the feeding, watering, & fixing of

locomotives

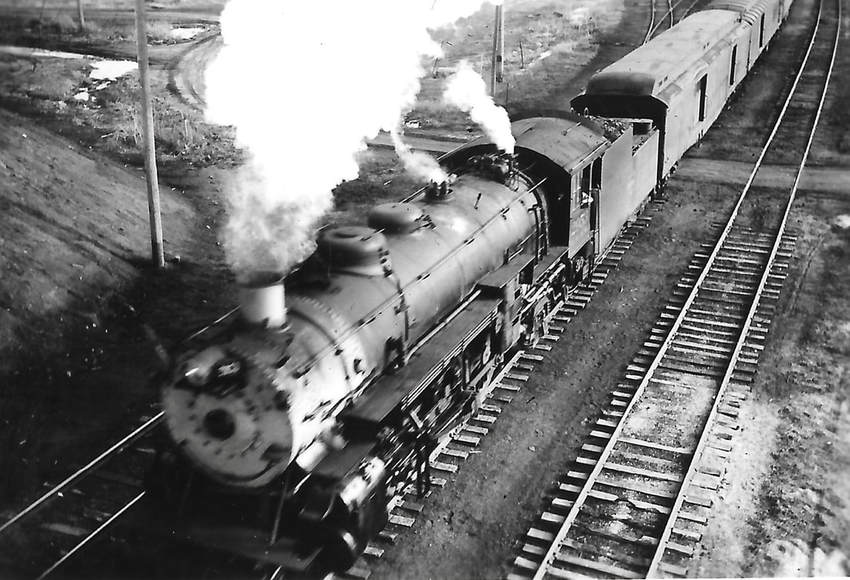

Before looking over our photoraph page, take a look at this excellent closeups of how a steam locomotive works

|

|

|

The subject of coal, water, and maintenance for locomotives is nicely addressed in a discussion at American-Rails.com:

The operations of steam locomotives are relatively simple, which I will try to explain just briefly. |

