influenza in pawnee county

By Sharla Sitzman

Preface: To prepare for a newspaper article in the Pawnee Republican, I researched the county newspapers for the effects of the flu county wide. Lawrence Obrist then provided additional personal information, including about his great aunt Bertha Burgert and provided a transcript of his father's memories about the flu, which is at the bottom of this page. The articles that follows below is the final result. Some is duplicative of the Table Rock page. Where this is conflict, if any, the information on this page prevails. Sharla

The influenza pandemic happened a century ago. 1918. Pawnee County knew it was coming. The first wave of the virus had gone around the world earlier that year.

It was often called the Spanish flu because Spain was the first country without war-time censorship so the first reports came from there. But ground zero was a place well-known to many of us in Pawnee County, Ft. Riley. Most scientists now believe that the actual “spark” site was in rural Haskell County in southwest Kansas county, where a virus jumped from swine to humans and targeted many young people. It seemed to die out. However, the virus followed recruits from there to Camp Funston, a training camp at Ft. Riley, where it mutated and became a killer. As historian John Barry said in his definitive work, “The Great Influenza,” the virus “was adapting, violently, to man.” This mutated virus ran from camp to camp.

“Patient One,” i.e., the first positively identified victim of the virus, was a cook at Ft. Riley who at first seemed to have a cold; within hours others had sickened, and within little more than a month almost 1,200 soldiers were sick and almost 50 of them had died. In this first wave was Walter Blair of Dubois, age 26. The virus followed the troops to France, where it spread from Europe to Russia, India, China, and Africa.

It was often called the Spanish flu because Spain was the first country without war-time censorship so the first reports came from there. But ground zero was a place well-known to many of us in Pawnee County, Ft. Riley. Most scientists now believe that the actual “spark” site was in rural Haskell County in southwest Kansas county, where a virus jumped from swine to humans and targeted many young people. It seemed to die out. However, the virus followed recruits from there to Camp Funston, a training camp at Ft. Riley, where it mutated and became a killer. As historian John Barry said in his definitive work, “The Great Influenza,” the virus “was adapting, violently, to man.” This mutated virus ran from camp to camp.

“Patient One,” i.e., the first positively identified victim of the virus, was a cook at Ft. Riley who at first seemed to have a cold; within hours others had sickened, and within little more than a month almost 1,200 soldiers were sick and almost 50 of them had died. In this first wave was Walter Blair of Dubois, age 26. The virus followed the troops to France, where it spread from Europe to Russia, India, China, and Africa.

|

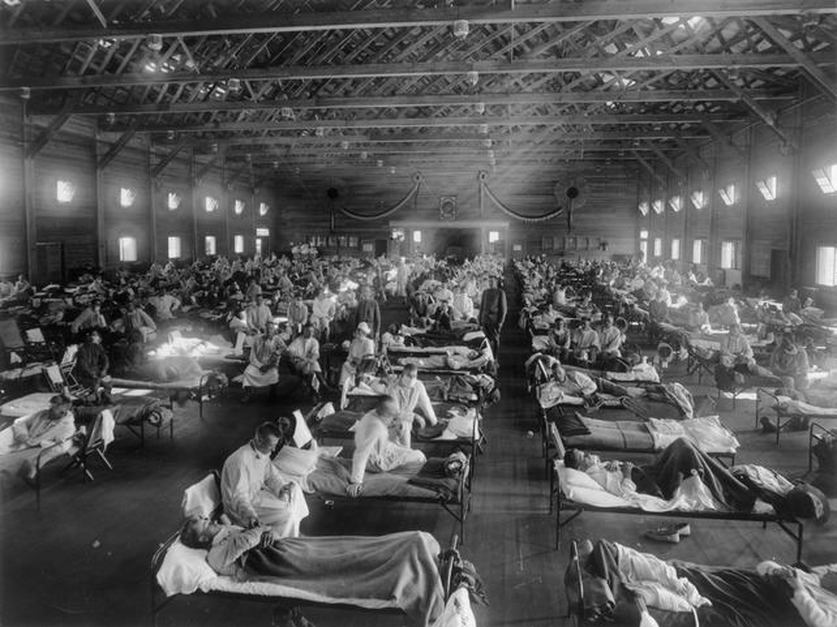

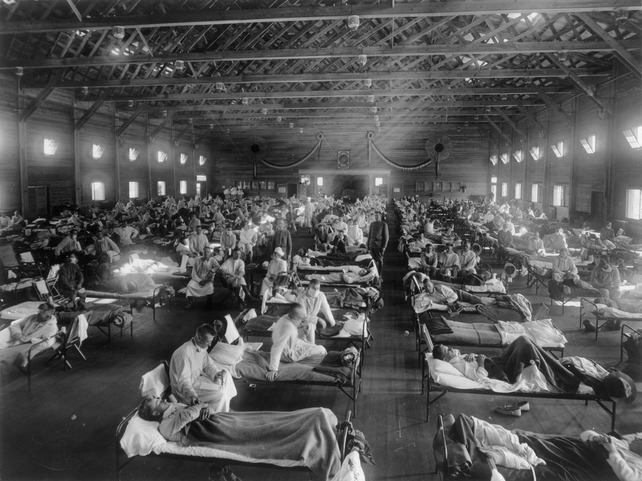

This is a photo of the Camp Funston influenza ward posted on the Historical Society's Facebook page by Lawrence Obrist. Lawrence says, "Imagine in 1918 about 5-10 men in this photo dying of the flu each day and then replaced by others."

Ray Musil says of this picture of Camp Funston, "My grandpa Mike Ullman of the Steinauer area was there at that time. He was too sick to be sent overseas so he may be one of those in that picture." |

As a precaution, in October the state health department (headed by Dr. Wilson, formerly of Table Rock) suspended indoor gatherings at places like “theaters, picture shows, and church.” However, people went about their other business. However, influenza seemed far away from Pawnee County. It came closer to home, though, as news came about the deaths of friends and relatives in cities around the country and bodies shipped to Pawnee County, the home of the heart.

The virus had died out after the summer but then mutated to an even more lethal form. The first to die of this second, deadliest, wave of influenza were soldiers in the military training camps. 22-year-old Harold Dusenbery of Pawnee City wrote home from Camp Grant (a training camp near Rockford, Illinois) to say he had suffered a “slight attack” of influenza but was on the mend. He died days later. Three others died within a month. Steinauer’s Charles Wenzl died at Camp Funston (the training camp at Ft. Riley where the mutated virus had first erupted), and two Dubois soldiers, 26-year-old Ross Irwin and 31-year-old Frank Tlustos, died at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

Flu was nothing new in those days. Usually only the very young or the very old were endangered. There had been epidemics, of limited area. However, this new flu was deadlier and seemed to target the young and healthy, especially 20 to 35-year olds.

In October, a Table Rock boy who was at medical school in Philadelphia, Lloyd Andrew (Class of 1914), wrote that the medical students had been taken out of school and sent out to care for flu victims. Drivers took them around. He had visited 35 patients a day for the past week. He wrote that when people found he was a doctor, “six or seven come and get you by the arm and drag you to take care of the sick. Sometimes I have found as many as six people sick on one house, all in one room, and no one to wait on them. Some places you find two or three dead and three or more sick in the same room, no one to care for the dead.” As many as 600 had died in one day in that city.

Locally, people went about their business during this time. As a second “incredibly deadly” wave of influenza swept through the United States beginning in early Fall, Miss Ethelwyn Bacus of Steinauer visited in Pawnee City. Mrs. and Mrs. Evert Cordell of Table Rock visited in Humboldt. Roy Leech of Oklahoma, formerly of Table Rock, visited in Humboldt. Stores advertised specials, auctions were set.

Then the area felt the full force of influenza.

In October, Roy Leech, the former Table Rocker visiting in Humboldt, died. And two women in Lewiston were sick.

Bertha Burgert of Cold Point, near Steinauer, headed for Mankato, Kansas to care for sick relatives, the papers reported. She was identified only as Mrs. Jesse Burgert, as was not uncommon. Until Lawrence Obrist recently provided information, that was about all we knew about her. She was his great aunt, his grandpa John Obrist's only blood sister. Larry says that the sick relatives were Bertha's daughters Emma and Lucy. The girls had come down with influenza while visiting relatives near near Mankato. Bertha decided to take the train to be with them. Larry says, "Her only son, 12-year-old Julius, recalled years later his tears and fears as he gave one last goodbye wave to his mother." When word came that Bertha had come down with influenza herself, Larry says that his grandpa wanted to go to Kansas to rescue her. His wife's brothers and Sam Hunzeker, her half brother told him not to go, that his own family needed him and he should risk his life. He reluctantly stayed home.

In October, Lewiston lost Miss Ada Dobson.

Then came news that Bertha Burgert had died on October 23. She was 45. Lawrence Obrist says that the daughters she had gone to care for survived the influenza. However, "It was thought Bertha had double pneumonia and died in about 10 days." Her body was brought back and she was buried in the cemetery of Salem Church, which is west of Steinauer. Larry adds, "Adelaide Rucker Gyhra related her memory of watching the horse drawn hearse travel through town from Cold Point School area on the way to the cemetery."

That same month, Table Rock lost 23-year-old Dale Main. He and his wife Eva, married only a year, had been in Table Rock only two weeks. He was the night clerk at the new Lincoln Hotel, at the southeast corner of the Square. Dale and Eva were sick in the same bed. He died, she survived. The Argus reported that Eva had no relatives near, and the death of her husband while she was so ill “placed her in a most pathetic position,” although “kindly hands did all that was possible.” Eva had sent her husband’s body to their hometown of Spirit Lake, Iowa. Once she had recovered, she also went there.

On October 31, the Republican reported that 31-year-old Frank Tlustos of Dubois had died at Ft. Riley. So did 28-year-old Harry Farno, who had grown up to Pawnee City and moved away only a few years before after his father died. He was remembered as having a “thoughtful turn of mind. He was a great reader. It was only in intimate conversation with him that one discovered the great depth of his knowledge.” Frank Petrasek of Table Rock was sick at Camp Manhattan and his father John had gone to see him. Wesleyan University student Marie Wilson came home because Creighton University, where she had been going to school, was closed.

It is said that influenza struck “suddenly and severely. Victims suffered greatly. “Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of extreme fatigue, fever, and headache, victims could start turning blue. They would cough with such force that some even tore their abdominal muscles. Foamy blood exited from their mouths and noses. A few bled from their ears. Some vomited; others became incontinent.” Most recovered. Some died within hours or days, often from pneumonia, a common complication.

Obrist's father wrote in his old age about what it was like. Charles F. Obrist wrote in 1991 about what it was like when the flu hit his hometown of Steinauer. He recalled that if pneumonia set in, there was a high fever for about three weeks followed by a crisis. Either the patient recovered, or he got pneumonia in both lungs and died before much longer. Steinauer's doctor, Dr. James Pendergarst, "went day and night" to care for patients. "He even had other men drive him from the livery barn (rented horses) so he could sleep between patients. " The medical care provided, he said, was to address the congestion of the lungs. "To try to clear the lungs, they used mustard plasters and steamed the patients with a sheet over an old umbrella. They then tried to blow medicated steam

from a tea kettle on a sterno heater, like a fondue heater or alcohol lamp."

Charles Obrist of Steinauer recalled that the influenza was widespread. "It was like a plague," he said.He remembered, "Whole families got it and the neighbors would come to do chores, haul hay, deliver groceries or medicine, but not to risk going into the house."

In November, at Pawnee City, people were ill but recovering.

Many at Table Rock were sick. The list of sick includes six at McCourtney, two at John Heers, the Norris Aylor children, Roscoe Zink and agent Beck. However, “nearly every home” had someone with symptoms. Even after the state ban against gatherings lifted, “churches, schools, pool halls, and other places of public gathering” remained closed at Table Rock.

Table Rock received news of another death. Ralph Fisher, age 22, had died two weeks before. He was a Navy pharmacist’s mate on the famous Red Cross hospital ship, Mercy. His cousin Ada Fisher had died within a week of him; she was a nurse in Lincoln and had been due to go active with the Red Cross on November 1.

And people distant from the county continued to suffer. The Pawnee Chief reported that Allen Williamson of the Pawnee City Rock Island Station had been pulled to take charge of the station at Smith Center, Kansas, where the entire force was down. The Schubert school had been closed for a week and would remain closed for another five.

In November, 35-year-old W. F. August Bartels of Steinauer died, leaving a wife and five children at home. Bartels had not been considered dangerously sick. Then pneumonia set in. Fred Albers, Sr. (he was called Fritz), died, too. He was the oldest victim, in his 60s, and had suffered a paralytic stroke the year before.

At Steinauer, Miss Ethelwyn Bacus, a popular principal and teacher at their school, died. She was “loved by her pupils and by her cheery disposition and good nature and pleasant smile.” She had two brothers serving in the military “over there.” It was November 15, and she was 28 years old. She is buried at St. Mary's Church cemetery in Nebraska City. Lawrence Obrist found a comment in the Nebraska Teacher, Vol. 21, p. 280, that Lt. Muron Shrader, recently discharged from the service overseas, was elected the Principal to fill Miss Bacus's position.

Table Rock people continued to die in November. 26-year-old Jeptha (Jeff) Carter, who was “always kind and generous to everyone,” died. One day, two died in the same house, 29-year-old Wesley Loe, a young married man, and Dorris Frasier, a three-year-old boy.

By Thanksgiving, although many were still sick, like Charlie Harlow, who was on crutches for quite some time after he recovered, the influenza seemed on the wane. The “closing up order” was lifted. Table Rock breathed a sigh of relief.

The Republican reported that influenza was still in the county but was “not serious” in Pawnee City.

Two days after Thanksgiving, the hurricane of influenza reversed direction and slammed back into the town harder than ever. The Republican reported that it had come back “raging violently” and it seemed that the entire town of Table Rock was sick, many seriously. All of the C. S. Smith family were sick, all of the Cordell family were sick, all of the Shawhan family were sick, all of the Harry Freeman family but Harry were sick, Mr. and Mrs. Jess Price were sick, and 18-year-old Vern Talbot was sick. Miri Shepherd, age 20, was sick.

Of a sudden, lovely Irene Freeman, age 20, was dead. She had been at her teaching job, in Burchard, and caught sick and come home to Table Rock to be cared for. She had been “loved by all who knew her.” And 51-year-old Mary Bowen Davis mother of six, who had a “sunny, cheerful disposition,” died.

The people of Table Rock were asked to be “brave, watchful, and careful.” Ministers were asked to help Dr. McCrea, who was overwhelmed.

The Argus continued to report on some of the sick. The Frank Johnson family was the largest to be ill, with mother and all ten children bedridden and only Mr. Johnson to care for them. The Argus reported, “Drastic measures to prevent its further spread have been promulgated by the village board.”

In December five more died in Table Rock, including three who had before been named as being ill.

18-year- year-old Vern Talbot, who had graduated from Table Rock just that Spring, died. He had come home sick from his job with the CB&Q.

19-year-old Miri Shepherd, son of the proprietors of the grand Hotel Murphy, died.

39-year-old brickyard worker Evert Cordell died, a “kind and affectionate” husband and father of two.

