THE SCHOOLCHILDREN'S BLIZZARD OF 1888

From http://troytaylorbooks.blogspot.com/2013/01/thechildrens-blizzard-horroron-great.html?view=snapshot:

On this date, January 11, 1888, an unseasonably warm current of air moved out of the Caribbean and surged north into the American Great Plains. It was the first in a series of events – a perfect storm that would create a blizzard that would change the face of American history forever.

Early the following morning, a dark cloud appeared on the horizon. The air grew still for a long, eerie moment and then the sky began to roar and a wall of ice dust blasted the prairie. Every house, barn, fence row, wagon and living thing was instantly covered with shattered crystals, blinding, suffocating, smothering and burying anything exposed to the wind. The cold front raced across the open landscape, freezing everything in its path.

It swept across Montana first, and then buried North Dakota around the time that farmers were doing their early morning chores. South Dakota was frozen as children were finishing their morning recess at school and in Nebraska, school clocks were nearing the time for dismissal. In three minutes, temperatures in every region dropped more than 18 degrees. As night fell, the temperature kept dropping steadily, hour after hour, deluged by the cold from the northwest. The cold front brought snow, ice and subzero temperatures – and it also brought death.

By the morning of Friday, January 13, hundreds of people lay dead on the Dakota and Nebraska prairie, many of them children who had fled – or been sent home from – country schools at the same time the wind shifted and the sky was exploding.

It was a disaster created by bad luck and bad timing. The January blizzard – which has become known as the “Children’s Blizzard” or the “Schoolhouse Blizzard” – affected an entire region and its population. There was not a family among the farmers, settlers and town-dwellers on the prairie who was not personally affected by death caused by the storm, or who at least knew another family that was. It was a terrifying event and after it passed, the region was never the same again.

forward by the editorDo you remember learning in school about the Schoolchildren's Blizzard of 1888? I do. My 3rd grade teacher Alice Covault told it.

There was bad weather in January 1888, and then it became warm. Midwesterners did not know that a blizzard was sweeping down upon them. I ran across an account -- which I cannot now find -- that when it came, it was moved so fast and fierce that it ripped up the prairie sod and threw it in the air as it came forward. A Lincoln Journal-Star article on the 125th anniversary of the blizzard called it a "White Hurricane." Not only was the wind ferocious, but also the temperature had dropped to 40 degrees below zero. Sadly, children were still in school. Some teachers let their students go home, when the temperature first began to drop, but others r kept their children in the schools and tried to keep them warm. Of those, some tried to lead the children to safety. Some were successful, some not. |

an overview of the blizzardGet the big picture before reading about the Dopp family of Table Rock. Here is an excellent video, and the best essay I've ever seen on the subject.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

in table rock

the story of Avis Dopp

11 year-old in table rock caught in the open,

survived the schoolchildren's blizzard

|

Photograph 1000 - Avis Dopp is to the far left, the teacher in the dark dress. This is in front of the frame school building, built in 1874, which was used until a brick school was built in 1902. What age was she in this picture? Perhaps the blizzard was only ten years behind her? She was still identified as Avis Dopp, not Avis Taylor. We remember her as Mrs. Taylor, who lived to be 98 years old and was the mother of our grade school teacher Alice Taylor Covault, who herself lived to be be 98.

|

avis dopp's story recounted by glee covault.

Avis told Glee, and Glee tells schoolchildren each year, just as her mother-in-law Alice Covault once did.

Dick Taylor's article about the blizzard

I recently ran across a very nice local history on the website www.PawneeCountyHistory dot com. It is copyright 1991 by Dick Taylor and titled the Brash Blizzard of 1888. It describes the Dopp family's experiences, those of 11-year-old Avis and her father Seymour, a school teacher in Pawnee City.

I was astonished when I read this account, which focuses on the Dopp family. I am pretty sure that the person who made such an impression on my young mind was my teacher, Alice Taylor Covault. Dick Taylor's article describes the experiences of Alice's mother, Avis Dopp Taylor, who survived the blizzard at age 11.

