herman brauer

a fallen soldier worth remembering

This page has been a joint labor of love by both the Table Rock Historical Society and the Steinauer Heritage House, both of whom maintain rolls of honor. As with Lawrence Wilcox, who died in the Korean War, Herman Brauer is "claimed" by both Steinauer and Table Rock, both of whom honor his memory. Table Rock honors him because he is buried in the Table Rock Cemetery. Steinauer honors him because he lived near Steinauer. He died, far from the nightmares of the war in France, at the family farm, 1-1/2 miles east and a mile north of Steinauer. It appears that this was in the Clear Creek township which lies between Table Rock and Steinauer, but considerably closer to Steinauer.

You will not find Herman Brauer on any Gold Star list but ours. He died years after the war, by his own hand.

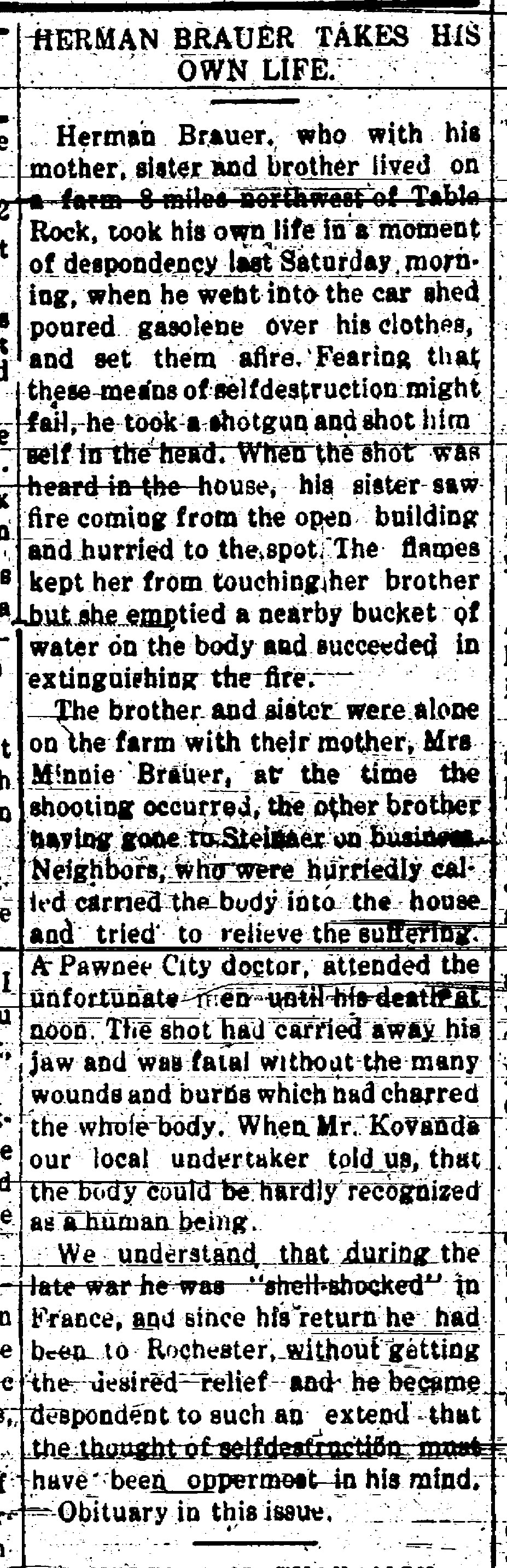

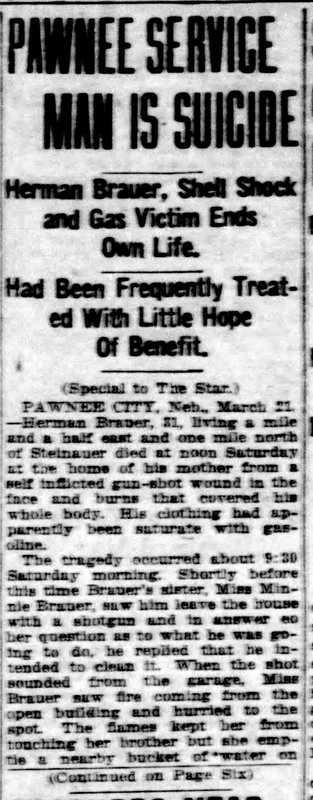

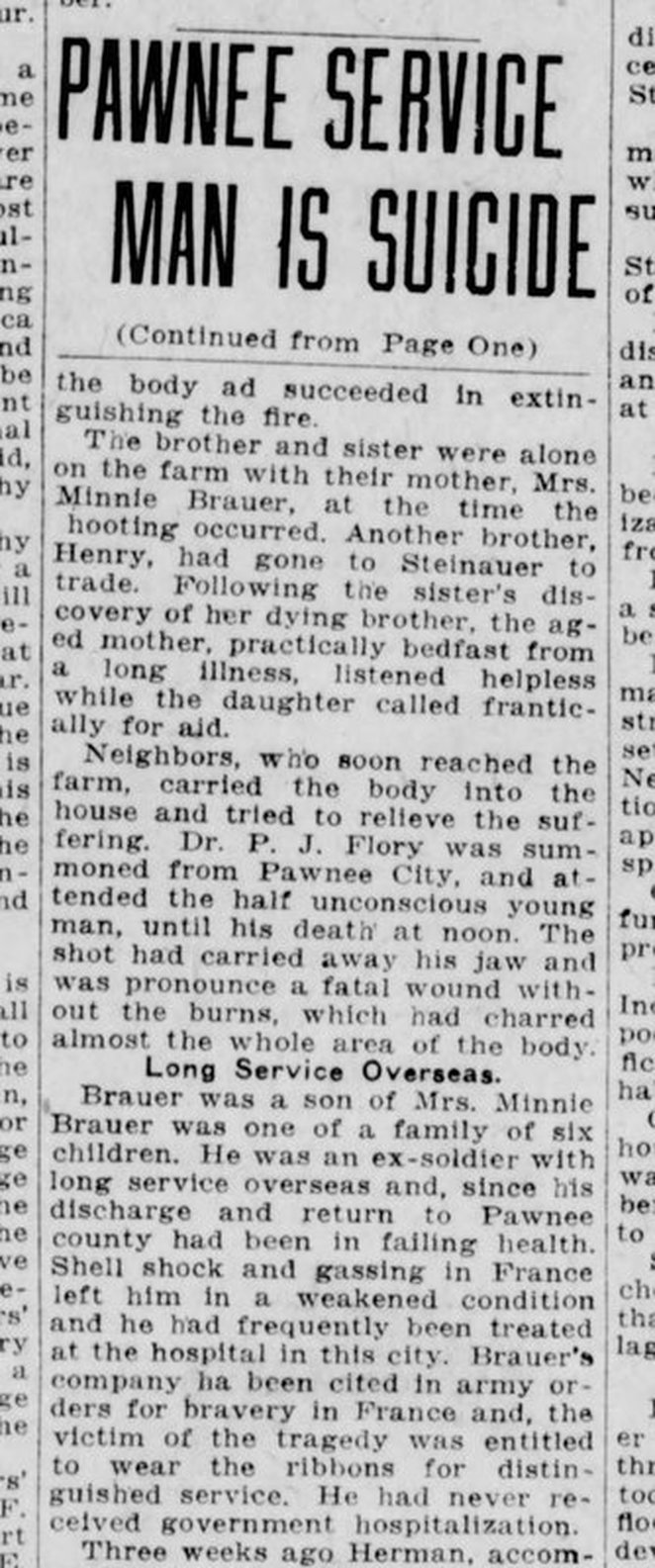

Of the several articles about Herman's death in 1925, the Pawnee Chief was the most comprehensive about the details of Herman's suicide, and also the most emphatic about the link between the Great War and his death. The Chief demanded that Herman be remembered as a man wrecked by the Great War, mentally destroyed by shell shock, physically destroyed by injuries including being gassed and being knocked unconscious for hours.

The Chief's headline:

Of the several articles about Herman's death in 1925, the Pawnee Chief was the most comprehensive about the details of Herman's suicide, and also the most emphatic about the link between the Great War and his death. The Chief demanded that Herman be remembered as a man wrecked by the Great War, mentally destroyed by shell shock, physically destroyed by injuries including being gassed and being knocked unconscious for hours.

The Chief's headline:

WORLD WAR HERO

DIES TRAGIC DEATH AT HOME

HERMAN BRAUER SUCCUMBS TO BURNS AND GUN SHOT WOUND AT HOME NORTHEAST OF STEINAUER SATURDAY --

SUFFERED SHELL SHOCK IN FRANCE

A TRAGIC DEATH