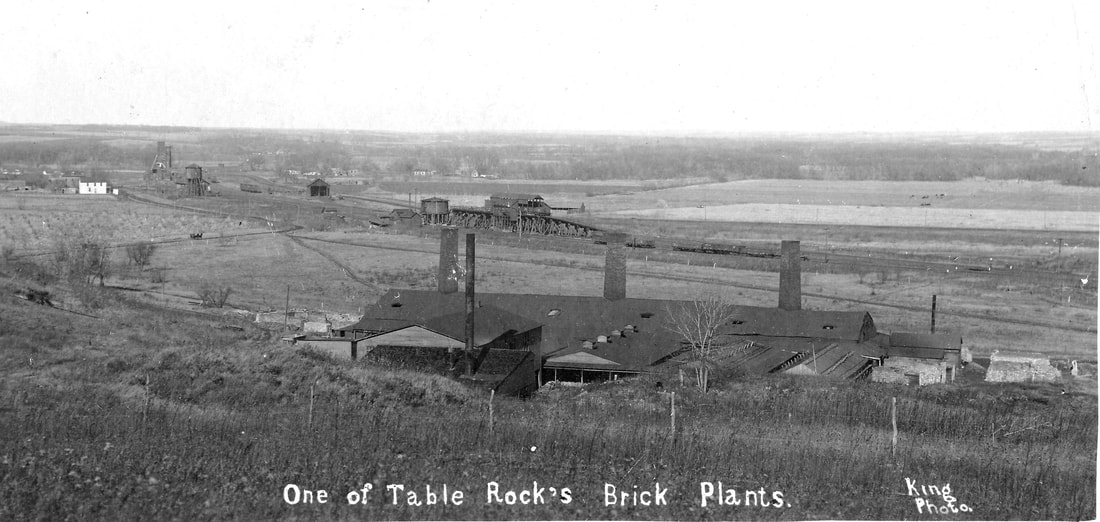

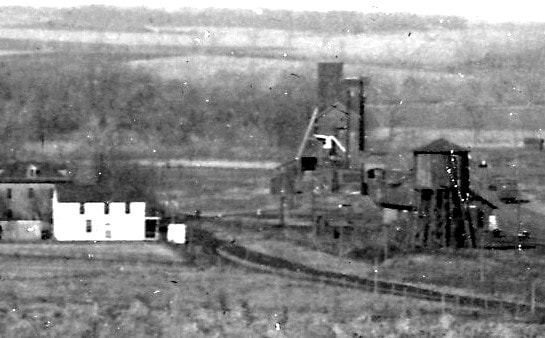

the depot area in 1908

shows structures for coal, water, & maintenance

In this photograph taken from the bluff above the south brickyard by Archer King, the depot area is laid out with considerable clarity. It tells us much about the services provided the steam trains, with facilities for water, coal, and repair, as discussed below.

coal

general information

Coal was the fuel used by the locomotives coming to Table Rock, a long succession of which began in 1871. How much coal was needed for any one locomotive depended on many variables. Here is one discussion at cstrains.com:

As a rule of thumb, it depends on the size of the thumb... |

According to a discussion www.quora.com:

The skill of the fireman is important. He needs to keep the firebox hot (obviously!). If he puts too much coal on at once, it doesn’t burn efficiently. There’s lots of black exhaust, which is effectively wasted energy. “Little and often” is the mantra, perhaps 6 to 9 shovels about every 3 minutes, but it varies according to the work being done |

larry layden remembers his years on the railroad

Larry Layden is a lifetime member of the Historical Society and a 40-year railroad man on the Burlington lines. He remembers working with older workers from the days of steam locomotives. Here's one memory of his about coal and the scooping thereof:

When I hired out in ‘61 there were still a number of ex fireman around. They had backs so wide they had to walk through doors sideways.

I talked to one who said he would have to shovel 10 tons or more of coal during a 100 mile trip. The modern coal cars used in the 1970s held 100 tons, so in five trips 100 miles up the track and back would require the fireman to shovel the equivalent of one of those modern coal cars. Of course, the steam locomotives did not pull cars of coal. They pulled tenders which carried coal and water,or sometimes wood and water.

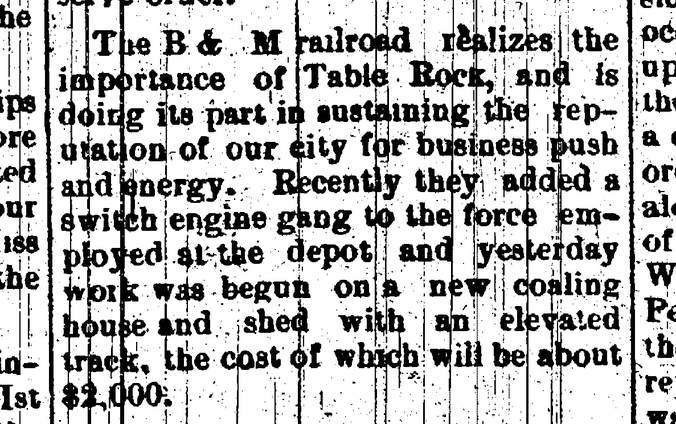

GETTING coal TO THE DEPOT FOR THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVES

In this detail of Photo 124, an area to the upper center of the photograph, there appears to be a cluster of older structures, including a water tower that is far smaller than at the more modern facility to the left, and a coaling house and shed with an elevated track. These were apparently built in 1898, as reported in the October 6, 1898 Argus:

the frame coaling tower

The tall angular building is a wooden coaling tower (apparently known also as a coal chute). It may have been the original one. Retired railroad man Larry Layden notes that it "looks like that tower is north of where the Reno is now. About where the old junk yard was."

He continues, "It could be that the new one was built to the south of that to be closer to the new water well. I know the railroad had trouble finding water. Still, it is a strange location considering how hard it would be for Wymore Line trains to coal up."