As a kid, I delivered newspapers to Mrs. Taylor, probably the mid 1960s. I never connected her with history. She was elderly and I wished I could talk to her, but I was too shy. Here is a picture labeling Avis Dopp as the school teacher on the far left. I have found no picture of her father, Seymour Dopp, whose experiences are recounted in more than one article.

I was astonished when I read this account, which focuses on the Dopp family. I am pretty sure that the person who made such an impression on my young mind was my teacher, Alice Taylor Covault. Dick Taylor's article describes the experiences of Alice's mother, Avis Dopp Taylor, who survived the blizzard at age 11.

As a kid, I delivered newspapers to Mrs. Taylor, probably the mid 1960s. I never connected her with history. She was elderly and I wished I could talk to her, but I was too shy. Here is a picture labeling Avis Dopp as the school teacher on the far left. I have found no picture of her father, Seymour Dopp, whose experiences are recounted in more than one article.

more articles and stories about the blizzard

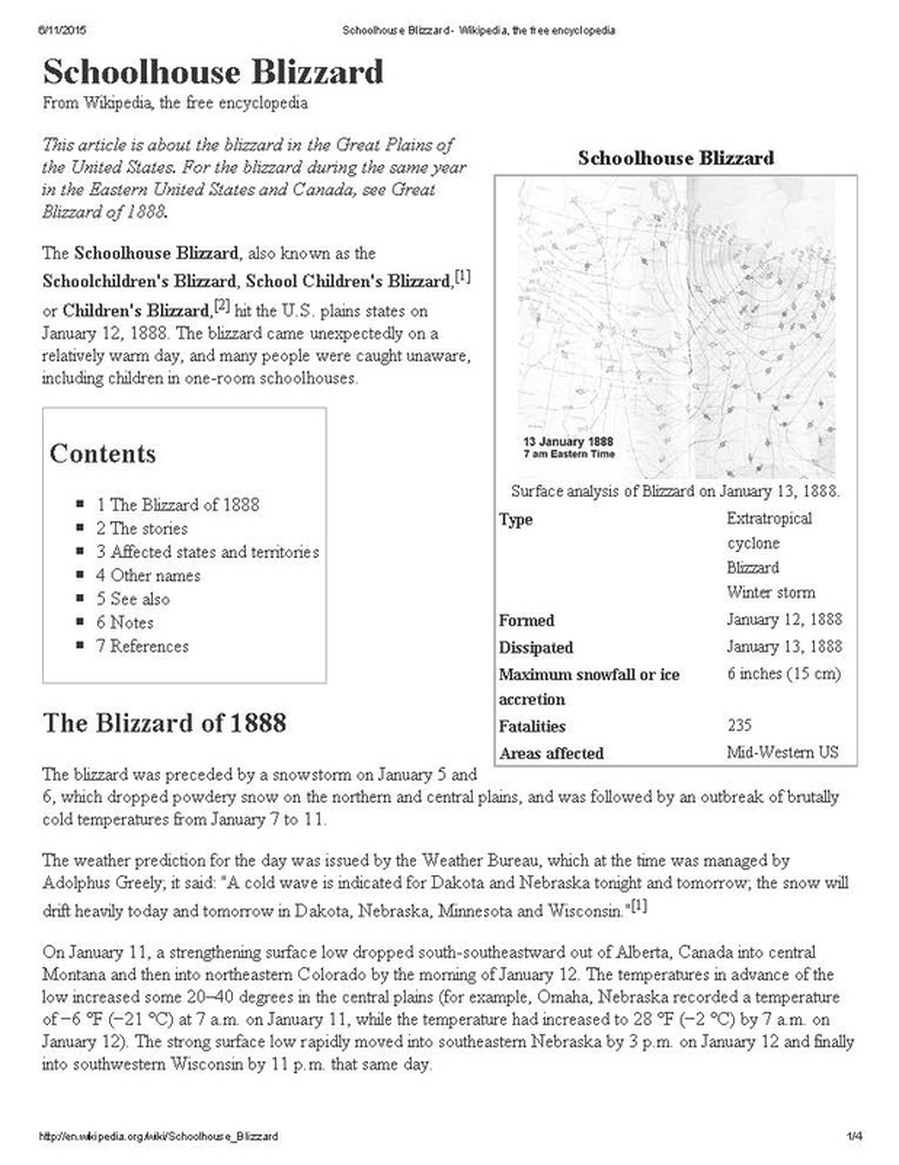

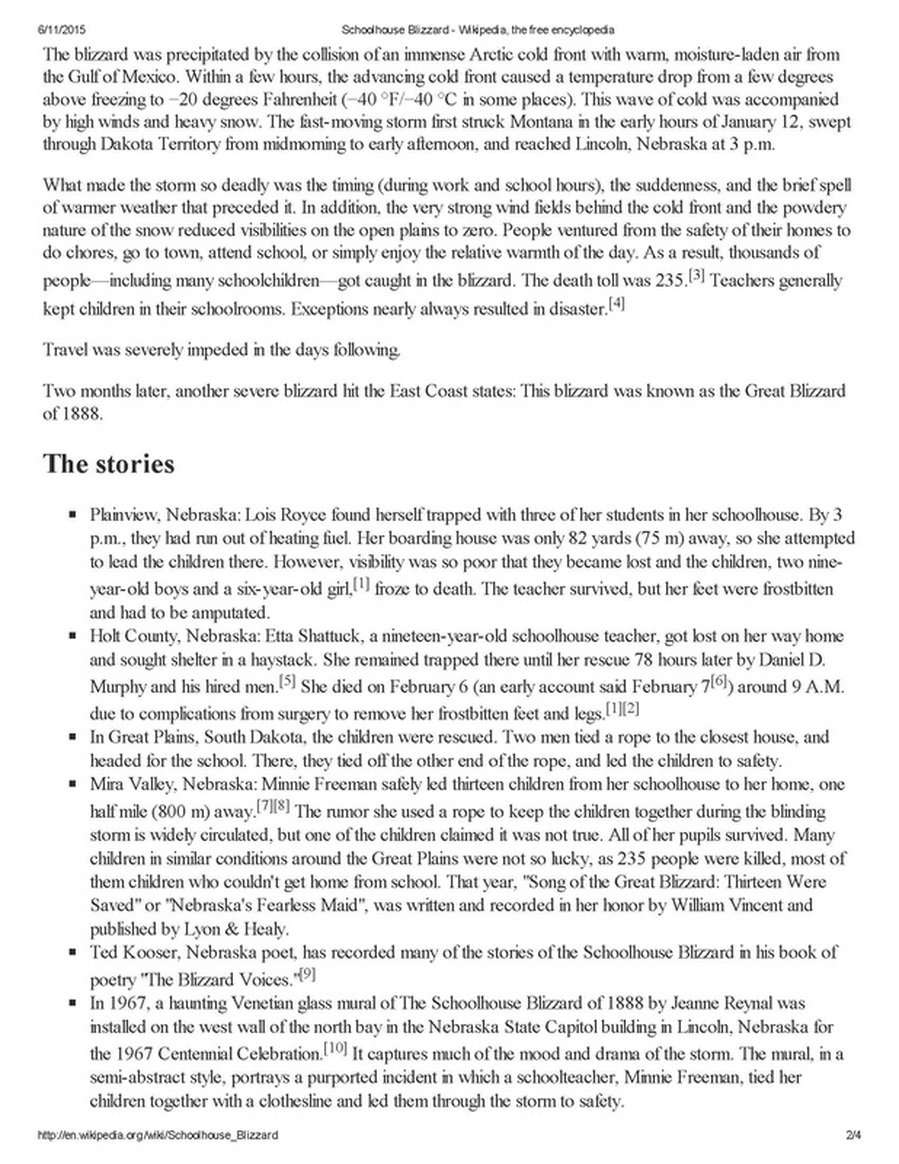

Wikipedia entry about the blizzard

For more technical details, check out the Wikipedia entry, inserted below: