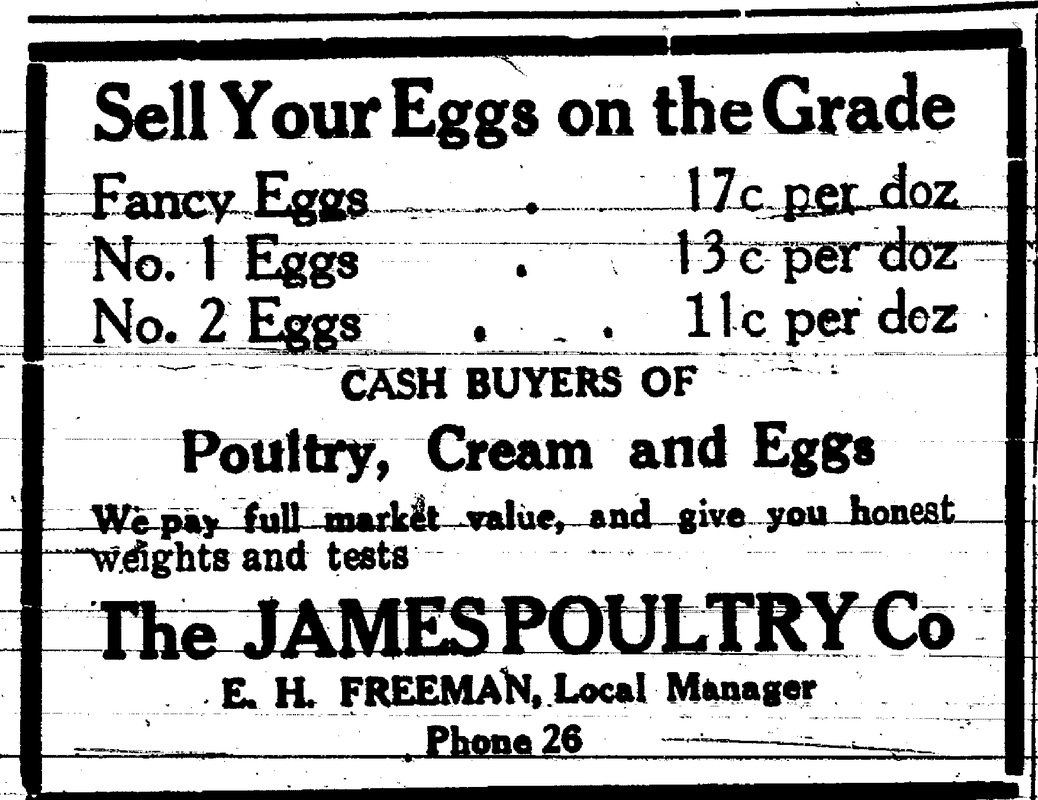

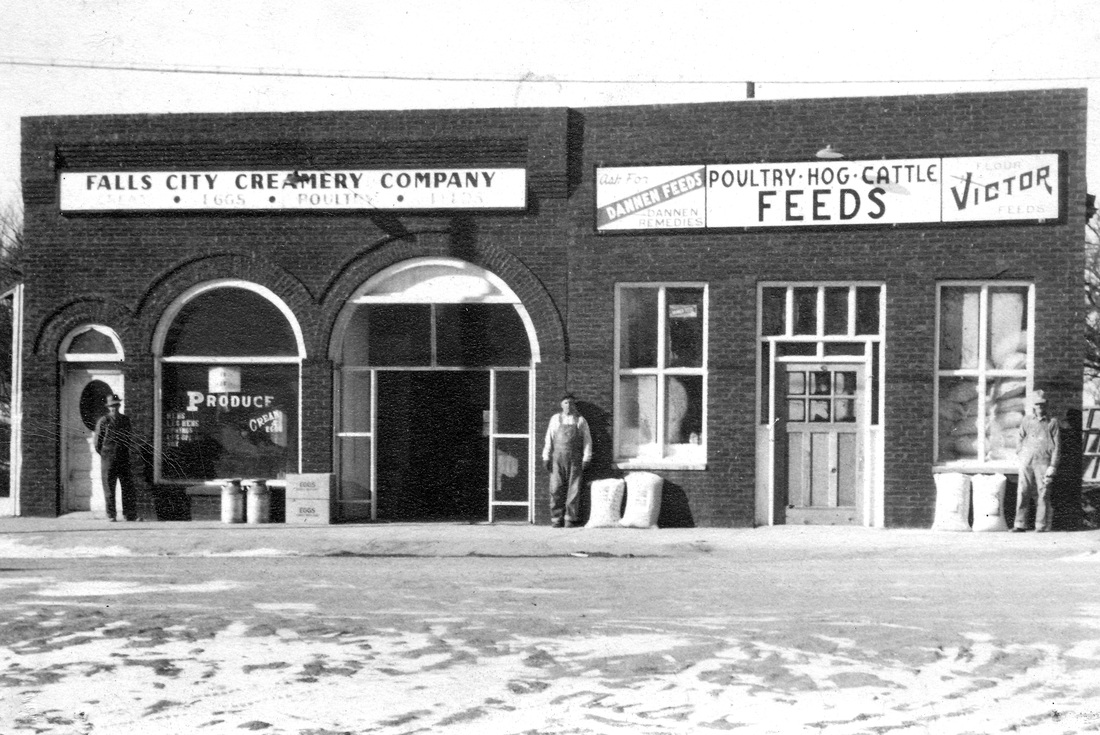

buying groceries with eggs

|

Regarding "tradin"... Whenever my grandma went to "the store" she went to "do her tradin'."

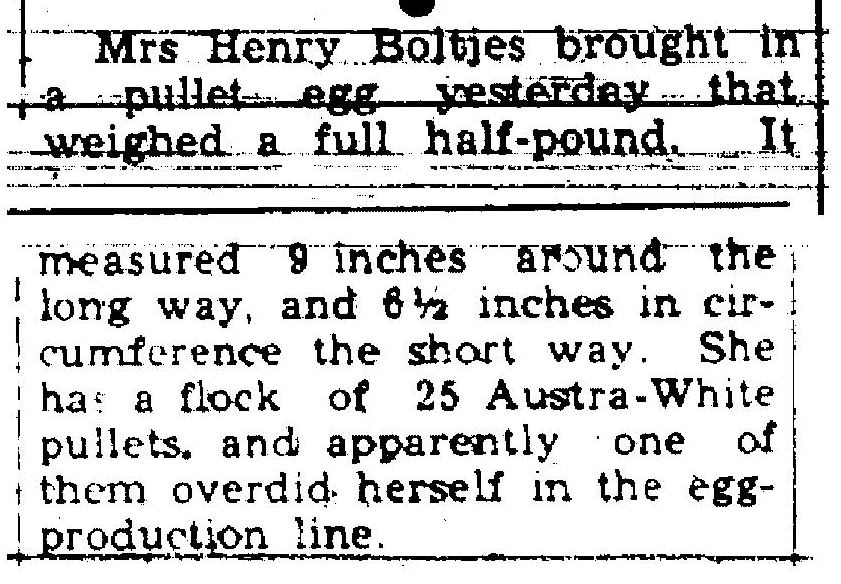

I was able as a sophmore in HS back in '52 to work in a grocery store. Lots of the "folks" did, indeed, bring in eggs "in trade" for their groceries. We had one special lady whose eggs were far far above the usual and were in high demand. We always had orders for more of "Mrs. Minter's eggs" than she brought in. Them was "the days." PETE HEDGPATH November 2019 Editor's note: Pete is not from Table Rock so you won't find anything else about Mrws. Minter's eggs, but he's a member of our Facebook group and his memories are universal for small town Nebraska! |

|

After high school graduation, I stayed at home and helped with the farm. Times were hard. One of the two Dubois grocery stores, the Farmers Union Store, bought eggs and cream. On Saturday, we took our eggs and cream to town to buy groceries with.

EVELYN MACH PETTINGER January 2019 In an interview on the occasion of her 100th birthday Editor's note: Evelyn grew up in Dubois. Again, her memories are universal for small town Nebraska! |