remember pearl harbor.

On December 7, 1941 at 9:48 a.m., the attack on Pearl Harbor began. 18 ships were destroyed. More importantly, 2,043 men lost their lives.

In the table rock argus

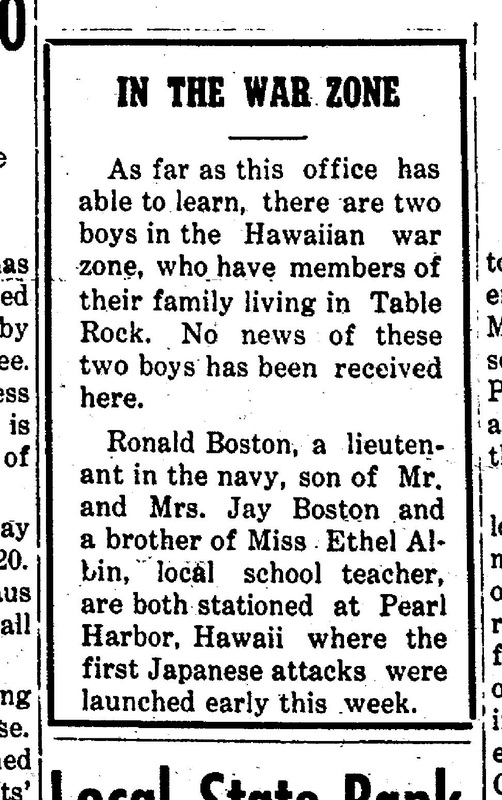

I expected to see the typical BLARING HEADLINE that war had been declared. But there wasn't. There was just a little insert on the front page mentioning that there were two local boys who were believed to have been in the Hawaii war zone and there whereabouts were unknown. In those days, there was a pre-printed insert that carried all the national and international news, and it appears that Rudy left it to the insert on December 11, the first edition after the Pearl Harbor attack. Of course, I don't suppose he had access to the AP! It was just the insert.

In October, 1941, defense was an issue -- there was a County Defense Fair. A Navy recruiting ad. And listen to the Huskers on the radio!

In the edition two weeks before the attack, November 27, 1941:

The last edition before the attack, December 4, 1941, the local news was pretty normal, although the insert had a bit more.

December 11, 1941 -- the first edition after Pearl Harbor. The local news on the front page refers to Hawaii, but there is no announcement of the attack or discussion of it. Everyone knew about it, so the question was just about where the local boys were. Remember, this went to press -- in print set letter by letter -- on the third day after the attack, if it was to be mailed and received on the 11th.

The pre-printed insert that went into the December 11, 1941 Argus had obviously been printed prior to Pearl Harbor:

Other news on December 11, 1941, in both local news and the pre-printed insert. Delmar Covault gets married, & Howard Binder gets a promotion at aircraft school:

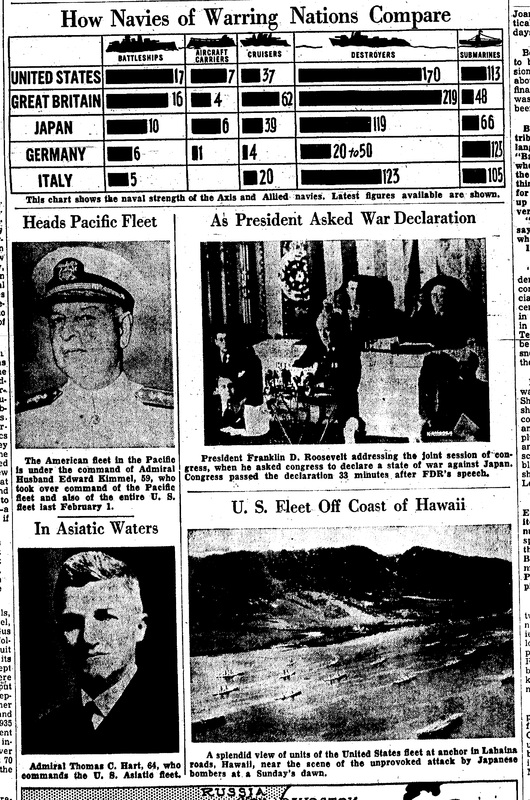

It was not until the December 18, 1941 edition that the pre-printed insert caught up with the declaration of war:

Other news on December 18, 1941:

more on pearl harbor:

The Arizona had it the worst.

1,177 of them were on the Arizona.