And under poignant circumstances, the Argus reported that “two bodies are lying cold in death in lower town.” Lewis Chillin and Mary Rubis, ages 30 and 18, had died in the same house within an hour of each other. They were engaged and, indeed, had they lived, they would have been married by the time the paper reported their story. Lewis’s family came and took his body back to Denver. Mary’s father came from Montana but could not afford to take her body; she was buried in the Table Rock Cemetery in one of many now unmarked, unknown graves.

In December, at Mayberry, Heinrich and Louise Bartels lost two of their children, 19-year-old Adolph and 14-year-old Viola. Four children survived, with the last, William Bartels, dying in 2012.

And 20-year-old Jesse Roberts from somewhere on the west side of the county died of pneumonia following influenza. Two of his siblings were reportedly “low and not expected to live.”

Elsewhere, the news quieted down. The Republican reported that Mrs. Gartner who had helped with sick folks at Lon Peacock’s home came home with the influenza Tuesday, but elsewhere around the county besides Table Rock and Steinauer there was no mention. Columns for Cold Point, Frog Pond, Lewiston, Violet were silent about it.

In mid-December, the Republican reported that influenza was still in the county but was “not serious” in Pawnee City. Nevertheless a few days later Pawnee City lost Dr. William T. Johnson, an indirect victim of influenza. He died of a heart attack as he tried to get his car out of the mud of a country road. Two colleagues were serving in the military in France and he had tried to take care of the incredible number of sick people alone and “scarcely had any rest. A body can stand just so much and not more,” said the Republican.

In Burchard just before Christmas, a columnist wrote, “This part of the city has been having a siege of the flu. Nearly everyone has it or has had it. A number are dangerously ill.” However, no one died in Burchard.

In Table Rock, J. S. Price and Ralph Bowen were recovering from a “severe attack” and Sydney Horton was “terribly ill.” The body of little Annabel Wheeler was brought from her home in St. Joe to be buried in Table Rock next to her father.

The Republican reported that Table Rock observed Christmas Day “quietly.” Over 250 people in Table Rock had been taken ill since the onset but now most were recovering. The Argus reported the disease “has had its run with us” and the ban would be lifted the next week, “except as to public dances.” It added, “This does not mean people should become careless.”

Two more deaths occurred in the county before influenza departed. “Sadness filled the hearts of Dubois” when 29-year-old Luella Ward died two days after Christmas of pneumonia following influenza. She left a husband and three children under the age of 5. On January 3, the last death occurred: 28-year-old Bessie Irwin died. She had graduated from Table Rock ten years before and photographs showed a beautiful bright-eyed girl.

Others remained quite ill: Bessie Irwin's husband Earl and their daughter Bernice, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hastings, Mrs. and Mrs. Joe Wopata and daughter Alice, Mrs. C. H. Brock, Frank Kovanda, and Mrs. Cherry and son Clifford. All recovered. The last known death from influenza was that of 18-year-old Ralph Skillet, who had moved to Baileyville, Kansas.

In a medical study about the genetic structure of the gene, reported in the medical Journal of Virology, it was said that the pandemic “remains the most devastating single pandemic of any infectious disease in recorded history. The virus pandemic spread globally, infecting 25 to 30% of the world's population and killing at least 20 to 50 million worldwide, including over 500,000 in the United States.”

There is no list for Pawnee County, but I come up with 25 dead, including those serving in the military. The population of Pawnee County was then about 10,000 (more than three times its current number). The number of dead amounted to far less than the world average of up to 5% dead, which would have had 500 fatalities here. One can only imagine the number of dead in other places to put the statistical number so high.

What would happen if the virus of 1918 time traveled to today? Scientists have considered that question even as they have done their best to produce vaccinations for the virus strains expected each season. Even though there are more drugs available today and more medical technology, they fear that the number of illnesses would likely overwhelm the medical care system just as it did 100 years ago. Hospitals and manufacturers keep only so much on stock. The 1918 influenza hit hard, killing most of its victims within a few months month so could enough be produced and in the hands of care providers in time to make a difference? And would enough care providers avoid influenza to be able to care for all those victims?