It happened in 1925 on a family farm near Steinauer. There lived Herman Brauer with his widowed mother, a brother, and a sister. On a sunny March day that year, Herman killed himself. He had gone into the house for a shotgun. “Where are you going?” his sister Minnie asked. “To shoot some rats.” He went to a shed, doused himself with gasoline, and then shot himself in the head. Minnie, hearing the single shot and seeing flames shooting from the shed, ran there to find her brother on fire and dying of a head wound. She called neighbors, who got him to the house, where he lived several hours more.

Before the Great War, Herman was or wanted to be a veterinarian, according to Shelly McClintock, whose grandma Adaline Brauer McClintock was Herman's sister. But off Herman went "over there," and he had come home suffering from shell shock and from conditions causing unrelenting physical pain as well. He had even been to see the famous Mayo brothers in Rochester, Minnesota. Shell shock was well known by that time, although early in the War it had been little understood. It was at first thought to have been tied to head injury caused by the shock of exploding shells. It is now called combat stress reaction, a type of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The Pawnee Chief newspaper’s headline was WORLD WAR HERO DIES TRAGIC DEATH AT HOME, with a secondary headline, “Herman Brauer Succumbs to Burns and Gunshot Wound.” The article said that Herman was “universally-known and well liked.” He had endured “harrowing” experiences in the war, including one occasion when only he and another in his company had survived. The French government had decorated him for bravery in action. The Chief asserted that even though Herman had died by his own hand,

It happened in 1925 on a family farm near Steinauer. There lived Herman Brauer with his widowed mother, a brother, and a sister. On a sunny March day that year, Herman killed himself. He had gone into the house for a shotgun. “Where are you going?” his sister Minnie asked. “To shoot some rats.” He went to a shed, doused himself with gasoline, and then shot himself in the head. Minnie, hearing the single shot and seeing flames shooting from the shed, ran there to find her brother on fire and dying of a head wound. She called neighbors, who got him to the house, where he lived several hours more.

