in memory of clarence e. morton

1920 - 1942

taken prisoner by the japanese

at the surrender of corregidor

died in a prisoner of war camp in northeast china

|

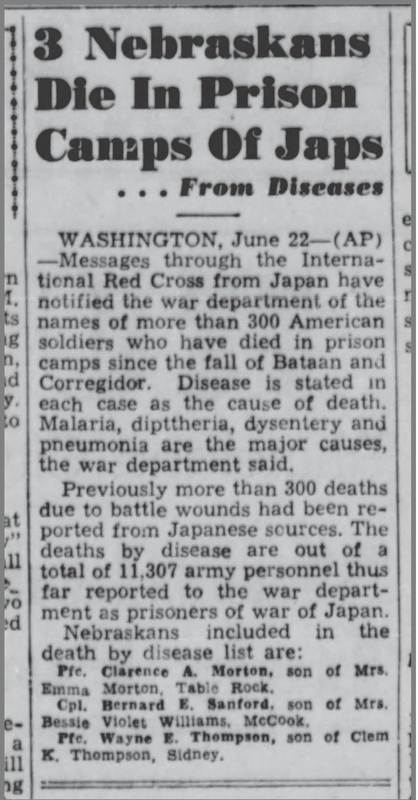

In 1949, the Table Rock Post Office received and delivered a parcel addressed to “Joseph B. Morton, Table Rock, Nebraska.” Inside was a flag folded to fit the box. The flag is still in that same box. It does not appear that it has ever been unfolded. It is likely that Joe Morton or his wife Emma even removed it from the box. With it is a printed form. It said that Clarence’s remains had been interred at a military ceremony in Manila with customary military services over the grave. That cardboard box carries with it the sort of story told by the parents of over 400,000 American service men and women who never returned from the fronts of World War II. In May 1942, Joe and Emma received a letter from the War Department. The letter advised that Clarence was either dead or a prisoner of the Japanese and the War Department would let her know if he showed up on any list of prisoners that the Japanese might eventually provide. Clarence was 22 year old. The letter explained that the War Department did not know who had died and who had been taken prisoner, “In the last days before the surrender of Bataan there were casualties which were not reported to the War Department. Conceivably, the same is true of the surrender of Corregidor….” Clarence was to be considered MIA until more definite information was received. Clarence had arrived at Corregidor on April 21, 1941. It was the largest of four islands protecting the mouth of Manila Bay, under the management of |

of General Douglas MacArthur. Corregidor had been fortified prior to World War I with powerful coastal artillery to which Clarence was assigned. He was in Battery 7 of the 60th Coast Artillery, which was an anti-aircraft artillery unit.

On arrival, Clarence had written a letter home, on the back of a form letter given the soldiers for notifying their family of arrival and providing some information about how to reach them, the island, and their duties. Clarence’s unit fired anti-aircraft machine guns which were water cooled and operated by a small crew the men of which were trained in all positions. The nature of tracer bullets was described and the guns had an “extremely high rate of fire, between 500 and 600 rounds per minute.”

In Clarence’s letter of April 1941, he wrote about the trip across the ocean, boasting that he had not been sea sick. “It made me laugh to see all the boys run for the rail, and boy did they go to it. Just imagine 2200 boys and half of them sick and hanging over the rails.” He wrote about his drill sergeant on Corregidor, who warned them that he would soldiers of them or leave. He wrote about how beautiful Corregidor was, “You cannot imagine how beautiful it is unless you could see it.” He asked for letters from home, joking that he needed them “so that I can hear I am still part of the family even if I am on the other side of the world.” And he asked his folks to “tell Elsie Lou to drop me a line because I want to ask her about someone I wrote to and got no answer from yet.”

On December 29, 1941, the Japanese attacked the islands with a ferocious aerial bombardment. One can only imagine the intensity with which Clarence manned his anti-aircraft artillery post. The defenders – both American and Philippine troops – fought desperately for months. On Corregidor, as the defenders were pounded by bombs carrying 365 tons of explosive over the duration, they lived on about 30 ounces of food a day and with little water. In March 1942, General MacArthur escaped, making his way to Australia where he gave the famous speech in which he declared, “I came through and I shall return.”

In May 1942, came the end. The nearby island of Bataan had just been surrendered, with 76,000 American and Philippine prisoners of war taken by the Japanese. Those prisoners had included Ronald Boston, who had graduated from Table Rock in 1934 and who would survive the Bataan Death March but not the war.

A week after the surrender of Bataan, General Wainwright on Corregidor sent a radio message to FDR saying, “There is a limit of human endurance and that point has long been passed.” The following day, Clarence Morton of Table Rock, Nebraska, became one of about 11,000 prisoners of war – soldiers and civilians, Americans and Filipinos.

A year later, in May of 1943, Joe and Emma received another letter from a general in the War Department. Clarence was still MIA. The letter closed, “I regret that the far-flung operations of the present war, the ebb and flow of combat over great distances in isolated areas, and the characteristics of our enemies, impose upon us this heavy burden of uncertainty with respect to the safety of our loved ones.”

Then Joe and Emma learned that Clarence had died in a prisoner of war camp. Weeks later, a telegram came, a document handled and rehandled, and probably wept upon, until it is wrinkled and soft. It reported that Clarence had died on May 11, 1943, shortly before the telegram was sent. “The Secretary of War shares your grief and sends his deep sympathy. Letter follows.”

How carefully Joe and Emma must have searched the memories for what they had been doing only weeks before on the day that Clarence lay dying on the other side of the world. However, in the letter that followed, even that amount of certainty was taken away. It advised that they did not know when he had died. The date they had given was the date they had received the report of his death.

Finally, in October 1945, over two years after Joe and Emma learned of Clarence’s death, came a letter telling them that Clarence had actually been dead since August 30, 1942, only three months after the surrender of Corregidor. Unknown to them at the time, Clarence had been moved by the Japanese to a prison camp in the northeast of China, near the city of Shenyang.

Finally, in 1949 there came the cardboard box.

After that the mailbox caused only more pain. Grandson Leroy Malmos of Superior, Nebraska recalls hearing that there was a life insurance policy which was paid to Emma in several installments, coming by letter. “My mother told me that every time Grandma found a letter in the mailbox from the War Department, it was like losing Clarence all over again.”

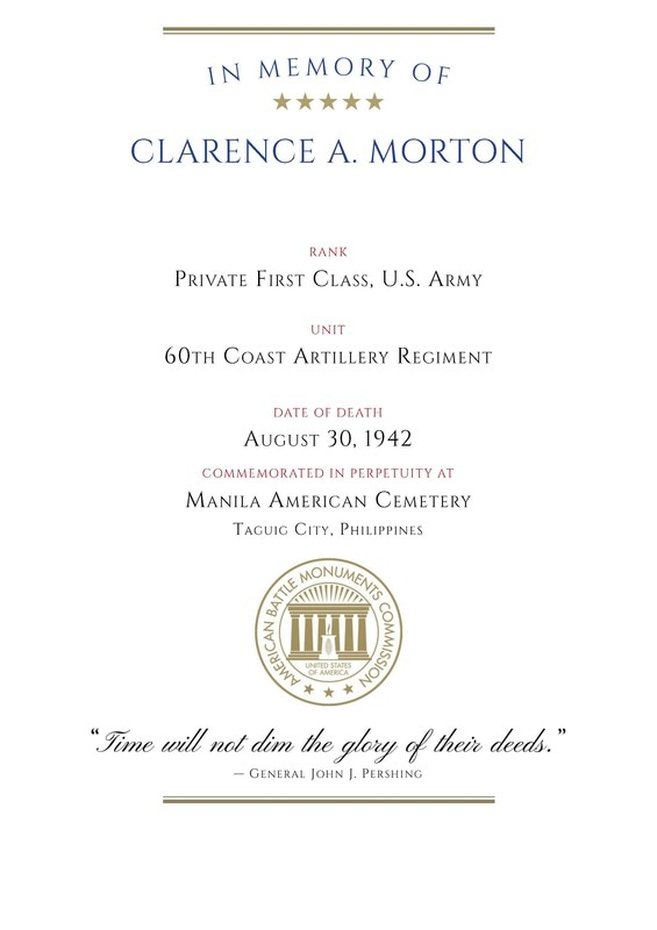

There is a tombstone for Clarence at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Manila in Plot D, Row 10, Grave 77. His remains may be buried there, but more likely the tombstone states “In Memory of” Clarence E. Morton and his body lies in a place now known but to God. The cemetery reportedly has the largest number of graves of any cemetery for U.S. personnel killed during World War II.

Joe died in 1955, Emma in 1980. They had three other children. Their son Herman of Table Rock died in 1988, their daughter Millie a year later, and their son Louis in 2003.

Clarence’s flag and documents including the letters above, and the telegram notifying Joe and Emma of Clarence’s death, were recently donated to the Table Rock Historical Society. Their grandson Leroy Malmos, Millie’s son, had safeguarded them for many years. After visiting the Historical Society’s Veterans Museum in 2014, Leroy came to the conclusion that it would be an appropriate guardian for these treasures.

To honor him, Clarence’s flag was flown by the Table Rock Historical Society on Memorial Day weekend 2017. Boy Scout Troop 387 of Humboldt raised the flag in a ceremony in front of the Table Rock Veterans Museum on the west side of the Square.

On arrival, Clarence had written a letter home, on the back of a form letter given the soldiers for notifying their family of arrival and providing some information about how to reach them, the island, and their duties. Clarence’s unit fired anti-aircraft machine guns which were water cooled and operated by a small crew the men of which were trained in all positions. The nature of tracer bullets was described and the guns had an “extremely high rate of fire, between 500 and 600 rounds per minute.”

In Clarence’s letter of April 1941, he wrote about the trip across the ocean, boasting that he had not been sea sick. “It made me laugh to see all the boys run for the rail, and boy did they go to it. Just imagine 2200 boys and half of them sick and hanging over the rails.” He wrote about his drill sergeant on Corregidor, who warned them that he would soldiers of them or leave. He wrote about how beautiful Corregidor was, “You cannot imagine how beautiful it is unless you could see it.” He asked for letters from home, joking that he needed them “so that I can hear I am still part of the family even if I am on the other side of the world.” And he asked his folks to “tell Elsie Lou to drop me a line because I want to ask her about someone I wrote to and got no answer from yet.”

On December 29, 1941, the Japanese attacked the islands with a ferocious aerial bombardment. One can only imagine the intensity with which Clarence manned his anti-aircraft artillery post. The defenders – both American and Philippine troops – fought desperately for months. On Corregidor, as the defenders were pounded by bombs carrying 365 tons of explosive over the duration, they lived on about 30 ounces of food a day and with little water. In March 1942, General MacArthur escaped, making his way to Australia where he gave the famous speech in which he declared, “I came through and I shall return.”

In May 1942, came the end. The nearby island of Bataan had just been surrendered, with 76,000 American and Philippine prisoners of war taken by the Japanese. Those prisoners had included Ronald Boston, who had graduated from Table Rock in 1934 and who would survive the Bataan Death March but not the war.

A week after the surrender of Bataan, General Wainwright on Corregidor sent a radio message to FDR saying, “There is a limit of human endurance and that point has long been passed.” The following day, Clarence Morton of Table Rock, Nebraska, became one of about 11,000 prisoners of war – soldiers and civilians, Americans and Filipinos.

A year later, in May of 1943, Joe and Emma received another letter from a general in the War Department. Clarence was still MIA. The letter closed, “I regret that the far-flung operations of the present war, the ebb and flow of combat over great distances in isolated areas, and the characteristics of our enemies, impose upon us this heavy burden of uncertainty with respect to the safety of our loved ones.”

Then Joe and Emma learned that Clarence had died in a prisoner of war camp. Weeks later, a telegram came, a document handled and rehandled, and probably wept upon, until it is wrinkled and soft. It reported that Clarence had died on May 11, 1943, shortly before the telegram was sent. “The Secretary of War shares your grief and sends his deep sympathy. Letter follows.”

How carefully Joe and Emma must have searched the memories for what they had been doing only weeks before on the day that Clarence lay dying on the other side of the world. However, in the letter that followed, even that amount of certainty was taken away. It advised that they did not know when he had died. The date they had given was the date they had received the report of his death.

Finally, in October 1945, over two years after Joe and Emma learned of Clarence’s death, came a letter telling them that Clarence had actually been dead since August 30, 1942, only three months after the surrender of Corregidor. Unknown to them at the time, Clarence had been moved by the Japanese to a prison camp in the northeast of China, near the city of Shenyang.

Finally, in 1949 there came the cardboard box.

After that the mailbox caused only more pain. Grandson Leroy Malmos of Superior, Nebraska recalls hearing that there was a life insurance policy which was paid to Emma in several installments, coming by letter. “My mother told me that every time Grandma found a letter in the mailbox from the War Department, it was like losing Clarence all over again.”

There is a tombstone for Clarence at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Manila in Plot D, Row 10, Grave 77. His remains may be buried there, but more likely the tombstone states “In Memory of” Clarence E. Morton and his body lies in a place now known but to God. The cemetery reportedly has the largest number of graves of any cemetery for U.S. personnel killed during World War II.

Joe died in 1955, Emma in 1980. They had three other children. Their son Herman of Table Rock died in 1988, their daughter Millie a year later, and their son Louis in 2003.

Clarence’s flag and documents including the letters above, and the telegram notifying Joe and Emma of Clarence’s death, were recently donated to the Table Rock Historical Society. Their grandson Leroy Malmos, Millie’s son, had safeguarded them for many years. After visiting the Historical Society’s Veterans Museum in 2014, Leroy came to the conclusion that it would be an appropriate guardian for these treasures.

To honor him, Clarence’s flag was flown by the Table Rock Historical Society on Memorial Day weekend 2017. Boy Scout Troop 387 of Humboldt raised the flag in a ceremony in front of the Table Rock Veterans Museum on the west side of the Square.

long in their memories

Clarence was never forgotten. It was a visit to the Veterans Museum by his nephew Lee Malmos that led to a 2017 ceremony raising Clarence's burial flag for the first -- and probably last -- time. When the ceremony was planned, Lee and his wife and Lee's sister Linda planned to attend. Lee asked about his cousin Wayne, who he had not been in touch with for many years, and the Wayne and his sister Elaine were found. Lee & Linda were the children of Clarence's sister Millie. Wayne and Elaine were the children of Clarence's brother Louis. They brought children and grandchildren -- three generations -- to commemorate a young man the memory of whom had been passed tenderly from Joe and Emma.