It was 100 years ago. If we were sitting in those days of October through December, we would be talking about mostly young people in their 20s and 30s dying within days of a fierce disease as their loved ones stood helplessly by them. It was a bad time. It could happen again.

some sources

|

From Lawrence Obrist, comes a transcript of the memories of his father Charles F. Obrist (1906-1993) (at left circa 1993, from Lawrence's Facebook page). Lawrence says that this is the flu as his dad remembered it in 1991. "It gives you a flavor of how bad real life was then while hoping to survive," Obrist says of his father's memories. "He was 12 then."

|

" It was just like a plague. It hit Camp Funston, KS (Ft. Riley). The camp hospital

couldn’t handle them and when they got so bad they were just set outside to die.

Dr. James Prendergast was here in town (Steinauer) and he went day and night.

He even had other men drive him from the livery barn (rented horses) so he could

sleep between patients. It seemed if they got pneumonia, high fever set in for about

three weeks, and then a crisis came. Sometimes to recover or to get it in both

lungs only to live a short time.

To try to clear the lungs, they used mustard plasters and steamed the patients

with a sheet over an old umbrella. They then tried to blow medicated steam

from a tea kettle on a sterno heater, like a fondue heater or alcohol lamp. Whole

families got it and the neighbors would come to do chores, haul hay, deliver

groceries or medicine, but not to risk going into the house.

Writing about the flu brought back some of those terrible days. You know

too well if it was bad in the civilian population, what it would be like in an Army

camp living so close. It seemed that those who could just about live outside

never got it, or never had it so bad."

Charles F. Obrist

Nov. 12, 1991

|

The website of the National Institutes of Health (the "NIH") is a good source for medical research information.

"The Site of Origin of the 1918 influenza Pandemic And Its Public Health Implications. This 2004 article in the medical Journal of Transitional Disease reported an extensive study of the virus's RNA make up. It described the virus in complex technical terms and concluded it “was derived from a swine virus that itself might be a descendent of a distinct avian H1N1 virus.” So one could simplify what the article said by saying that it was a swine flu that was complicated by a bird flu. |

|

"Origin of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus as studied by codon usage patterns and phylogenetic analysis." This 2011 article in the medical journal RNA is posted on the website of the National Institutes of health. "The pandemic of 1918 was caused by an H1N1 influenza A virus, which is a negative strand RNA virus; however, little is known about the nature of its direct ancestral strains." The article describes research in yet another exploration of the virus.

|

|

Another study about the genetic structure of the virus was reported in the medical Journal of Virology. The study said, it was said that the pandemic “remains the most devastating single pandemic of any infectious disease in recorded history. The virus pandemic spread globally, infecting 25 to 30% of the world's population and killing at least 20 to 50 million worldwide, including over 500,000 in the United States.”

|

|

"Could the deadly 1918 flu pandemic happen again?" by Dennis Thompson, in the Chicago Tribune, February 9, 2018. A good discussion for a lay person.

|

|

Camp Funston image: This image can be found on many internet sites. One place is a website by George Mason University students and faculty relating to biodefense issues.

With the photo is this commentary: "This photo depicts an influenza ward at Camp Funston in Kansas during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. "This flu outbreak occurred between 1918 and 1920 and was one of the most deadly in history, infecting approximately 500 million people and killing 3-5% of the world population (50-100 million.) "That’s killed 3-5% of the entire world–not just infected 3-5% of the world! "Many historical resources cover this worldwise pandemic, also known as “Spanish Flu”, its effects, it causes, and the lasting legacy. Two include flu.gov and John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza." |

On the Historical Society's Facebook page, Ken Dolezal commented on the pandemic, asking if it were true that more soldiers died of influenza than in combat. Lawrence Obrist responded with a quote:

"American combat deaths in World War I totaled 53,402. But about 45,000 American Soldiers died of influenza and related pneumonia by the end of 1918. |