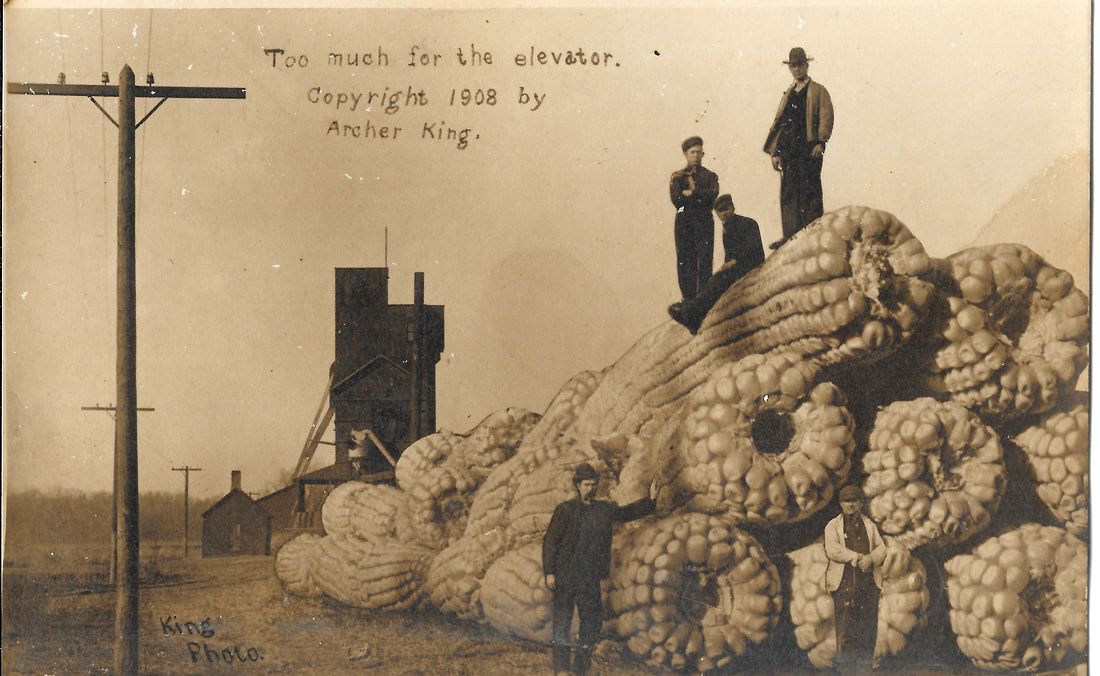

In 1911, the frame coaling tower in the distance was superseded by a steel coal chute; it may have remained standing but unused for some years. The same year that Archer King took the picture above, he also made one of the novelty postcards he was famous for. King melded different photographs to alter proportion. His photograph of the coaling tower in the background yields details not seen elsewhere.

He continues, "It could be that the new one was built to the south of that to be closer to the new water well. I know the railroad had trouble finding water. Still, it is a strange location considering how hard it would be for Wymore Line trains to coal up."

In 1911, the frame coaling tower in the distance was superseded by a steel coal chute; it may have remained standing but unused for some years. The same year that Archer King took the picture above, he also made one of the novelty postcards he was famous for. King melded different photographs to alter proportion. His photograph of the coaling tower in the background yields details not seen elsewhere.

The frame coaling tower was apparently left in place, as can be seen in this photograph taken in front of the Hotel Murphy, which was across from the depot. It was taken in the 1920s, and shared by Ted and Nancy Quackenbush.

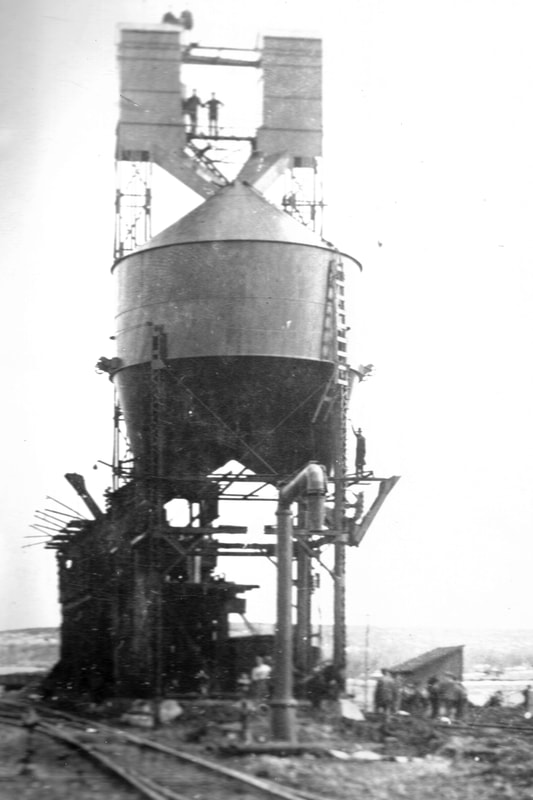

the steel coaling tower built in 1912

Historical Society member Larry Layden forwarded transcripts of articles from Mike Bartles, The Lincoln Star reported on August 5, 1911 that the Burlington was making extensive improvements in its yards at Table Rock, including "new automatic coal chutes." The Nebraska State Journal reported on April 6, 1912 that the Burlington was "installing a new steel coal chute at Table Rock, one of the first of this pattern to be built in Nebraska."

MORE COAL CHUTE NEWS

The September 27, 1912 Lincoln Star reported a tragic accident. "Theodore Broders young married man, was caught by the cable of the coal chute here yesterday afternoon and dragged to his death in the machinery." John Theophil Broder, known as "Tiffle," was only 21. He and his wife Rose had been married only about a year and a half. Tiffle was one of six children of Frederick Broeder, who had immigrated to Table Rock from Germany in 1890. Tiffle and his brother Herman were young children when their father married a girl from Steinauer, Mary Fournell, in 1891. Both Herman and Tiffle were railroad men; Herman, too, was killed on the job at the Wymore train yards in 1936 when Burlington Freight Train No. 93 struck a gasoline transport truck.

The July 30, 1956, Star said Farmers Fertilizer Service has purchased a coal chute and tower on Burlington property at Table Rock and will convert it into a fertilizer mixing plant.

The September 27, 1912 Lincoln Star reported a tragic accident. "Theodore Broders young married man, was caught by the cable of the coal chute here yesterday afternoon and dragged to his death in the machinery." John Theophil Broder, known as "Tiffle," was only 21. He and his wife Rose had been married only about a year and a half. Tiffle was one of six children of Frederick Broeder, who had immigrated to Table Rock from Germany in 1890. Tiffle and his brother Herman were young children when their father married a girl from Steinauer, Mary Fournell, in 1891. Both Herman and Tiffle were railroad men; Herman, too, was killed on the job at the Wymore train yards in 1936 when Burlington Freight Train No. 93 struck a gasoline transport truck.

The July 30, 1956, Star said Farmers Fertilizer Service has purchased a coal chute and tower on Burlington property at Table Rock and will convert it into a fertilizer mixing plant.

Beginning at 2:48 of the following video is an exhibition of how a steam locomotive was coaled and also how the ashes were removed:

water

Locomotives needed water.

According to American-Train.com, for locomotives in the 1900s,one expert said

According to American-Train.com, for locomotives in the 1900s,one expert said

A general rule of thumb pertaining to a steam locomotive's water consumption is as follows (again, these numbers are general as obtaining correct figures is specific for each individual steam locomotive requiring precise equations relating to BTU's per minute divided by the fuel being used [among other calculations, as the locomotive's drawbar horsepower is also needed to achieve correct figures].

During light working conditions, 18,000 pounds of water are needed to be available per every ton of coal consumed.

In moderate working conditions, 13,000 pounds of water are needed to be available for every ton of coal burned.

Finally, with heavy working conditions, 11,000 pounds of water are available for every ton of coal consumed.

These numbers were derived using post-20th century, modern locomotive designs. What began as such a simple device became a highly advanced machine by the 1940s. The tender could greatly extend a locomotive's range /

Of course, liquid H2O was always the most precious commodity; railroads typically placed at least one water tank, plug (similar to a tank but without a storage device and only tall enough to fit over the tender with a discharge chute which pumped water), or "tank pond" (located near the tracks they were fabricated by damming nearby creeks or streams) half-way between terminals as a safety precaution.

In Table Rock, the water for the steam locomotives came from the nearby Nemaha River, at least in times remembered. There was a pump station at the river, now long gone. Lifetime Historical Society member Robert Warren remembers it. His parents Frank and Nettie Warren and he and four brothers lived by it. His father tended it. He helped. During a 2017 visit to the museums, Robert shared many members, including these about the pump station:

My dad worked for the railroad. We came to Table Rock in 1932 and left in 1950, going back to Wymore, following his job with the railroad. We lived at the railroad pump station on the west bank of the Nemaha. Water was pumped up for the railroad.

For the first years, we lived in two railroad cars set at an angle. One had the bedrooms.

There were three pumps.

There was a big diesel engine that ran them, with a big fly wheel. The engine would “hit and miss” all the time.

Dad had to watch over the pumps. I helped. All five boys helped. We put in chemicals – lime, soda ash, and ____________ to soften it for train tanks.

We boys had to do yard maintenance and if there was trouble at the river we had to scoop sand.

I think you still see the footing where the pump house stood. I haven’t been down there for a long time, and now the road going out there is gone.

My older brother Orville survived scarlet fever, thanks to Dr. McCrea. However, Orville was killed out on a curve south of town a week before graduation.

By 1941, we were out of the boxcars. The railroad had built us a house. It may not have been much to someone else. It was made out of plywood inside and out and had a tar paper roof.

The following video begins with a showing of how water is added to a steam locomotive:

maintenance

According to American-Train.com:

By the late steam era (1930s-1940s) a locomotive used in main line service could run anywhere between 75 to 150 miles before needing to refuel, which typically coincided with a train crew's district/territory.

This distance was also how far most railroads placed maintenance terminals/facilities since steamers needed constant care whether it be lubrication, fuel, sand, or some other requirement.

The Lincoln Star article of August 5, 1911 that reported on the Burlington's extensive improvements of the yards noted that a roundhouse would be erected "to replace the one that was burned a year ago." Is that the "old" roundhouse slightly to the left in this detail of the 1908 photo above? There don't seem to be tracks going up to it.....

The roundhouse's primary function was for storage and maintenance of steam locomotives. |

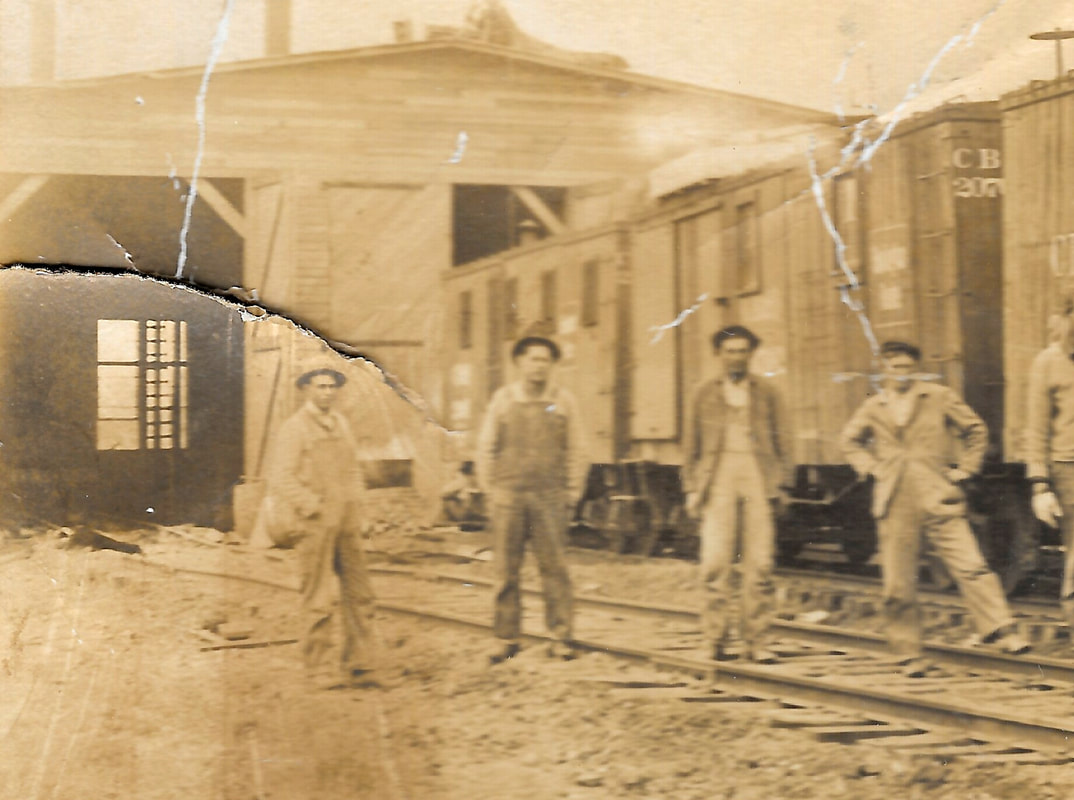

Below is a view of the back of the roundhouse that was used in 1908 (or one of them if there were an "old" and a "new" before one was built in 1912.

These cheerful fellows are standing on an engine that went out the back wall of the roundhouse. John A. Barnes is probably not one of them....

These cheerful fellows are standing on an engine that went out the back wall of the roundhouse. John A. Barnes is probably not one of them....

Table Rock Argus, Oct. 8, 1908.

Last Tuesday morning while at work around the engines in the round house, Foreman J. A. Barnes met with quite an accident.

He had built a fire in No. 119's engine and had gone over to the next stall to do some work on the switch engine; he had not worked very long when he noticed the other engine was in motion.

He tried to stop the runaway but before he could gain the cab entrance the monster had started through the back end of the round house, and before John could get out of the way, he was caught by some of the falling timbers and pinned to the ground, fortunately all the large pieces missed him and he only sustained a few bruises which layed him up for a few days.

All of the engine left the track through the rear end completely caving it in and miring in the mud so that it took three engines to pull it back on the track.

the roundhouse built in 1912?

How old is this undated photo? The man at the far left is identified as Vess Harris. He was born in 1882 and was thus about 30 when the new roundhouse was built in 1912. How old does he look in this picture?

no turntable at the roundhouse but table rock had a wye

Retired railroad man Larry Layden recalls about Table Rock and its trains:

Steam engines had no directional preference. Push, Pull, forward, backward, all the same to a steam engine. An advantage of the diesel electric was they had controls on both ends, front and back, so they could easily run in any direction.

The direction of travel of both a steam and diesel engine was controlled by what was called a reversal lever. Push it forward and go forward, backward to back up. Pull it out and take it with you and it would not move. The engineers were supposed to do this when they left the engine unattended.

Information about turntables gleaned from the book "The Wymore Story" by Dick Bartels. Regarding turntables. They were usually found at division points, like Wymore, Lincoln, and St. Joe. Table Rock did not have a turntable.

The “wye” was used to turn engines and entire trains. [Table Rock has a “wye,” which is a section of track off the main line where the train could back up on one angle and then pull forward on another.] Think they [the locomotives] were 100 feet long, to hold engine and tender. Today's diesel engines are around 75 ft long.

[Where there were turntables] [s]ome were turned by electric motors but many were turned by men in the pit under the turntable track. Think there was a turntable at Falls City but it might have been on the Missouri Pacific.

Wikipedia has a more detailed explanation of the use of a wye:

In railroad structures, and rail terminology, a wye...is a triangular joining arrangement of three rail lines with a railroad switch (set of points) at each corner connecting to each incoming line. A turning wye is a specific case.

Where two rail lines join, or in a joint between a railroad's mainline and a spur, wyes can be used as a mainline rail junction to allow incoming consists ability to travel either direction, or in order to allow trains to pass from one line to the other line.

Wyes generally cover less area than a balloon loop doing the same job but at the cost of two additional sets of points to construct, then maintain.

These turnings are accomplished by performing the railway equivalent of a three-point turn through successive junctions of the wye. The direction of travel and the relative orientation of a locomotive or railway vehicle can be reversed, resulting in it facing in the direction from which it came.

tIn the picture below, taken by Arvid Blecha in 1941, the wye is in the foreground, with a house set on the north (far) side of one point of the wye. The mainline runs off to the right of the picture. The switch to the "stem" of the wye is out of sight, to the left of the picture. This wye was presumably still in use, as steam locomotives were still very much a part of rail transportation in 1941. In fact, Arvid took the picture of the locomotive at the top of this webpage in 1941 as well.