Before the Great War, Herman was or wanted to be a veterinarian, according to Shelly McClintock, whose grandma Adaline Brauer McClintock was Herman's sister. But off Herman went "over there," and he had come home suffering from shell shock and from conditions causing unrelenting physical pain as well. He had even been to see the famous Mayo brothers in Rochester, Minnesota. Shell shock was well known by that time, although early in the War it had been little understood. It was at first thought to have been tied to head injury caused by the shock of exploding shells. It is now called combat stress reaction, a type of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The Pawnee Chief newspaper’s headline was WORLD WAR HERO DIES TRAGIC DEATH AT HOME, with a secondary headline, “Herman Brauer Succumbs to Burns and Gunshot Wound.” The article said that Herman was “universally-known and well liked.” He had endured “harrowing” experiences in the war, including one occasion when only he and another in his company had survived. The French government had decorated him for bravery in action. The Chief asserted that even though Herman had died by his own hand,

“He was absolutely unaccountable for his death….He is just as much a hero as those who died in France. His life was given for his country and his death is a result of the war.” |

|

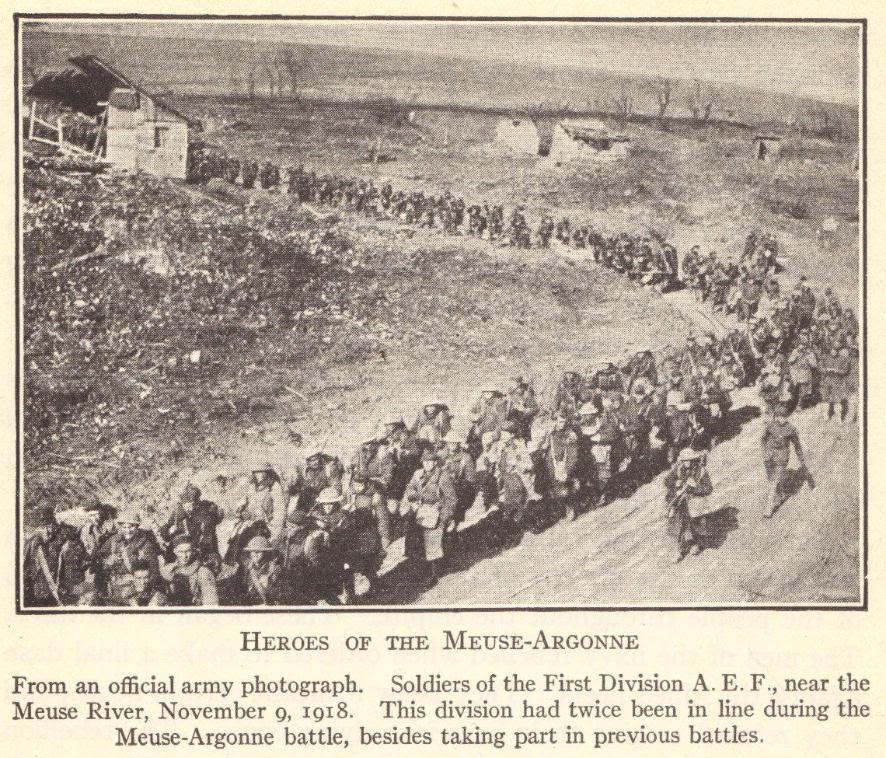

Herman Brauer’s life had begun in 1883. He was one of the seven children of Heinrich and Wilhelmena Brauer. His life as he knew it ended on December 1, 1917 when he set foot in the muddy killing fields of France to face the grinding war of attrition that Europe’s great armies had fought for over three years. He was a soldier in Company A of the 18th Infantry of the American Expeditionary Force, the first Americans to arrive at the Western Front and soon redesignated the First Division but also called the Fighting First and the Bloody First. They eventually wore the patch of the Big Red One. General John J. Pershing – Black Jack Pershing – was their leader.

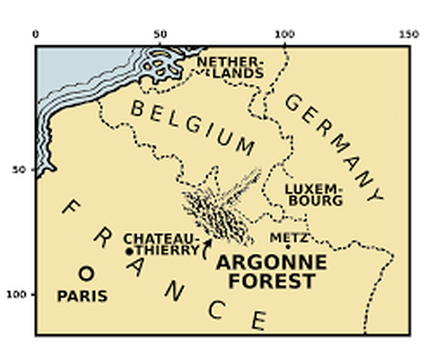

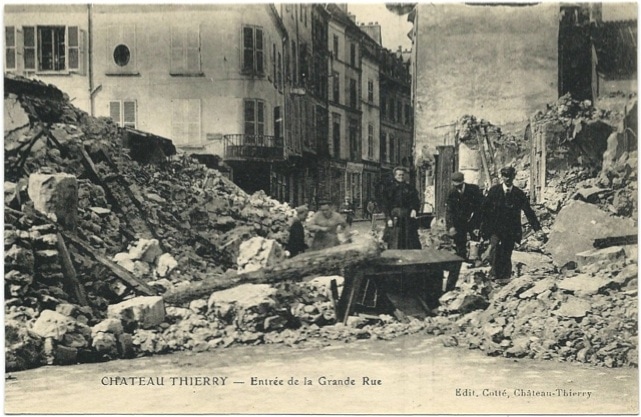

THE SECOND BATTLE OF THE MARNE -- AT CHATEAU-THIERRY After months of minor engagements at places like Picardy, Pershing sent the Division, including Herman, to the Marne River valley, where his unit was placed in the trenches at Chateau-Thierry, a town on the Marne River east of Paris. The battle-hardened Germans immediately launched an offensive. It was July 1918 by that time and the three-week Second Battle of the Marne was about to begin. The Americans hunkered down for three days as everything plus the kitchen sink was thrown at them. It was reported that on one occasion Herman was without food or water for three days and because of a constant day-and-night bombardment of artillery could not move. Only he and another in his company were left alive. That may have coincided with this three day assault at Chateau-Thierry. In the early morning of the fourth day, a counter-assault began with a rolling barrage, a synchronized wall of artillery fire that began near the American lines and moved forward at the rate of 100 yards every two minutes. Behind that creeping wall, the troops went “over the top” and advanced with it despite heavy casualties. Finally, as one history described it, the two opposing lines “inter-penetrated and individual American units exercised initiative and continued fighting despite being nominally behind enemy lines.” THE BATTLE OF ST. MIHIEL - AN UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPT TO SECURE METZ The month after Chateau-Thierry, the 18th Infantry joined in a the major battle of St. Mihiel, an unsuccessful attempt to secure the city of Metz. Pershing had both his own Division and over 100,000 French troops under his command, and the U. S. Army Air Service played a significant part. The attack caught the Germans in the act of retreating, so that their artillery was out of place and their forces unorganized. However, the attack faltered as artillery and food supplies were left behind on the muddy roads, demonstrating the difficulty of supplying massive armies that were on the move. That gave the Germans time to reorganize and defend. The battle was lost. Still, it established credibility for the Americans. THE BATTLE OF MEUSE-ARGONNE - MORE AMERICAN FIGHTING MEN THAN IN ANY BATTLE IN HISTORY It was the last major battle of the War that is best known in military histories. It was fought in the Meuse-Argonne Forest in October 1918. One of the objectives was to strike for the rail hub in Sedan, in the Verdun area. Again, Herman with the 18th Infantry was there – as well as about every other American soldier. It involved, some say, as many as 1.5 million American soldiers, the largest concentration in American history. The battle stretched across the entire 440-mile Western front. Scenes of this battle show a devastated landscape with little left but mud and stumps of trees. How it became that way is told by an officer of the 18th named Lt. Maury who took command after his superior was killed. He was not with Herman’s company, but the experience was probably similar. He wrote that upon taking command, |

There was not a single sergeant. We literally lost each other. There were no bugles, no flags, no drums and, as far as we knew, no heroes. The great noise was like great stillness, everything seemed blotted out. We hardly knew where the Germans were. We were simply in a big black spot with streaks of screaming red and yellow…The intensity of it simply enters your heart and brain and tears every nerve to pieces. Although so many men had been killed, there was nothing to do but keep on going. |

|

The battle of Meuse-Argonne cost almost 27,000 American lives and over 28,000 German lives and was the bloodiest battle of the war.

THE BATTLE OF SEDAN -- CUTTING OFF GERMAN RAIL SUPPORT After Meuse-Argonne, the 18th Infantry joined a successful battle to reach the rail hub at Sedan. This was the farthest penetration into enemy territory by the Americans. They were there when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. THE HUMAN COST OF WAR One source reports that by War’s end, out of the First Division’s complement of about 27,000 men, almost 5,000 had been killed in action, another 1,000 had died of their wounds or were missing, and about 17,000 were wounded. Herman Brauer came home – a victim of shell shock and of mustard case, too, it was said. He was wrecked physically and mentally but he came home. |

HERMAN BRAUER -- ONE OF OURS

Herman belonged to the Table Rock Odd Fellows Lodge, from whom his pallbearers were chosen, and his funeral was held at the Table Rock Methodist Church. He belonged to the Pawnee City American Legion Post and to the Masonic Lodge at Elk Creek. He lived near Steinauer when he died.

He belonged to all of us in this County, and at the time of his death he was “universally known and well liked” yet as the 100th year of war’s end neared, no one had remembered him or his life. I “found” him about a year ago as I was reading the county papers while researching another subject.

It is ironic that Herman Brauer died by his own hand after watching so many others fall on the battlefields of France.

It is ironic that he died on a quiet farm after having survived a battle in which the “great noise was like great stillness, everything seemed blotted out,” in a battle so intense that it “enters your heart and brain and tears every nerve to pieces,” as Lt. Maury so vividly wrote.

As the Pawnee Chief said, it was a tragic death. Such is the way of war to this day.

So here’s to Herman Brauer, a forgotten hero and the last Pawnee County casualty of the Great War. May he rest in peace.

Herman belonged to the Table Rock Odd Fellows Lodge, from whom his pallbearers were chosen, and his funeral was held at the Table Rock Methodist Church. He belonged to the Pawnee City American Legion Post and to the Masonic Lodge at Elk Creek. He lived near Steinauer when he died.

He belonged to all of us in this County, and at the time of his death he was “universally known and well liked” yet as the 100th year of war’s end neared, no one had remembered him or his life. I “found” him about a year ago as I was reading the county papers while researching another subject.

It is ironic that Herman Brauer died by his own hand after watching so many others fall on the battlefields of France.

It is ironic that he died on a quiet farm after having survived a battle in which the “great noise was like great stillness, everything seemed blotted out,” in a battle so intense that it “enters your heart and brain and tears every nerve to pieces,” as Lt. Maury so vividly wrote.

As the Pawnee Chief said, it was a tragic death. Such is the way of war to this day.

So here’s to Herman Brauer, a forgotten hero and the last Pawnee County casualty of the Great War. May he rest in peace.

what did herman experience in france? REDUX & MORE DETAILS

We don't know what happened to him with any specificity. Some of the larger picture -- the role of his Division and his infantry unit give some hints. They were involved in more than one major battle, even though American forces did not enter the war until it had been ongoing for several years. The fact that his infantry unit was awarded two medals by the French government -- the Croix de Guerre -- offers another hint.

The following small summary of the war pieces together military history as specific to Herman's unit as possible. Source links follow it.

America entered the Great War in April 1917. In June 8, the Army established a unit to fight in France, the First Expeditionary Division. The first units sailed for France within the week, with the remainder of the Division arriving in France by Christmas.

General John J. Pershing, known as Black Jack Pershing, was at their head, and his first order of business was to save Paris from invasion.

Part of the Division was sent to march in the streets of Paris to bolster the sagging spirits of the French. The famous words, “Lafayette we are here,” were uttered at Lafayette’s tomb, referring to the Americans paying the debt of Lafayette’s leadership in bringing important French military support to the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

The other part of the Division, including the 18th Infantry in which Herman served, was sent to the valley of the Marne River valley to fight in the last major engagement of the war, Aisne-Marne (also known as Bealleau). It lasted from July 15 to August 8, 1918. The Marne advance was one of the Amerians’ three initial battle objectivers – Marne, Amiens, and St. Mihiel. The theater of operations ran from Chateau-Thierry to a point north of St. Mihiel. Herman’s obituary says that he fought at Chateau-Thierry, which was part of the Aisne-Marne campaign.

The Battle of Château-Thierry was fought on July 18, 1918 and was one of the first actions of the American Expeditionary Forces under General John J. "Black Jack" Pershing, a graduate of the University of Nebraska Law School. It was part of the Second Battle of the Marne, initially prompted by a German offensive launched on 15 July against the American Expeditionary Force.

Chateau Thierry had a 25 mile front. A military history of the 18th Infantry says, “The allied forces had managed to keep their plans a secret, and their attack at 04:45 took the Germans by surprise when the troops went "Over the Top" without a preparatory artillery bombardment, but instead followed closely behind a rolling barrage which began with great synchronized precision. Eventually, the two opposing assaults (lines) inter-penetrated and individual American units exercised initiative and continued fighting despite being nominally behind enemy lines.”

Following the Aisne-Marne battle, Black Jack Pershing led the St. Mihiel forces, which again included the 18th infantry into battle St. Mihiel, from September 11-13, 1918.

The last major World War I battle was fought in the Meuse-Argonne Forest. The Division advanced seven kilometers and defeated, in whole or part, eight German divisions. This action cost the 1st Division over 7600 casualties. The fighting in the Argonne forest are especially well known for photographs of huge areas where the artillery fire turned the landscape into an eerie and endless area of trees fractured to the stumps, with not a living plant left.

The Americans then crossed the Rhine River into Germany. At Sedan was the farthest penetration of the Americans, where they were located when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Again, the 18th Infantry in which Herman served was included in the battle to reach Sean.

The First Division deployed back to the United States in August and September of 1919. By that time, the Division had suffered 22,668 casualties, had boasted five Medal of Honor recipients, and carried campaign streamers that included Montdidier-Noyon, Aisne-Marne; St. Mihiel; Meuse- Argonne; Lorraine1 917; Lorraine, 1918; and Picardy, 1918.

The 18th Infantry participated in the following battles: Mondidier-Noyon, Aisne-Marne, St.Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne, Lorraine (both 1917 and 1918), and Picardi 1918.

The French government awarded honors, the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, for their role in Aisne-Marne and Meuse-Argonne.

General John J. Pershing, known as Black Jack Pershing, was at their head, and his first order of business was to save Paris from invasion.

Part of the Division was sent to march in the streets of Paris to bolster the sagging spirits of the French. The famous words, “Lafayette we are here,” were uttered at Lafayette’s tomb, referring to the Americans paying the debt of Lafayette’s leadership in bringing important French military support to the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

The other part of the Division, including the 18th Infantry in which Herman served, was sent to the valley of the Marne River valley to fight in the last major engagement of the war, Aisne-Marne (also known as Bealleau). It lasted from July 15 to August 8, 1918. The Marne advance was one of the Amerians’ three initial battle objectivers – Marne, Amiens, and St. Mihiel. The theater of operations ran from Chateau-Thierry to a point north of St. Mihiel. Herman’s obituary says that he fought at Chateau-Thierry, which was part of the Aisne-Marne campaign.

The Battle of Château-Thierry was fought on July 18, 1918 and was one of the first actions of the American Expeditionary Forces under General John J. "Black Jack" Pershing, a graduate of the University of Nebraska Law School. It was part of the Second Battle of the Marne, initially prompted by a German offensive launched on 15 July against the American Expeditionary Force.

Chateau Thierry had a 25 mile front. A military history of the 18th Infantry says, “The allied forces had managed to keep their plans a secret, and their attack at 04:45 took the Germans by surprise when the troops went "Over the Top" without a preparatory artillery bombardment, but instead followed closely behind a rolling barrage which began with great synchronized precision. Eventually, the two opposing assaults (lines) inter-penetrated and individual American units exercised initiative and continued fighting despite being nominally behind enemy lines.”

Following the Aisne-Marne battle, Black Jack Pershing led the St. Mihiel forces, which again included the 18th infantry into battle St. Mihiel, from September 11-13, 1918.

The last major World War I battle was fought in the Meuse-Argonne Forest. The Division advanced seven kilometers and defeated, in whole or part, eight German divisions. This action cost the 1st Division over 7600 casualties. The fighting in the Argonne forest are especially well known for photographs of huge areas where the artillery fire turned the landscape into an eerie and endless area of trees fractured to the stumps, with not a living plant left.

The Americans then crossed the Rhine River into Germany. At Sedan was the farthest penetration of the Americans, where they were located when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Again, the 18th Infantry in which Herman served was included in the battle to reach Sean.

The First Division deployed back to the United States in August and September of 1919. By that time, the Division had suffered 22,668 casualties, had boasted five Medal of Honor recipients, and carried campaign streamers that included Montdidier-Noyon, Aisne-Marne; St. Mihiel; Meuse- Argonne; Lorraine1 917; Lorraine, 1918; and Picardy, 1918.

The 18th Infantry participated in the following battles: Mondidier-Noyon, Aisne-Marne, St.Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne, Lorraine (both 1917 and 1918), and Picardi 1918.

The French government awarded honors, the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, for their role in Aisne-Marne and Meuse-Argonne.

Additional sources:

http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0018in001bn.htm

Chateau-thierry monument: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau-Thierry_American_Monument

Meuse Argonne: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meuse-Argonne_Offensive

sedan, france: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedan,_Ardennes

http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0018in001bn.htm

Chateau-thierry monument: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau-Thierry_American_Monument

Meuse Argonne: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meuse-Argonne_Offensive

sedan, france: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedan,_Ardennes

shell shock

|

By the end of World War I, as shell shock received more attention, "the majority of shell shock cases were perceived as emotional collapse in the face of the unprecedented and hardly imaginable horrors of trench warfare. "

In September 1914, at the very outset of the great war, a dreadful rumor arose. It was said that at the Battle of the Marne, east of Paris, soldiers on the front line had been discovered standing at their posts in all the dutiful military postures—but not alive. “Every normal attitude of life was imitated by these dead men,” according to the patriotic serial The Times History of the War, published in 1916. “The illusion was so complete that often the living would speak to the dead before they realized the true state of affairs.” “Asphyxia,” caused by the powerful new high-explosive shells, was the cause for the phenomenon—or so it was claimed. That such an outlandish story could gain credence was not surprising: notwithstanding the massive cannon fire of previous ages, and even automatic weaponry unveiled in the American Civil War, nothing like this thunderous new artillery firepower had been seen before. A battery of mobile 75mm field guns, the pride of the French Army, could, for example, sweep ten acres of terrain, 435 yards deep, in less than 50 seconds; 432,000 shells had been fired in a five-day period of the September engagement on the Marne. The rumor emanating from there reflected the instinctive dread aroused by such monstrous innovation. Surely—it only made sense—such a machine must cause dark, invisible forces to pass through the air and destroy men’s brains. Shrapnel from mortars, grenades and, above all, artillery projectile bombs, or shells, would account for an estimated 60 percent of the 9.7 million military fatalities of World War I. And, eerily mirroring the mythic premonition of the Marne, it was soon observed that many soldiers arriving at the casualty clearing stations who had been exposed to exploding shells, although clearly damaged, bore no visible wounds. Rather, they appeared to be suffering from a remarkable state of shock caused by blast force. This new type of injury, a British medical report concluded, appeared to be “the result of the actual explosion itself, and not merely of the missiles set in motion by it.” In other words, it appeared that some dark, invisible force had in fact passed through the air and was inflicting novel and peculiar damage to men’s brains. “Shell shock,” the term that would come to define the phenomenon, first appeared in the British medical journal The Lancet in February 1915, only six months after the commencement of the war. In a landmark article, Capt. Charles Myers of the Royal Army Medical Corps noted “the remarkably close similarity” of symptoms in three soldiers who had each been exposed to exploding shells: Case 1 had endured six or seven shells exploding around him; Case 2 had been buried under earth for 18 hours after a shell collapsed his trench; Case 3 had been blown off a pile of bricks 15 feet high. All three men exhibited symptoms of “reduced visual fields,” loss of smell and taste, and some loss of memory. “Comment on these cases seems superfluous,” Myers concluded, after documenting in detail the symptoms of each. “They appear to constitute a definite class among others arising from the effects of shell-shock.” Early medical opinion took the common-sense view that the damage was “commotional,” or related to the severe concussive motion of the shaken brain in the soldier’s skull. Shell shock, then, was initially deemed to be a physical injury, and the shellshocked soldier was thus entitled to a distinguishing “wound stripe” for his uniform, and to possible discharge and a war pension. But by 1916, military and medical authorities were convinced that many soldiers exhibiting the characteristic symptoms—trembling “rather like a jelly shaking”; headache; tinnitus, or ringing in the ear; dizziness; poor concentration; confusion; loss of memory; and disorders of sleep—had been nowhere near exploding shells. Rather, their condition was one of “neurasthenia,” or weakness of the nerves—in laymen’s terms, a nervous breakdown precipitated by the dreadful stress of war. Organic injury from blast force? Or neurasthenia, a psychiatric disorder inflicted by the terrors of modern warfare? Unhappily, the single term “shell shock” encompassed both conditions. Yet it was a nervous age, the early 20th century, for the still-recent assault of industrial technology upon age-old sensibilities had given rise to a variety of nervous afflictions. As the war dragged on, medical opinion increasingly came to reflect recent advances in psychiatry, and the majority of shell shock cases were perceived as emotional collapse in the face of the unprecedented and hardly imaginable horrors of trench warfare. There was a convenient practical outcome to this assessment; if the disorder was nervous and not physical, the shellshocked soldier did not warrant a wound stripe, and if unwounded, could be returned to the front. |

In today's world, we have become more sensitive to the illness of post-traumatic stress disorder. It was just being recognized in World War I, when it was called shell shock. That is the term used by the Chief and other newspapers who reported on Herman's death.

In a succinct article in the British Daily Mail, shell shock was well summarized:

Shell shock was a term used during the First World War to describe the psychological trauma suffered by men serving on the war's key battlefronts.

The term was coined, in 1917, by a medical officer called Charles Myers - it was also known as 'war neurosis', 'combat stress' and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

At first shell shock was thought to be caused by soldiers being exposed to exploding shells.

But doctors couldn't find any physical damage to explain the symptoms. Medical staff started to realise that there were deeper causes.

Symptoms:

Hysteria and anxiety

Paralysis

Limping and muscle contractions

Blindness and deafness

Nightmares and insomnia

Heart palpitations

Depression

By the end of the war, more than 80,000 men who had endured the horrors of battle were struggling to return to normality.

At the time, most shell shock victims were treated harshly and with little sympathy as their symptoms were not understood and they were seen as a sign of weakness. In several medical establishments instead of receiving proper care, many victims endured more trauma with treatments such as solitary confinement or electric shock therapy.

In a succinct article in the British Daily Mail, shell shock was well summarized:

Shell shock was a term used during the First World War to describe the psychological trauma suffered by men serving on the war's key battlefronts.

The term was coined, in 1917, by a medical officer called Charles Myers - it was also known as 'war neurosis', 'combat stress' and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

At first shell shock was thought to be caused by soldiers being exposed to exploding shells.

But doctors couldn't find any physical damage to explain the symptoms. Medical staff started to realise that there were deeper causes.

Symptoms:

Hysteria and anxiety

Paralysis

Limping and muscle contractions

Blindness and deafness

Nightmares and insomnia

Heart palpitations

Depression

By the end of the war, more than 80,000 men who had endured the horrors of battle were struggling to return to normality.

At the time, most shell shock victims were treated harshly and with little sympathy as their symptoms were not understood and they were seen as a sign of weakness. In several medical establishments instead of receiving proper care, many victims endured more trauma with treatments such as solitary confinement or electric shock therapy.

Symptoms of shell shock noted during World War I: limping and muscle contractions, "hysteria" and anxiety, nightmares and insomnia, heart palpitations, depression, depression, dizziness and disorientation, and loss of appetite.

Post-traumatic stress disorder has been known since the time of the Greeks, but in World War I was studied more, at which time it was known as "shell shock" and "combat neurosis." The term "posttraumatic stress disorder" came into use in the 1970s in large part due to the diagnoses of U.S. military veterans of the Vietnam War. It was officially recognized by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980.

Symptoms may include disturbing thoughts, alterations in how a person thinks and feels, feelings or dreams related to the events, mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues, attempts to avoid trauma-related clues, and increase in the fight-or-flight response. Victims are at a higher risk for suicide.

In the earlier parts of World War I, victims of shell shock were sometimes executed as cowards or deserters.

surely held close in the hearts of his family

but not spoken of in the world

Was it shame? Or was it the intensity of the loss? How painful to have seen a young man off to war, then to receive back a man mentally shattered, and physically deteriorating. To have watched his mental and physical pain for years must have been very difficult. *culture issue, parents born in Germany? stalwart, very strong yet with heart, like Tillie?

herman's family, including his sister tillie brauer, who taught school until she was 80 years old

Herman was one of the seven children of Heinrich and Wilhelmena Brauer, born between 1875 and 1897. died in Justina Brauer Linnich died in 1956, John Brauer in 1899, Minnie Brauer in 1944, Ottilie Brauer in 1979, Henry Brauer in 1964, Herman Brauer in 1925, and Adeline Brauer McClintock (wife of Lester McClintock) in 1973. (One account says there were six children, probably omitting John, who died in 1899 at the age of 22.)

Herman's sister Ottilie was a teacher. She was known by adults as Tillie but by her many students as Miss Brauer. After teaching elsewhere for many years, she was the principle and also a teacher at Steinauer High School from 1944 to 1966. After that school closed, she taught high school math at Table Rock from 1967 to 1968. According to an article in the October 30, 1969 Argus about Tillie's retirment, "Miss Brauer planned to retire from teaching way back in 1944 after a teaching career in Idaho, Montana and Nebraska, but the acute teacher shortage prompted her to help out in the Steinauer school for the next 22 years, where she served as superintendent for much of that span. When the Steinauer school closed, she was asked to help out in math instruction in Table Rock, where she taught [until] finally retiring in 1968." She was born in 1888 and died in 1979 and was 91 when she died. She had been a teacher until she was 80 years old.

Larry Obrist, who had Miss Brauer all four years of high school, remembers and comments:

Herman's sister Ottilie was a teacher. She was known by adults as Tillie but by her many students as Miss Brauer. After teaching elsewhere for many years, she was the principle and also a teacher at Steinauer High School from 1944 to 1966. After that school closed, she taught high school math at Table Rock from 1967 to 1968. According to an article in the October 30, 1969 Argus about Tillie's retirment, "Miss Brauer planned to retire from teaching way back in 1944 after a teaching career in Idaho, Montana and Nebraska, but the acute teacher shortage prompted her to help out in the Steinauer school for the next 22 years, where she served as superintendent for much of that span. When the Steinauer school closed, she was asked to help out in math instruction in Table Rock, where she taught [until] finally retiring in 1968." She was born in 1888 and died in 1979 and was 91 when she died. She had been a teacher until she was 80 years old.

Larry Obrist, who had Miss Brauer all four years of high school, remembers and comments:

All my high school was with Miss Brauer and never heard his name mentioned. |

Note from the editor:

I knew Miss Brauer's classroom very well, too. She was my high school math teacher during her last years in Table Rock.

She was proud of being a teacher and would at times tell us that she was giving us a gift. I well remember tapping her chalk on the black board to get our firm attention -- tap tap tap -- "I want you to pay attention now," she said, "I am going to give you something that you can take with you. You will remember me someday when you are using this." Then explained fractions and some practical ways of thinking about them that I have used all my life.

Miss Brauer loved math, and she had a firm hand in writing on the black board.

She loved to tell stories. "The boys" in class -- Kim Binder, Richard Burgert, and Steve Cumro -- liked to distract her at the beginning of the class by probing her for stories of her past. "Miss Brauer, wasn't there somebody that something happened to on a hay rack ride?" And she would tell us the awful details along with a warning about how to avoid the same result. Then off they would get her going on another tack. She would abruptly take matters in hand, though. "Now you have got me off track again," she would say. "Let's get to work."

As Larry Obrist remembers, Miss Brauer never mentioned her brother Herman or his death. Amongst all the stories of happy times and sad, that family catastrophe she kept to herself.

Even had we known something about it, we wouldn't have expected her to share it. What an awful experience for the family. She would have been 30 years old when Herman went to the Great War and 37 years old at the time of his suicide and had been living elsewhere. Still.....

And what of her siblings who were still at home? They saw years of his suffering from shell shock and physical illnesses. They were there putting out the fire, watching him die of his gunshot wound and burns over the next several hours. And what of his mother? She was an invalid and could do nothing to help. She herself died later that same year. Herman died in March and Wilhelmina his mother died in December. (His father, Heinrich, had died before the war.) As a German family, the thought might be that they were simply stoic. However, as Larry points out, the horror and the shame would be too much for almost anybody. It is not something that one gets over. It is not something that just anybody talks about. This is sad in the case of Herman, as his life has been forgotten. He deserves to be remembered and honored. It is unimaginably what he and other American soldiers during the Great War went through, in the Marnes river valley and the Argonne Forest especially.

I knew Miss Brauer's classroom very well, too. She was my high school math teacher during her last years in Table Rock.

She was proud of being a teacher and would at times tell us that she was giving us a gift. I well remember tapping her chalk on the black board to get our firm attention -- tap tap tap -- "I want you to pay attention now," she said, "I am going to give you something that you can take with you. You will remember me someday when you are using this." Then explained fractions and some practical ways of thinking about them that I have used all my life.

Miss Brauer loved math, and she had a firm hand in writing on the black board.

She loved to tell stories. "The boys" in class -- Kim Binder, Richard Burgert, and Steve Cumro -- liked to distract her at the beginning of the class by probing her for stories of her past. "Miss Brauer, wasn't there somebody that something happened to on a hay rack ride?" And she would tell us the awful details along with a warning about how to avoid the same result. Then off they would get her going on another tack. She would abruptly take matters in hand, though. "Now you have got me off track again," she would say. "Let's get to work."

As Larry Obrist remembers, Miss Brauer never mentioned her brother Herman or his death. Amongst all the stories of happy times and sad, that family catastrophe she kept to herself.

Even had we known something about it, we wouldn't have expected her to share it. What an awful experience for the family. She would have been 30 years old when Herman went to the Great War and 37 years old at the time of his suicide and had been living elsewhere. Still.....

And what of her siblings who were still at home? They saw years of his suffering from shell shock and physical illnesses. They were there putting out the fire, watching him die of his gunshot wound and burns over the next several hours. And what of his mother? She was an invalid and could do nothing to help. She herself died later that same year. Herman died in March and Wilhelmina his mother died in December. (His father, Heinrich, had died before the war.) As a German family, the thought might be that they were simply stoic. However, as Larry points out, the horror and the shame would be too much for almost anybody. It is not something that one gets over. It is not something that just anybody talks about. This is sad in the case of Herman, as his life has been forgotten. He deserves to be remembered and honored. It is unimaginably what he and other American soldiers during the Great War went through, in the Marnes river valley and the Argonne Forest especially.

sources

NOTE: Some of the news articles give dates in 1918 for enlistment and for his arrival in France. However, it appears that this is almost certainly an error and has been changed above, although the original source document is below for examination. He likely enlisted in July 1917. Herman was in the 1st Division, which was originally the First Expeditionary Division, organized on June 8, 1917. Within a week, men were being shipped to the France; the last were sent in December 1917. In Herman's obituary and elsewhere, the reported dates were probably secured from the family and may have been affected by faulty reporting and/or by the fact that it had been about eight years earlier.

THE MARCH 25, 1925 PAWNEE CHIEF

To be scanned

THE MARCH 22, 1925 LINCOLN STAR:

OBITUARY IN THE MARCH 27, 1925 ARGUS

Herman Brauer, son of the late Henry ad Wilhelmina Brauer, was born June 14, 1883, and passed away March 21, 1925, at the age of 31 years and 9 months.

He was a member of the A.F.A.M. Lodge of Elk Creek and the I.O.O.F. Lodge No. 83 of Table Rock.

During the late war, he spent sixteen months in France, and was a member of the A.E.F., 1st Division,18 Inf., Co. A. He arrived in Germany December 1, 1918. He entered service on July 25, [1917], and served in three major and two minor engagements.

Besides his mother, brother Henry and sister, Minnie Brauer, he is survived by three other sisters, Miss Tillie Brauer of Central City, Mrs. Lester McClintock of near Pawnee City and Mrs. Lillich of Bird City, Kansas.

Funeral services were held last Monday morning at the home, conducted by Rev. Arthur Swanson, of the Methodist Church of Table Rock, while the American Legion Post of Pawnee City was present to pay the last tribute to their departed comrade.

Mrs. Edna Griffing sang "Somewhere the Sun is Shining."

The large delegation of the I.O.O.F. of Table Rock were present, from which organization the pallbearers had been selected.

Interment was made at the Table Rock Cemetery.

He was a member of the A.F.A.M. Lodge of Elk Creek and the I.O.O.F. Lodge No. 83 of Table Rock.

During the late war, he spent sixteen months in France, and was a member of the A.E.F., 1st Division,18 Inf., Co. A. He arrived in Germany December 1, 1918. He entered service on July 25, [1917], and served in three major and two minor engagements.

Besides his mother, brother Henry and sister, Minnie Brauer, he is survived by three other sisters, Miss Tillie Brauer of Central City, Mrs. Lester McClintock of near Pawnee City and Mrs. Lillich of Bird City, Kansas.

Funeral services were held last Monday morning at the home, conducted by Rev. Arthur Swanson, of the Methodist Church of Table Rock, while the American Legion Post of Pawnee City was present to pay the last tribute to their departed comrade.

Mrs. Edna Griffing sang "Somewhere the Sun is Shining."

The large delegation of the I.O.O.F. of Table Rock were present, from which organization the pallbearers had been selected.

Interment was made at the Table Rock Cemetery.