The sailors lost on the Arizona included my Dad Bob Sitzman’s cousin Art Dupree, who grew up in St. Joe, Missouri. Art's grandma and Dad's great grandma were sisters who, as teenaged girls, came from extreme eastern France and homesteaded in the 1860s on adjoining farms in the French Bottoms of St. Joe. Their families stayed on their farms and that's where Dad was born. Art was the oldest of a family that would grow, after his death, to ten kids, and his two youngest brothers, now elderly, still farm the land that his pioneer grandma homesteaded.

When I visited the memorial in 1982 and when I have visited with my Uncle Raymond (who was on the Maryland) and his Pearl Harbor survivor friends, they talked of how they tried to get men out of the Arizona, but it quickly became too dangerous and they were ordered to quit. They said that men were heard pounding for rescue for days. The National Park Service, which maintains the memorial, now says that all 1,177 men were killed instantly, and their bodies cremated by the initial hits and the fires that burned for 2-1/2 days.

1,177 of them were on the Arizona.

The sailors lost on the Arizona included my Dad Bob Sitzman’s cousin Art Dupree, who grew up in St. Joe, Missouri. Art's grandma and Dad's great grandma were sisters who, as teenaged girls, came from extreme eastern France and homesteaded in the 1860s on adjoining farms in the French Bottoms of St. Joe. Their families stayed on their farms and that's where Dad was born. Art was the oldest of a family that would grow, after his death, to ten kids, and his two youngest brothers, now elderly, still farm the land that his pioneer grandma homesteaded.

When I visited the memorial in 1982 and when I have visited with my Uncle Raymond (who was on the Maryland) and his Pearl Harbor survivor friends, they talked of how they tried to get men out of the Arizona, but it quickly became too dangerous and they were ordered to quit. They said that men were heard pounding for rescue for days. The National Park Service, which maintains the memorial, now says that all 1,177 men were killed instantly, and their bodies cremated by the initial hits and the fires that burned for 2-1/2 days.

319 who were on the Arizona survived; 40 of them had been away from the ship at the time of the bombing.

Family members often served on the same ship in those days, but that was discouraged after that. Of those assigned to the Arizona, there were 37 sets of two or three brothers and all of the brothers in 23 sets were killed. Only one set of brothers survived entirely, one was in San Diego and the other badly injured. The only father-son pair died.

One sailor who died aboard the Arizona was Bill Ball of Waterloo, Iowa. His friends, the five Sullivan brothers there, enlisted after hearing of his death. They enlisted together with the condition that they be assigned to the same ship and they were. They died when their ship was sunk during the battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

Family members often served on the same ship in those days, but that was discouraged after that. Of those assigned to the Arizona, there were 37 sets of two or three brothers and all of the brothers in 23 sets were killed. Only one set of brothers survived entirely, one was in San Diego and the other badly injured. The only father-son pair died.

One sailor who died aboard the Arizona was Bill Ball of Waterloo, Iowa. His friends, the five Sullivan brothers there, enlisted after hearing of his death. They enlisted together with the condition that they be assigned to the same ship and they were. They died when their ship was sunk during the battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

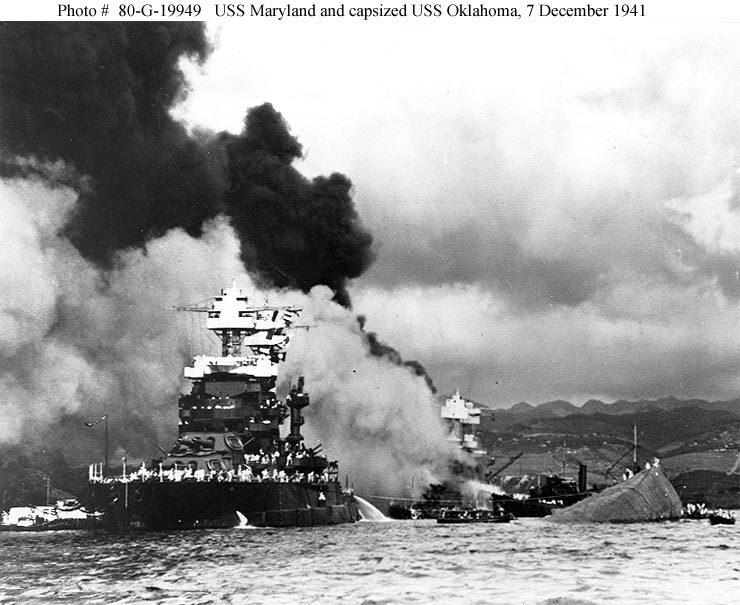

The Maryland

|

My mom Becky Sitzman’s uncle Raymond McBeth was on the Maryland, which was also anchored in Pearl Harbor that morning. Raymond was the brother of Ines Roberts, my mom's mom, who lived in Table Rock for many years. She lived across from the northwest corner of the cemetery, where Amy Hunzeker's house is now.

Uncle Raymond survived. Raymond McBeth's Story, a view from the Maryland

Raymond used to wrestle at carnivals to earn money, and his wrestling name was Sailor Mac. He spent a lot of time helping out on my Grandma and Grandpa's ferry, the Spirit of Brownville, which plied the Missouri River where the Brownville bridge now stands. Sailor Mac actually did become a sailor on the seas and not just the Missouri River. In 1941, he was aboard the U.S.S. Maryland and life was fun. I think he worked in the galley at the time but he was an electrician later on. On December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he was there aboard the Maryland. Before the attack, Pearl Harbor was nothing unusual. “It was one of the Navy's bases. I never heard of it before, but it was there. Navy yard. I went aboard in July, and we were in there a couple of times between that and when it happened.” He had been in the Navy for less than a year when the Maryland was in Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It had taken him a while to get in the Navy. He was bound and determined to be a Navy man but kept getting rejected because he had flat feet. He took to working the arches of his feet, rolling on pop bottles and felt that there was an improvement. He tried again. He went to the medical examination and was passed along but then was kicked out of line again. He was in near tears and went to the side. An officer came over to him and there was a discussion; I don’t remember the details, but someone Raymond’s persistence and determination moved that officer and somehow Raymond was allowed into the Navy. Within the year, he was at Pearl Habor. Before the attack, Raymond did go ashore. I asked if he got shore leave: “Liberty. Shore leave is more than 72 hours. They really made Honolulu a short liberty, had to be back to the ship by Midnight, couldn't stay out on the beach. Why not? It just wasn't done.” “The Oklahoma was tied to the Maryland. It was torpedoed and rolled over. She took our punishment. As it rolled, guys were climbing on ropes trying to get to the Maryland and the lines were snapping as they were climbing. And that would drop them down between them, and of course, they would be crushed between the two ships. Lines that big around, doubled over 7 and 8 times, naturally, they're not all the same tightness. You wrap those up and you wrap around and as the ship pulls away, it tightens them up. But naturally, they're not all the same. They're the same tensile, but not all that tight. So some of them give more than the others. So the tightest ones were snapping. (The guys were trying to come across on those?) Oh yeah, anything to get across.” They were able to rescue some of the men, but others fell to their deaths, were crushed between the ships. The men had to get up those ropes. The Oklahoma was rolling away from the Maryland and if jumped in that way, it would suck you under. The whirlpool of suction would suck you under.” “By that time, the whole harbor was in flame from the burning oil. (So you don't want to be in the water in any event.) You had to swim under water. Then as you break water, you take a break, you had to throw the ] burning water back and then take a breath and go under again. That was the blackest, thickest smoke I've ever seen. I was nailed for firefighting, with a fire hose, to try to keep the flames away from the ship. I was on scullery detail at the time of the attack. Battle stations were called. My battle station was manning a surface range finder for a six-inch gun. [An office came to him.] He said, Mack, I know where you are, and those rangefinders can't be used anyway, you just stay here. If I need you, I know where to come and get you. I just stayed in the scullery and watched the whole thing until an officer came by and told me to man a fire hose to keep burning oil away from the ship. So the rest of the time, I was pushing burning oil away from the ship. Like I say, that was the blackest, filthy smoke I've ever seen.” After the attack, the Maryland sent rescue parties to the Oklahoma every day. They tapped on the bottom of the ship – all that was exposed, because it had rolled over – and if they heard something, if they could, they would cut a hole with an acetylene torch and get the men out. They actually rescued a lot of men that way. The last two that they got out were a week after the attack; one was dead and the other could not see, whether due to injuries or being in the dark for a week. “When I got into Pearl Harbor Survivors, I found there was another Raymond McBeth. He come from Nebraska. I don't think we're related. But it was funny. He was on a tanker it was, I believe, and severely burned. That's how I found out about him, because I got some of the mail. Naturally, I opened the mail that had been forwarded to me without even thinking -- McBeth. Then, wait a minute. He's not me. But there it was, Raymond McBeth. I never heard from him or contacted him, just got mail addressed to him. Maybe he didn't make it? It's entirely possible, since he was severely burned. You just don't know.” In a newspaper article about Uncle Raymond's story, he said he was in the Navy for six years and during that time had just one leave, which was four years after he enlisted. He married Aunt Arline during that time. |

|